Introduction

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is a potentially blinding condition affecting the retina of preterm and low birth weight infants.

Epidemiology

ROP occurs in 60% of live births in which the birthweight (BW) is less than 1500g.¹ An incidence of 66-68% is reported in extremely preterm infants with a birthweight <1251g.² In 2020, there were 5015 live births with a BW less than 1500g in England and Wales, out of a total of 613,936 (0.8%).³ Of those identified to have ROP, less than 20% will reach stage 3 disease and 6% will require treatment.⁴

Pathophysiology

To understand why retinopathy of prematurity occurs, we must revisit the embryological development of the eye. The retina develops via the invagination of the optic vesicle, at the point of contact with surface ectoderm. The hyaloid artery enters the optic vesicle via the choroid fissure and the blood supply to the retina develops anteriorly, starting from the posterior aspect of the eye. The hyaloid artery will later become the central artery of the retina.⁵

Interruption to the normal development of vasculature supplying the retina in premature birth, plus the effects of hyperoxia leads to abnormal neovascular proliferation. This is largely due to the effect of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). The effect of abnormal vascularisation can cause detachment of the retina in severe cases of the disease. If full retinal detachment occurs, this is considered permanent blindness.

Risk Factors

The following are considered risk factors for ROP:

- Prematurity (<32 weeks gestation).

- Low birthweight (<1500g, significantly increased if <1250g).

- Uncontrolled hyper-oxygenation – previously common practise to give high-flow oxygen to premature infants to ensure adequate oxygenation however this was shown to cause ischaemic effects in retinal development and is considered the first stage in the development of ROP.

Clinical Features

There are limited clinical features which may be identified on bedside examination of a child with ROP. Therefore, the features of ROP are screened for in infants considered high risk using varying techniques under the guidance of a neonatal ophthalmologist.

Differential Diagnoses

Other causes of visual disturbance/impairment in neonates may be differentials for ROP.

Cataracts:

- Rubella/Measles/Other infections

- Use of tetracyclines during pregnancy

- Inherited metabolic conditions

- Diabetes

Infection:

- Conjunctivitis

- Malignancy

- Retinoblastoma (Rare)

Investigations

Screening

All infants less than 31 weeks’ gestational age (GA) or less than 1501g birth weight (BW) should be examined to screen for presence of ROP.⁶

First examination:⁶

Infants born before 31+0 weeks GA should be screened between 31+0 and 31+6 post-menstrual age (PMA) or at 4 weeks post-natal age (PNA), whichever is later.

Infants born from 31+0 GA should be screened at 36 weeks PMA or 4 weeks PNA, whichever is sooner.

Zones:

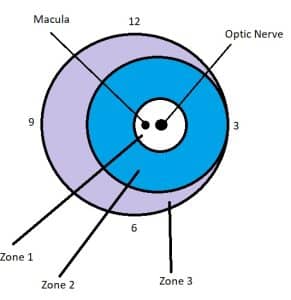

The posterior eye is divided into 3 zones. Zone 1 is the smallest and most central area surrounding the optic disc. Zones 2 and 3 are extensions of this moving, further from the optic disc. The location of ROP has a significant prognostic indication as Zone 1 lesions will condemn the wider aspects of the retina due to the nature of retinal blood supply.

Figure 1: Diagram showing zones of the retina of the right eye. In practice a standard diagram would contain demarcation of the zones of both eyes, with clock numbers to assist in description of location of lesions/abnormalities.

Pathology Staging:

- Stages 1-3 describe evidence of ROP lesion varying from thin demarcation line to extensive neovascularisation.

- Stages 4 and 5 describe retinal detachment as partial or total, respectively.

- Pre/Plus disease- This is a term used to differentiate severity of vascular dilation and tortuosity.

Referral for treatment:

Referral for treatment should be made if any of the following criteria are met:

- Zone 1 with plus disease and any stage ROP.

- Zone 1 without plus disease but with stage 3 ROP.

- Zone 2 with plus disease (in at least 2 quadrants) and with stage 3 ROP.

Ongoing screening:

If no treatment is required, screening should continue, and take place either every week or every two weeks.

Criteria for the termination of screening include:

- Without ROP = when vascularisation has extended into zone 3 (likely before 36 weeks PMA)

- With ROP = partial resolution progressing towards complete resolution; change in colour of ridge from salmon pink to white; growth of vessels through the demarcation line.

Management

As described above, ROP can be divided into stages. These stages determine the frequency ofscreening and provide the indications for intervention. There are two mainstays of treatment:

Laser therapy:

Successfully reverses ROP in 90% cases.⁷ Involves use of laser to “burn” abnormal areas of the retina in which there is inadequate vascularisation. This burning process prevents abnormal blood vessel proliferation. 1 in 10 infants treated with laser-therapy will require repeat treatment 2-3 weeks after the initial treatment.

Anti-VEGF:

In some cases in which either laser-therapy has been unsuccessful and/or the ophthalmologist deems it an appropriate early treatment option, the eye receives an injection of anti-VEGF solution. This blocks the action of VEGF and effectively stops ongoing abnormal proliferation. 1 in 3 infants will require repeat anti-VEGF treatment 3-4 months after initial treatment.

Complications

After treatment there is a 1 in 100 chance of infection, cataract formation or retinal detachment.

80% of severe ROP cases will go on to have good or very good eyesight.

Children who are diagnosed with ROP are more likely to be short-sighted and develop a squint.

References

| No. | Reference |

| 1 | Zin A., Gole G.A. Retinopathy of prematurity-incidence today. Clinics in Perinatology 2013; 40(2): 185-200 |

| 2 | Cryotherapy for Retinopathy of Prematurity Cooperative Group. The Natural Ocular Outcome of Premature Birth and Retinopathy: Status at 1 Year. Archives of Ophthalmology 1994; 112(7): 903-912 |

| 3 | Office for National Statistics. Birth Characteristics: Live births by birthweight and area of usual residence 2020, January 2022. Retrieved from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/livebirths/datasets/birthcharacteristicsinenglandandwales |

| 4 | Sadler TW. Langman’s medical embryology. 12th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2012. p. 329 – 338 |

| 5 | Palmer E.A., Flynn J.T., Hardy R.J., et al. Incidence and early course of retinopathy of prematurity. Ophthalmology 1991; 98(11): 1628-1640 |

| 6 | Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. UK screening of retinopathy of prematurity guideline: Summary of recommendations, March 2022 |

| 7 | Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Information Leaflet for Parents/Guardians: Treatment for Retinopathy of Prematurity (ROP), August 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/ROP_Information_Leaflet.pdf |