Introduction

Central Nervous System (CNS) tumours are the most common tumours that develop in children, and account for around 20% of childhood cancer each year. A tumour in the brain can originate from the brain itself (primary) or spread from other parts of the body (secondary). This article aims to describe primary brain tumours1.

Epidemiology

Brain tumours affect around 400 young people per year in the UK, with 10 children and teenagers being diagnosed with a brain tumour every week. Boys are slightly more commonly affected than girls1.

Pathophysiology

The precise cause of primary CNS malignancy is unknown; however the most likely cause is due to a combination of genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors.

There are over 130 different types of tumour from within the CNS. They are typically named after the type of cell they develop from but can be named in relation to where in the CNS they develop.

The most common groups of brain tumours in children are2,7:

- Astrocytoma (low and high grade gliomas that develop from glial cells) [40%]

- Medulloblastoma (usually develop in the posterior fossa/cerebellum) [13%]

- Ependymoma (formed from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) producing ependymal cells) [7%]

- Craniopharyngioma (found at the base of the brain close to the pituitary gland) [5%]

- Germ cell tumours (arising from germ cells, usually found close to the pituitary gland and the pineal gland) [4%]

- Choroid plexus tumours (develop from network of ependymal cells) [2%]

Risk Factors

There are a range of risk factors associated with CNS malignancies. The following are all associated with an increased risk of childhood brain tumours3:

- Personal or family history of a brain tumour, leukaemia, sarcoma, and early onset breast cancer

- Prior therapeutic CNS irradiation

- Neurofibromatosis 1 and 2

- Tuberous sclerosis 1 and 2

- Other familial genetic syndromes (such as von Hippel-Lindau)

Clinical Features

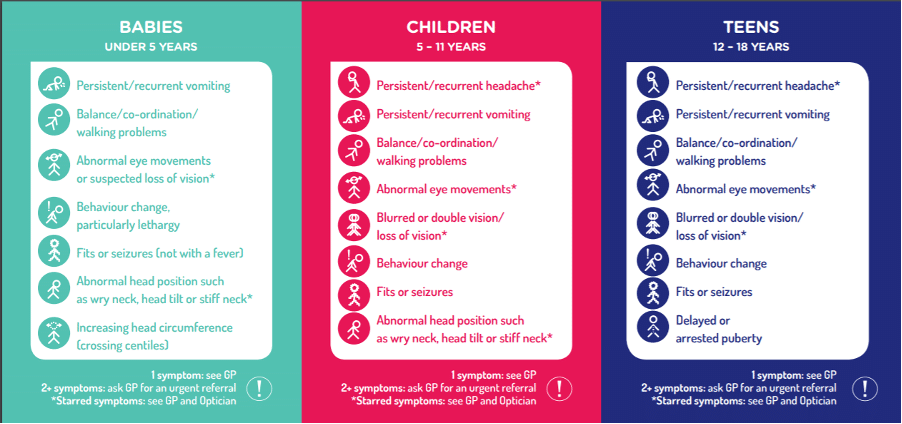

Clinical presentation of a child with a brain tumour varies with the child’s age, current development, and specific location of the lesion within in the CNS.

Symptoms/signs seen in brain tumours can be changeable and can be part of a broader picture of delayed milestones, neurodevelopmental delay, and differential education attainment.

Below are some common features seen in children with brain tumours.

History

- Headache: persistent or recurrent, day or night, may disturb sleep. Due to mass effect or hydrocephalus from blockage of CSF flow.

- Nausea / Vomiting: due to raised intracranial pressure (ICP).

- Behavioural change: usually due to tumours found in the frontal lobe.

- Polyuria/polydipsia: tumours can stop ADH production causing diabetes insipidus.

- Seizures: may be due to neuronal changes or chemical imbalance affecting normal electrical activity in the brain.

- Altered GCS

Remember: It is very important to take parental or carer insight, concern or anxiety about the child or young person’s symptoms seriously.

Examination

- General examination: Child’s behaviour, consciousness level and alertness

- Visual symptoms: diplopia, reduced visual acuity/visual fields, abnormal eye movement/fundoscopy

- Motor signs: abnormal gait or coordination, swallowing difficulties, weakness

- Delayed growth

- Delayed, arrest or precocious puberty

- Increased head circumference if under 2 years old (using growth chart to assess centile changes).

Remember: A normal neurological examination does not exclude a brain tumour.

Figure 1: Red flags of brain tumours by age group (Used with permission from HeadSmart UK https://www.headsmart.org.uk/ ) ∆

Differential Diagnosis

- Migraine or tension headaches are not uncommon in children, but persistent or changing headache requires reassessment and review of the diagnosis.

- Infection such as meningitis/encephalitis (more likely in the presence of fever, diarrhoea or recent contact with others with similar symptoms).

- Intracranial haemorrhage/stroke (knowledge of vascular territories can help aid diagnosis).

- Otitis media can present with unsteadiness/ataxic gait.

- Neurofibromatosis (NF), tuberous sclerosis (TS), Sturge-Weber syndrome, von Hippel-Lindau (vHL), and hereditary telangiectasia are well-known syndromes with CNS manifestations that can be non-neoplastic.4

Investigations

Imaging is the mainstay for diagnosis of brain tumours. MRI is the first choice but should this not be possible contrast enhanced CT should be performed. Sedation/general anaesthetic may be required to obtain an accurate image4.

Referral to the paediatric oncology MDT for further management and diagnostic review should follow results suggestive of a CNS malignancy.

Management

Initial management may include analgesia, antiemetics, anticonvulsants, fluid/dietary support, and treatment to lower intracranial pressure such as steroids.

Treatment options for CNS malignancy may include:

- Surgical resection – highly dependent on the location of the tumour, with the aim being complete removal of the tumour. In cases of associated hydrocephalus, the placement of CSF shunts devices may be appropriate.

- Radiotherapy – can be adjuvant to surgical resection or as a primary treatment method depending on the histological type.

- Chemotherapy – commonly used in situations where the tumour cannot be removed completely with surgery. The myelin derived Blood-Brain Barrier poses a particular challenge to chemotherapy as it may impair some treatments reaching their target site of action within the CNS

- Other possible treatments may be considered such as proton therapy (a form of radiotherapy) or stem cell transplants

All children with cancer should be offered the opportunity to take part in clinical trials if they are eligible.5

Longer-term management will include regular surveillance for relapse, recurrence, and effects of treatment. Fertility support and neuro-rehabilitation may be required following treatment.

Complications

The possible long-term effects depend on tumour type and location, modality of treatment received, and age of child when treated. Possible complications following treatment include:

- Epilepsy and seizures – this may require the use of anticonvulsant therapy

- Sleep disturbance – good sleep hygiene should be advised

- Effects on puberty/fertility – may require hormonal treatments and fertility preservation (sperm banking/egg or ovarian tissue freezing)

- Hearing loss

- Impaired growth – endocrine support may be required

- Cognitive impairment – extra education and development support at school may be required and should be explored with parents and teachers

- Secondary malignancy – children who receive radiotherapy are at increased risk of further cancers developing e.g meningiomas

Prognosis

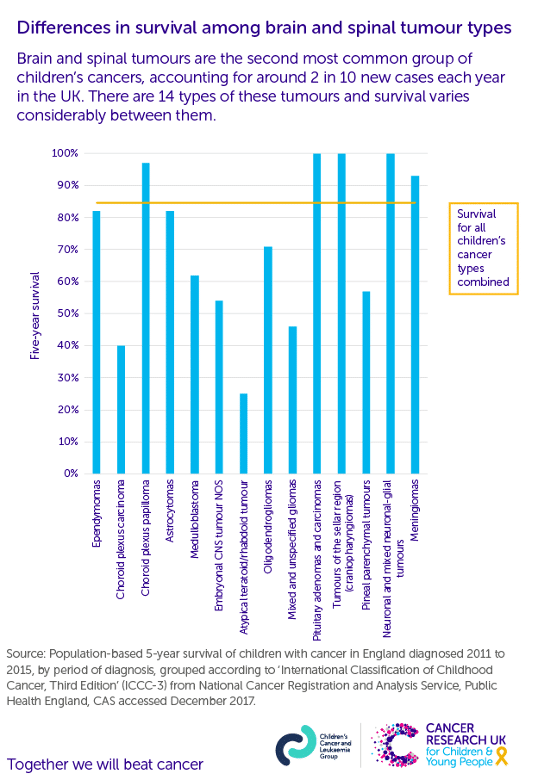

CNS tumours claim the lives of 100 children a year in the UK, one-third of all childhood cancer deaths.

Prognosis is highly variable between the different types of brain cancer:1

- The 5-year survival in England for all Brain and spinal tumours in children is 73%

- Low grade astrocytoma has a survival rate of about 95%

- High grade (anaplastic) astrocytoma has a survival rate of about 25%

- Ependymoma has a survival rate of about 80%

- Medulloblastoma, it is more than 60%

Figure 2: Five-year survival rates for different brain and spinal tumours in children∆∆ (Graph used with permission from the CCLG and CRUK)

References

| Number | Reference |

| 1 | Brain Tumours. Children’s Cancer and Leukemia Group. https://www.cclg.org.uk/Brain-tumours |

| 2 | Stiller, C.A., Bayne, A.M., Chakrabarty, A. et al. Incidence of childhood CNS tumours in Britain and variation in rates by definition of malignant behaviour: population-based study. BMC Cancer 19, 139 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-5344-7 |

| 3 | The Diagnosis of Brain Tumours in Children. An evidence-based guideline to assist healthcare professionals in the assessment of children presenting with symptoms and signs that may be due to a brain tumour. Quick Reference Guide. endorsed by the RCPCH. Version 3: March 2011. © Children’s Brain Tumour Research Centre, 2008.

|

| 4 | Subramanian S, Ahmad T. Childhood Brain Tumors. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535415/ |

| 5 | THE BRAIN PATHWAYS GUIDELINE: A GUIDELINE TO ASSIST HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONALS IN THE ASSESSMENT OF CHILDREN WHO MAY HAVE A BRAIN TUMOUR. Version 2 February 2017. Children’s Brain Tumour Research Centre, University of Nottingham |

| 6 | NICE Quality standard. Cancer services for children and young people. Published: 27 February 2014. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs55 |

| 7 | Types of Brain Tumours in Children. The Brain Tumour Charity. https://www.thebraintumourcharity.org/brain-tumour-diagnosis-treatment/types-brain-tumour-children/ |

| 8 | Survival Rates for Selected Childhood Brain and Spinal Cord Tumors. American Cancer Society. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/brain-spinal-cord-tumors-children/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html |

*Image used with Permission from HeadSmart: HeadSmart is a multi-award-winning, UK-wide campaign based on research funded by The Brain Tumour Charity at The University of Nottingham (2003-2006). The Brain Tumour Charity. Registered Charity in England and Wales (1150054) and Scotland (SC045081).

**Five-year survival rates for different brain and spinal tumours in children. Graph used with permission from the CCLG and CRUK.