Hirschsprung’s disease (HD), also known as congenital aganglionic megacolon disease, is a congenital disease in which ganglionic cells fail to develop in the large intestine. This commonly presents as delayed or failed passage of meconium around birth.

Epidemiology

The international incidence of Hirschprung disease is believed to be 1 case per 1,500-1,700 (1). Around 90% of these present in the neonatal period, with the median age of presentation at 2 days. The most common clinical feature at presentation is abdominal distension and bilious vomiting with failure to pass meconium (2).

Males have a higher incidence to female, and the male: female ratio is estimated to be 4:1(3). There are several genes that are believed to be involved. The main genes that are associated with the disease are those that encode the proteins for the RET signaling pathway and endothelin type B receptor pathway. The strongest association with Hirschsprung’s, is the Receptor tyrosine kinase (RET) gene, a proto-oncogene on chromosome 10q11. HD is strongly associated with chromosomal abnormalities, with 10-15% HD cases associated with trisomy 21 (Down Syndrome).

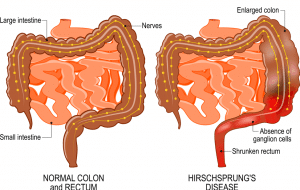

There are three main subtypes of Hirschsprung’s disease, which are short-segment, long-segment, and total colonic aganglionosis disease. The short segment is the most common, consisting of 85% of cases, where the aganglionosis is restricted to the rectosigmoid portion of the colon (figure 1). The long-segment disease is significantly less common, making up 10% of the cases, where the aganglionosis extends past the rectosigmoid portion of the colon to the splenic flexure. Rarely, there’s total colonic aganglionosis, where the entire colon is affected, which tends to be the severest form of the disease. Even rarer, the distal small bowel is affected, and this is associated with a high mortality and morbidity (1).

Pathophysiology

Hischsprung’s disease is where ganglionic cells of the myenteric and submucosal plexuses in the bowel aren’t present proximally from the anus to a variable length along the large intestine. The enteric nervous system is derived from the vagal segment of neural crest cells which migrate along the vagus nerve to enter the foregut mesenchyme in a cranial to caudal direction. The most common accepted aetiology of this disease is due to the arrest of the neuroblast, derived from neural crest cell migration in fetal development between week 8 to 12. It is also accepted that sometimes normal cell migration occurs but the neuroblast fails to properly develop due to apoptosis, improper differentiation, or failure in proliferation (4).

The aganglionic segment remains in a tonic state leading to failure in peristalsis and bowel movements. Faeces in the rectum fail to trigger relaxation of the internal anal sphincter, due to aganglionosis. The accumulation of faeces in the rectosigmoid region is responsible for the functional obstruction, which is the cause of many of the symptoms. It can lead to proximal bowel dilatation which can present as abdominal distension. Increased intraluminal pressure can lead to decreased blood flow and deterioration in the mucosal layer. This stasis can lead to bacterial proliferation and the subsequent complication of Hirschsprung’s enterocolitis, which has a mortality rate of 25-30%. If not recognised early this can lead to sepsis and death (1).

Risk Factors

Risk factors include (3):

- Males: The male to female ratio is approximately 4:1

- Chromosomal abnormalities: It’s associated with several chromosomal abnormalities, the most prominent of which is Down Syndrome.

- Family History: It’s a complex form of inheritance, that’s often due to mutations in the RETproto-oncogene on chromosome 10q11. The majority of cases are genetically sporadic, although 20% of cases are familial and can be either dominant or recessive (5).

Clinical Features

Classically this disease presents as failure to pass meconium within 48 hours of birth. Yet a recent study in the UK and Ireland cautioned against overly relying on this symptom, as it was only present in approximately 26% of the cases. Other common clinical features are abdominal distension and bilious vomiting. The classic triad of abdominal distension, bilious vomiting, and failure to pass meconium is present in around 25% of Hirschsprung patients (2).

Failure to pass faeces leads to dilation of the proximal bowel. The faecal mass can be palpated in the left lower abdomen. The abdomen is sometimes tympanic due to the intestinal distension.

Rectal examination commonly reveals an empty rectal vault and can result in the forceful discharge of gas and faecal material (3).

Classical presentation

25% of patients have the classical triad of:

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses include (5):

- Meconium Plug Syndrome: Leads to failure to pass meconium but symptoms should resolve after passage of plug. Can be differentiated by barium enema or water-soluble contrast enema (water soluble preferred as less risk of perforation)

- Meconium Ileus: Distal small bowel is impacted by meconium leading to abdominal distension and failure to pass meconium.Can be differentiated by radiograph, barium enema or water-soluble contrast enema.

- Intestinal atresia: Congenital malformation of any part of the intestine resulting in complete obstruction. The presentation will depend on the site of the blockage but will usually involve abdominal distension and failure to pass meconium.

- Intestinal malrotation: This is caused by a congenital anomaly in the rotation of the midgut during embryological development. This can result in midgut volvulus presenting with bilious vomiting and abdominal distension.

- Anorectal malformation (anal stenosis, imperforate anus): Congenital abnormalities in development of the lower colon can present with failure to pass meconium and abdominal distension. Can be differentiated by physical examination of the rectum that reveals malformation.

- Constipation:Difficulty in passing stools. This is a diagnosis of exclusion.

Investigations

Initial investigation is imaging with a plain abdominal radiograph.

A contrast enema would be considered based on the clinical situation of the neonate to aid with diagnosis and exclusion of the aforementioned differentials, though imaging alone is not diagnostic. A contrast is also useful to determine the transition zone in HD and the extent of aganglionosis that will be resected in surgery. An absolute contra-indication to a contrast enema would be the presence of perforation, in which case a laparotomy would be performed.

The classic finding on contrast is a short transition zone between the proximal end of the colon and the narrow distal end of colon (see: https://radiopaedia.org/cases/hirschsprung-disease?lang=us). A rectal diameter similar or equal to the sigmoid colon is also highly suggestive of Hirschsprung’s disease (5).

The gold standard for diagnosis is a rectal suction biopsy, as the submucosa needs to be tested for ganglionic cells. This is a simple bedside procedure with a high degree of accuracy and without the risks associated with general anaesthetic (6). It is important to give adequate antibiotic coverage around the procedure and provide good decompression of the bowel as washouts cannot be performed for 24 hours after the procedure.

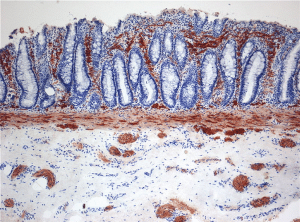

The biopsy is stained for acetylcholinesterase to aid in interpretation, although calretinin staining is increasingly used as an adjunct. It should confirm aganglionosis, no ganglion cell in both the submucosal and myenteric plexus, with several hypertrophied nerve bundles that stain positive for acetylcholinesterase (figure 2). There is an associated risk of perforation, bleeding, and inadequate sample which would necessitate re-biopsy.

Figure 2: Histopathology of Hirschsprung’s Disease also known as aganglionosis. Enzyme histochemistry showing aberrant acetylcholine esterase (AChE)-positive fibres (brown) in the lamina propria mucosae.

Rectal Suction Biopsy Guidelines

Although it’s the gold standard for diagnosis, NICE guidelines suggest that rectal suction biopsy should be avoided unless the following clinical features are present (7):

- Delayed passage of meconium (more than 48 hours after birth in term babies)

- Constipation since first few weeks of life

- Chronic abdominal distension plus vomiting

- Family history of Hirschsprung’s disease

- Faltering growth in addition to any of the previous features.

Management

Initial management would involve IV antibiotics, nasogastric tube insertion and bowel decompression. Liaising with the local paediatric surgeons for early consideration of the above investigations is important to consider (4).

The only definitive treatment is surgery, and the three main surgical procedures are the Swenson, Soave, and Duhamel pull-through procedures (4). The details of these are beyond the scope of this article but they are usually performed in the first few months of the neonate’s life (4). All involve resecting the aganglionic section of bowel and connecting the unaffected bowel to the dentate line (or just above the dentate line in the pull-through) (4).

Complications

Hirschsprung associated enterocolitis (HAEC) is the main cause of mortality of patients with Hirschsprung’s disease. Stasis of faeces leads to bacterial overgrowth, particularly of Clostridium difficile, Staphylococcus aureus, and anaerobes, within the colon. This often presents as fever, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal tenderness, and eventually sepsis if not recognized early enough. The emergency treatment for suspected enterocolitis is with fluid resuscitation, bowel decompression and broad-spectrum IV antibiotics (1). This presentation would also warrant stool culture and abdominal x-ray.

Enterocolitis is an uncommon but serious complication of surgery. Approximately 25-30% of postoperative patients develop HAEC, usually within the first year after surgery. Long-segment and total colonic aganglionosis Hirschsprung disease are at a higher risk of developing enterocolitis. After surgery, prophylactic antibiotics and colon irrigations can be initiated to help prevent HAEC (4).

The possible complications of the surgery are constipation, enterocolitis, perianal abscess, faecal soiling and adhesions. An estimated 10% will require further surgery to treat constipation and incontinence.

Prognosis

Long term prognosis is generally positive, with many patients acquiring faecal continence. Outcome is usually dependent on the extent of aganglionosis with longer sections correlating with increasing complications.

References

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence(2010). Constipation in children and young people: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline (CG99); Available at: [https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg99]. Accessed 10/10/2017.

- Kliegman, R. (2015) Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics E-Book : Expert Consult. 20th ed.. edn. Saint Louis: Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Hirschsprung disease. Available at: http://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/OC_Exp.php?lng=EN&Expert=388. Accessed: 8/22/2017.

- Wagner P, Justin, “Hirschsprung Disease”, May 2017. Available at: [http://emedicine.staging.medscape.com/article/961963-differential] Accessed 10/10/2017.

- Chhabra, S. and Kenny, S.E. (2016) ‘Hirschsprung’s disease’, Surgery (Oxford), vol. 34, no. 12, pp. 628-632,2016.

- Bradnock, T.J., Knight, M., Kenny, S., Nair, M. and Walker, G.M. ‘Hirschsprung’s disease in the UK and Ireland: incidence and anomalies’, Archives of Disease in Childhood, vol. 102,no.8, pp. 722,2017.

- Rahman Z, Hannan J, Islam S. Hirschsprung’s disease: Role of rectal suction biopsy-data on 216 specimens. Journal of Indian Association of Pediatric Surgeons. 2010 Apr;15(2):56.

- Kliegman, R. (2015) Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics E-Book : Expert Consult. 20th ed.. edn. Saint Louis: Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Bradnock, T.J., Knight, M., Kenny, S., Nair, M. and Walker, G.M. ‘Hirschsprung’s disease in the UK and Ireland: incidence and anomalies’, Archives of Disease in Childhood, vol. 102,no.8, pp. 722,2017.

- Hirschsprung disease. Available at: http://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/OC_Exp.php?lng=EN&Expert=388. Accessed: 8/22/2017.

- Chhabra, S. and Kenny, S.E. (2016) ‘Hirschsprung’s disease’, Surgery (Oxford), vol. 34, no. 12, pp. 628-632,2016.

- Wagner P, Justin, “Hirschsprung Disease”, May 2017. Available at: [http://emedicine.staging.medscape.com/article/961963-differential] Accessed 10/10/2017.

- Rahman Z, Hannan J, Islam S. Hirschsprung’s disease: Role of rectal suction biopsy-data on 216 specimens. Journal of Indian Association of Pediatric Surgeons. 2010 Apr;15(2):56.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence(2010). Constipation in children and young people: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline (CG99); Available at: [https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg99]. Accessed 10/10/2017.