Introduction

Necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) is among the most common neonatal surgical emergencies1 and has significant morbidity and mortality. 2 It is characterised by variable injury to the intestines, ranging from mucosal damage to necrosis and perforation. 3

Epidemiology

The incidence of NEC is 1-3/1000 live births. This increases to 5-10% in very low birth weight (VLBW) infants.1 90% of cases occur in preterm infants, while the incidence is reduced 6-fold in breastfed infants.1 The mortality rate associated with NEC is estimated to be between 20-30% depending on severity.4 Complications occur post-surgery in about 27% of infants with surgical NEC, while about 3% are discharged before 28-days post-decision to intervene surgically.8

Pathophysiology

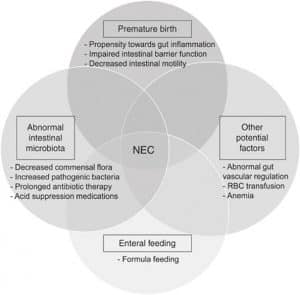

The pathophysiology of NEC is yet to be understood entirely. Still, it is likely due to an innate immune response to the microbiota of the premature infant’s gut, thereby leading to inflammation and injury.5 Genetic predisposition and microvascular tone imbalance have also been suggested to be contributing factors.4

Risk factors1

- Prematurity or very low birth weight (VLBW)

- Formula feeding

- Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR)

- Polycythaemia

- Exchange transfusion

- Hypoxia

Clinical Features

The classic presentation of NEC includes feeding intolerance, vomiting (may be bile or blood-stained), abdominal distention and haematochezia.2,3 As NEC progresses, features include abdominal tenderness, abdominal oedema, erythema and palpable bowel loops (due to loop dilation).

In addition to gastrointestinal features, NEC also presents with systemic features such as apnoea, lethargy, bradycardia and decreased peripheral perfusion.3

Differential diagnosis

Due to the non-specific presentation of NEC, its differential diagnosis is broad. Differentials to consider include:

- Neonatal sepsis

- Hirschsprung disease

- Intestinal malrotation

- Intestinal volvulus

- Gastroesophageal reflux

- Spontaneous intestinal perforation

- Infectious enterocolitis3

Investigations

Imaging

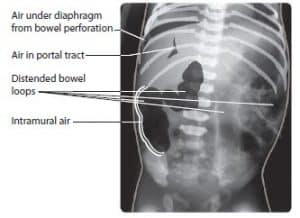

Plain abdominal radiography is the diagnostic imaging for NEC. Features include distended bowel loops, thickened bowel wall (bowel oedema), intramural gas (pneumatosis intestinalis), gas in the portal tract and pneumoperitoneum in the later stages due to bowel perforation.3,4

Laboratory tests

- Full blood count- anaemia, thrombocytopenia and leukocytosis/leukopenia are often present.

- U & Es- hyponatraemia

- Blood gas- metabolic acidosis

- Blood culture- to rule out sepsis

Staging

NEC is staged according to the Bell scoring system based on clinical features and abdominal x-ray features:1,6

| Bell’s Stage | Severity | Clinical features | Radiological features |

| Stage I | Suspected NEC | Systemic: Lethargy, temperature instability, apnoea, bradycardia.

Intestinal: Emesis, abdominal distension, haematochezia

|

Bowel distension only. |

| Stage II | Definite NEC | As in Stage I plus:

Systemic: metabolic acidosis, thrombocytopenia

Intestinal: abdominal tenderness, absent bowel signs

|

Bowel distension

Portal venous gas Pneumatosis intestinalis |

| Stage III | Advanced NEC | As in Stage I and II plus:

Systemic: severe acidosis, electrolyte abnormalities, thrombocytopenia, DIC.

Intestinal: Marked GI bleeding

|

As in Stage II plus pneumoperitoneum |

Management

Prophylaxis

NEC can be prevented by administering antenatal steroids if premature delivery is anticipated.1 Breastfeeding is a protective factor.1 Research has also shown that probiotics reduce the risk of NEC.1

Medical Management

Suitable for most infants with Bell Stage I and Stage II NEC and includes the following:

- Withhold oral feeds for 10-14 days and replace with parenteral nutrition.

- IV antibiotics for 10-14 days based on local protocols.

- Systemic support in the form of ventilatory support, fluid resuscitation, inotropic support, correction of acid-base balance coagulopathy and/or thrombocytopenia.1,7

Surgical Management

Indications for surgery for NEC include:

- Intestinal perforation

- GI obstruction secondary to stricture formation

- Deterioration despite medical management1,7

Different surgical methods exist for NEC management depending on the extent of the disease. The most common procedure carried out for NEC is intestinal resection with stoma formation.8 Other procedures include resection with primary anastomosis, stoma formation without resection, clip and drop with resection, open and close laparotomy and negative initial laparotomy.8 The need to perform a clip and drop procedure is associated with increased 28-day mortality.8 Some infants undergo peritoneal drainage, but most subsequently require laparotomy.8

Complications

Immediate complications of NEC include intestinal perforation, sepsis and death. 50% of patients that survive NEC develop long-term complications.3 The most common long-term complications are intestinal stricture and short-bowel syndrome.3 Other long-term complications include neurodevelopmental disorders and NEC recurrence.3

References

| No. | Reference |

| 1 | Tasker RC, McCLure RJ, Acerini CL. Oxford handbook of paediatrics. 2nd ed. England: Oxford University Press; 2013.

|

| 2 | Lissauer T. Illustrated textbook of paediatrics. 5th ed. London: Elsevier Science; 2018. 176 p.

|

| 3 | Springer SC, Annibal DJ. Necrotizing Enterocolitis. [Internet] [Updated 2017 Dec 27]. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/977956-overview

|

| 4 | Neu J, Walker WA. Necrotizing enterocolitis. The New England journal of medicine. [Internet] 2011; 364(3): 255–264. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1005408

|

| 5 | Tanner SM, Berryhill TF, Ellenburg JL, Jilling T, Cleveland DS, Lorenz RG, Martin CA. Pathogenesis of necrotising enterocolitis: modeling the innate immune response. The American journal of pathology [Internet] 2015; 185(1): 4–16. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.08.028

|

| 6 | Sheik Y, Gaillard, F. Necrotising enterocolitis (staging). [Internet] Available from: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/necrotising-enterocolitis-staging-1

|

| 7 | Zani A, Pierro A. Necrotising enterocolitis: controversies and challenges. F1000 Research [Internet] 2015; 4. Available from: https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.6888.1

|

| 8 | Patel RM, Denning PW. Intestinal microbiota and its relationship with necrotizing enterocolitis. Paediatric research [Internet] 2015; 78: 232-238. Available from https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2015.97

|