Introduction

Atopic eczema, also known as atopic dermatitis, is a chronic inflammatory skin condition seen in children. It causes dry, scaly, and itchy red skin often starting on the face and scalp.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of childhood eczema has increased greatly in the past 50 years, now affecting around 1 in every 5 children in the UK. Males and females are affected equally. About 80% of eczema cases start before the age of 5 years.1 The majority of cases often develop during infancy.

Pathophysiology

Environmental, genetic, and immunologic factors, among others, contribute to an impaired skin barrier and dysregulated immune system.

The pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis is not fully understood. One proposed cause is a mutation of the FLG gene which encodes the protein filaggrin. Filaggrin makes up part of the stratum corneum of the epidermal barrier.2 This barrier is crucial in restricting water loss, and preventing the unwanted entry of irritants, allergens, and skin pathogens.

Therefore, impairment of the epidermis can allow: 2

- Environmental allergen penetration through the skin, causing hyper-reactivity and systemic IgE sensitisation (type 1 hypersensitivity reaction).

- Entry of pathogens.

- Water loss, resulting in dryness.

It is also suggested that those with more T-helper 2 cells (rather than T-helper 1), have a higher production of IgE and increased mast cell hyper-reactivity. This contributes to increased inflammation and pruritus.2

Common trigger factors:3

- Irritant allergens e.g. soaps and detergents

- Irritant clothing e.g. synthetic fabrics

- Skin infections e.g. Staphylococcus aureus

- Contact allergens e.g. in perfumes

- Inhalant allergens e.g. pets and pollen

- Hormonal triggers

- Climate

- Teethin

- Stress

- Dietary history e.g. milk, egg, wheat

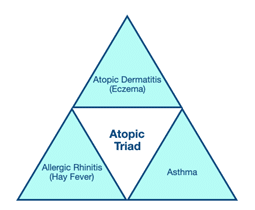

Atopic Triad

The term ‘atopic’ describes a genetic disposition for over-activity of the immune system in response to environmental factors.4 The atopic triad are atopic dermatitis (eczema), allergic rhinitis (hay fever) and asthma, which are often seen together.5 If a patient has one of these conditions, it is important to ask about the other two when considering their past medical history.

Figure 1: Atopic triad of atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis and asthma.

History3

- Time of onset, pattern, and severity

- Itchiness (pruritus) and scratchin

- Possible trigger factors – irritant and allergic

- Dietary history

- Tiredness and irritability (poor quality sleep is contributory)

- Response to previous and current treatments

- Family or personal history of atopic triad – atopic eczema, allergic rhinitis, and asthma

- History of recurrent rash before age of 2 years

- Social history – impact of symptoms on children and their parents/carers

Examination

Common signs:3

- Erythema

- Dry skin

- Bleeding

- Water blisters around the hands and feet

Infants

Infants are generally affected around the scalp, face, and flexures. Hair loss may be noticed where the infant has excessively rubbed their skin.6

Figure 2: Inflamed atopic dermatitis around the scalp and face of a 2-month-old child.

Toddlers and school-age children

With increasing age, the distribution of childhood eczema changes. Usually, the distribution becomes flexural, and eczema can also be noticed around the mouth and chin due to dribbling or eating. Excessive scratching or rubbing can cause the skin to thicken (lichenification).6 Lichenification is evidence of long-standing, poorly controlled eczema.

Common Patterns of atopic eczema in children:

- Flexural – creases at the elbows, knees, wrists and neck

- Discoid – coin-sized areas of inflammation on the limbs

- Follicular – small circular bumps around hair follicles

Discoid and follicular distributions are more common in Asian, Black Caribbean and Black African children.

Differential diagnosis

There are several conditions which may present similarly to atopic eczema, but there are often differentiating features which are helpful to learn. 3

| Differential Diagnosis | Differentiating Features |

| Psoriasis

|

|

| Allergic contact dermatitis

|

|

| Seborrhoeic dermatitis

|

|

| Fungal infection

|

|

| Scabies

|

|

Diagnosis

There are no laboratory tests or imaging required to diagnose atopic eczema. It is a clinical diagnosis based on history and examination.

It is likely if the following criteria are met: 3

- Visible flexural eczema involving the skin creases (cheeks and/or extensor areas in children <18 months)

- Personal history of flexural eczema (cheeks and/or extensor areas in children <18 months)

- Personal history of dry skin in the last 12 months

- Personal history of asthma/allergic rhinitis (or atopic disease in a first-degree relative of a child under 4 years)

- Onset before 2 years old (if currently over 4 years of age)

Management

Eczema cannot be cured, but it can be managed. Management is stepwise depending on severity which is classified by: 3

| Mild | Moderate | Severe |

|

|

|

Daily care

- Daily bathing with emollients. Do not use soap or shampoo

- Daily use of fragrance-free and alcohol-free moisturisers/emollients (e.g., Aveeno, Dermol 500, Cetraben).

- Avoid skin trauma – keep fingernails short, use of mittens to prevent scratching

- Preventative treatment

- Maintenance regimen of topical corticosteroids to reduce the frequency of flares

- Topical calcineurin inhibitors (e.g., tacrolimus) – requires specialist care

- Education – children and their parents should be educated on how to recognise and manage flares of atopic eczema. Offer information leaflets on application of emollients, and management of flares

- Regularly review emollient, topical corticosteroid and non-sedating antihistamine use

Management of flares

Eczema flares should be treated immediately until approximately 48 hours after the symptoms lessen. For all severities of eczema, emollients will be prescribed to be used for bathing, and generous moisturising. 3

| Mild | Moderate | Severe |

|

|

|

Complications

Infection

- Bacterial infection with Staphylococcus aureus can cause increased redness, oozing and crusting of the skin. This is managed with oral antibiotics or intravenous if systemically unwell.

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection presents as grouped vesicles and punched-out erosions. Disseminated HSV infection, called eczema herpeticum, involves widespread lesions that can combine to extend across the entire body. This is a medical emergency which can be accompanied by fever, lymphadenopathy, and malaise, and can lead to hepatitis and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).3 Treatment is with an oral or intravenous antiviral (aciclovir) agent.

Psychosocial problems

Poorly controlled eczema can largely impact a child’s quality of life and psychosocial wellbeing by affecting their ability to carry out everyday activities, and disrupting sleep. This also negatively impacts on the lives of siblings and parents.

Depression, social restrictions, and low self-confidence are reportedly higher amongst children and young people with eczema.

It is therefore important that healthcare professionals take a holistic approach to deciding treatment options and providing the relevant advice.7

Follow up

Mild eczema: can be managed in primary care (General Practitioner).

Moderate to severe eczema: referred to secondary care or dermatology team if recurrent flares and/or suboptimal response to daily care.

Prognosis

Throughout childhood, eczema generally presents episodically with flares occurring two or three times a month. Often the condition improves with time, but for some children it can continue or worsen later in life.

Approximately one third of children with eczema will develop asthma and/or hay fever in the future. This is known as the atopic march.5

References

| No. | Reference |

| 1 | Williams HC, Wüthrich B. The natural history of atopic dermatitis. In: Williams HC, editor. Atopic Dermatitis: The Epidemiology, Causes and Prevention of Atopic Eczema. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000:41–59. |

| 2 | Eczema – atopic | Health topics A to Z | CKS | NICE [Internet]. NICE 2021, [cited 9 March 2021]. Available from: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/eczema-atopic/ |

| 3 | Nutten S. Atopic Dermatitis: Global Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism. 2015;66(Suppl. 1):8-16. |

| 4 | Atopic Eczema – BAD Patient Hub [Internet]. BAD Patient Hub. 2021 [cited 9 March 2021]. Available from: https://www.skinhealthinfo.org.uk/condition/atopic-eczema/ |

| 5 | Spergel J. From atopic dermatitis to asthma: the atopic march. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 2010;105(2):99-106. |

| 6 | Atopic dermatitis | DermNet NZ [Internet]. Dermnetnz.org. 2021 [assessed 15 June 2021]. Available from: https://www.dermnetnz.org/topics/atopic-dermatitis/ |

| 7 | Guidance | Atopic eczema in under 12s: diagnosis and management | Guidance | NICE [Internet]. NICE 2021 [cited 9 March 2021]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG57/chapter/1-Guidance#diagnosis |