Epidemiology and pathophysiology

At birth, there are adhesions between the prepuce and the glans of the penis. Over time these gradually break down. Mean age of 1st foreskin retraction is 10.4 years1. At 5 years 75% of boys have preputial adhesions, and by the age of 8, 8% have a physiological phimosis. By the age of 16, only 1% of phimosis persists2. Therefore, pathological phimosis should carefully differentiate from physiological phimosis.

Around 95% of pathological phimosis is due to the process ‘Balanitis xerotica obliterans’ (BXO); where keratinisation of the tip of the foreskin causes scaring and the prepuce remains non-retractile. Peak incidence for BXO is 9-11 years of age (75%)

Clinical Features

From history

Ballooning of the foreskin during micturition is a common presentation, but it is normal phenomenona non-retractile foreskin aged 2-4 years. This is self-resolving as the prepuce becomes more mobile with age and is not associated with obstructive uropathy.

BXO presents with scaring of the urethral meatus presents with irritation, dysuria, haematuria and local infection. If the meatus involved BXO or the prepucial scarring is very extensive, then the patient can present with episodes of urinary obstruction.

From examination

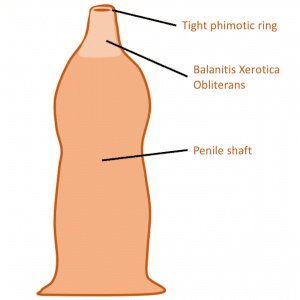

On examination, a BXO-affected prepuce will appear as a white, fibrotic and scarred preputial tip (Figure 1). It is normally difficult to visualise the meatus which can be similarly affected and scarred. In comparison, a physiological phimosis may non-retractile but will not have features of scarring and no meatal involvement.

Figure 1: A diagrammatic representation of BXO demonstrating a fibrotic and scarred preputial tip

Management

The mainstay of management of BXO is circumcision. It is important to send the foreskin off to histopathology in order to confirm the diagnosis.

Complications

Circumcision is a relatively simple procure and is done routinely as a day case procedure. Generally, dissolvable sutures are used to close the penile skin and these may be covered with a surgical glue. Topical antibiotics rather than oral tend to be prescribed.

Surgical complications from circumcision are primarily that of bleeding and infection. If there is significant bleeding, IV access should be obtained, a pressure dressing applied and the surgeon contacted urgently.

Post operatively expect a degree of swelling and some serous discharge around the penis for around a week post operatively. If there are still concerns about infection, this can be treated with antibiotics.

Untreated BXO can also lead to meatal stenosis, phimosis and erosions of glans and prepuce which can extended to the urethra.

.

References:

| 1 | Thorvaldsen MA, Meyhoff H. Phimosis: pathological or physiological. Ugeskr Læger. 2005 Apr 25;167(17):1858-62. |

| 2 |

Gairdner, D. (1949). The fate of the foreskin. A study of circumcision. Brit.med.J.,2,1433 |

Further reading:

Thomas DF, Duffy PG, Rickwood AM, editors. Essentials of paediatric urology. London: Informa Healthcare; 2008 May 19.

Heineman, E. “Pediatric surgery, springer surgery atlas series. P. Puri and M. Höllwarth

P. Godbole, Clinical Problems in Paediatric Urology 2008

Paediatric Surgery and Urology

First author: Dr David Thompson

Senior review: Mr Alex Cho