“Quinsy” or peritonsillar abscess (PTA) is a collection of pus in the peritonsillar space, a potential space that surrounds the palatine tonsils. PTA is considered a purulent complication of tonsillitis (1) and is classed as a deep neck space abscess.

Although it is the most common and least life-threatening deep abscess, PTA requires urgent management to avoid progression to far more serious retropharyngeal or parapharyngeal abscesses.

It is often difficult to determine whether a patient has a true PTA with a pus collection, or simply peritonsillar cellulitis, until drainage has been attempted.

Epidemiology

Peritonsillar abscess is more common in young adults, with peak incidence between the ages of 20-40 years (1, 2). In the paediatric population, PTA tends to affect older children – it is uncommon to find a case in a child under 10 years old (2).

Despite being the most common complication of tonsillitis, PTA is still relatively uncommon. One American study found an annual incidence of 30.1 per 100,000 (3) and an average of 29 cases per year in UK hospitals (4)

Pathophysiology

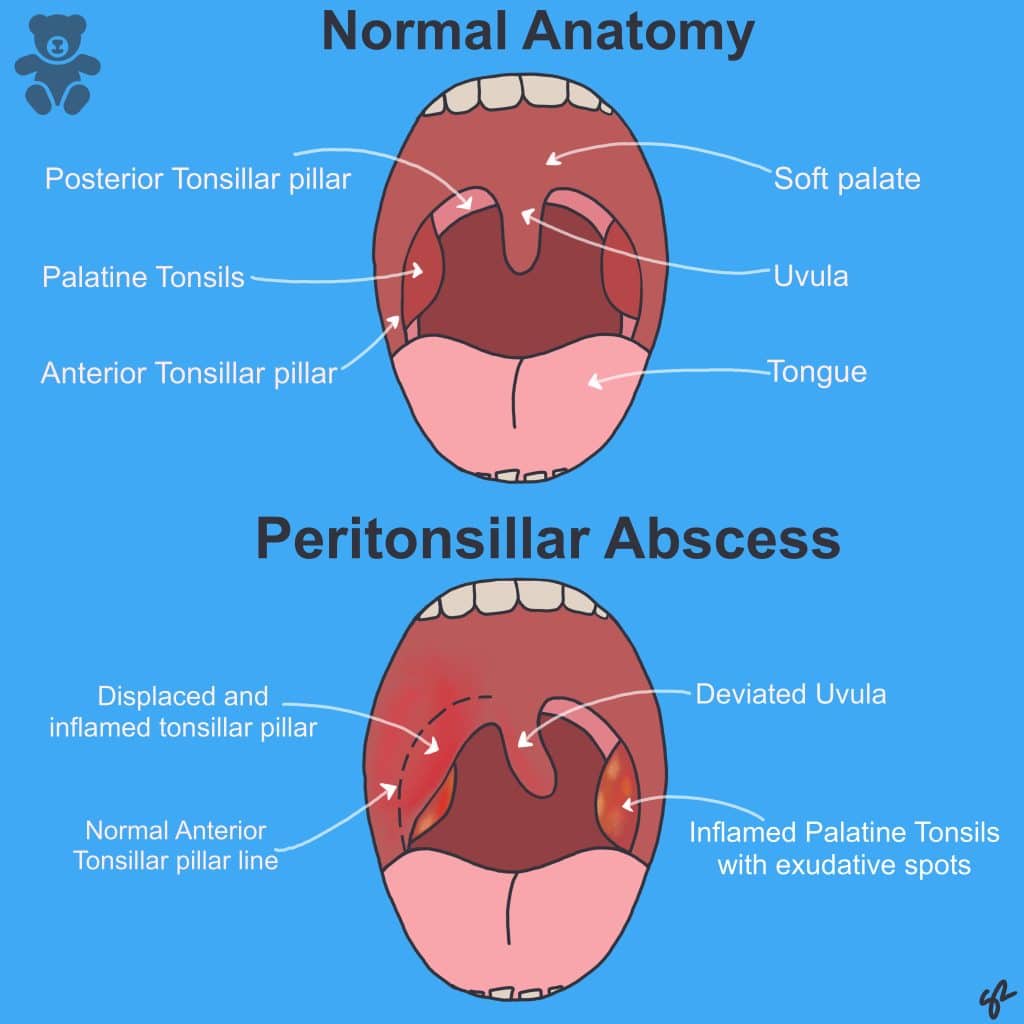

It is generally held that PTA occurs as a result of tonsillitis causing irritation and cellulitis in the peritonsillar space, followed by suppuration and collection of pus (Fig 1).

Anatomically, the tonsil sits in a depression between the anterior tonsillar pillar (formed by the glossopalatine muscle) and the posterior tonsillar pillar (formed by the pharyngopalatine muscle) (5).

The tonsil sits within a thin capsule that separates it from the superior constrictor muscles of the pharynx (6). In PTA, pus usually collects in the space between the tonsillar capsule and the superior pharyngeal muscles – an area solely occupied by connective tissue (6).

The most common causative organism is Streptococcus – often group A Streptococcus. Pus aspirated from PTA often contains both anaerobic and aerobic bacteria (in as many as 80% of patients depending on the study (7,8)) and the likely causative organism also varies slightly depending on age.

Fusobacterium necrophorum is more commonly isolated in 15-24 year olds, whilst group A Streptococcus is more common in 30-39 year olds (7).

As a result of the mixed causative organisms, antibiotic choice needs to cover both anaerobes and aerobes; co-amoxiclav is widely used (with clindamycin as an option for penicillin-allergic patients) (9,10).

Risk Factors

- Recurrent episodes of tonsillitis or partially treated episodes following multiple antibiotics (5)

- Significantly increased risk in smokers (11)

Clinical Features

Features in red are strongly suggestive of PTA as opposed to peritonsillar cellulitis.

From history

- Severe sore throat usually worse on one side (or unilateral entirely)

- Drooling/Unable to swallow own saliva

- Trismus (muscle spasm preventing jaw opening to full extent)

- “Hot potato” voice

- Halitosis

- Fever

- Otalgia

- Fatigue and irritability (secondary to dehydration and reduced intake)

(6) (2) (12)

From examination

- Unilateral tonsillar inflammation

- Deviation of uvula away from affected side

- Restricted opening of jaw

- Fullness/fluctuant swelling superior to the tonsil/ in posterior soft palate pushing the tonsil inferomedially

(2) (6) (12)

Differential Diagnosis

- Tonsillitis: Bilateral quinsy is rare (around 1% of patients in most studies (1, 13)). If there is bilateral inflammation, tonsillitis is a more likely diagnosis. If there is no resolution with appropriate antibiotic therapy, cross sectional imaging or attempts at drainage may be necessary.

- Peritonsillar Cellulitis (peritonsilitis): Often precedes PTA formation – similar presentation to PTA but trismus and uvula deviation are usually absent.

- Parapharyngeal/Retropharyngeal abscess: Tends to occur in younger children and usually has less tonsillar/peritonsillar inflammation. A patient with limited or no neck movement +/- airway compromise should prompt urgent senior assessment by both ENT and anaesthetics; there should also be consideration for cross sectional imaging (2, 12).

- Epiglottitis: A toxic, drooling child with changed character of voice may have epiglottitis. If there is stridor, respiratory distress, or the child is using accessory muscles, they should be kept with their parents and examination should be kept to a minimum until appropriate ENT and anaesthetic assistance is available. Epiglottitis tends to affect a younger age group and usually does not cause trismus (12).

Investigations

Laboratory tests

Standard blood tests should include:

- Full Blood Count (likely to show elevated white cell count, often with a neutrophil predominance)

- Urea and Electrolytes (patients may be significantly dehydrated due to reduced oral intake. Creatinine and urea may be elevated)

- C-Reactive Protein (often significantly raised)

- Glandular fever screen (PTA is associated in between 1 and 6% of cases(14,15))

Imaging or invasive tests

Imaging is not necessary in uncomplicated PTA, but is useful if complications are suspected (14). If spread into the parapharyngeal or retropharyngeal space (see differential diagnosis) is suspected, this will usually need confirmation with CT.

Management

- Definitive treatment is with aspiration or incision and drainage, although this is not always possible (depending on the child’s age).

- Antibiotics should cover anaerobic and aerobic bacteria; a common choice would be co-amoxiclav or benzylpenecillin and metronidazole. Clarithyomycin or clindamycin is used in a penicillin-allergic patient, dosed according to their age/weight (14).

- IV rehydration is important in those struggling to take fluids orally, or who are clinically dehydrated.

- Steroid therapy is controversial. It is frequently used in the treatment of adults with PTA as it is known to improve analgesic efficacy and oral intake (14). There is no definitive research into its use in paediatric patients. A meta-analysis conducted in 2012 advocated the use of 0.6mg/kg oral dexamethasone (up to 10mg) as a single one-off dose for pharyngitis and noted that it was particularly effective in exudative or Group A Strep. positive disease (16).

- Needle aspiration is generally accepted to be as effective as incision and drainage; it leads to equivalent lengths of stay and less pain post-procedure (17, 4, 14). Management is extremely dependent on the co-operation of the child. Older children may tolerate needle aspiration, whereas younger children may require a general anaesthetic and either drainage or a quinsy tonsillectomy (18).

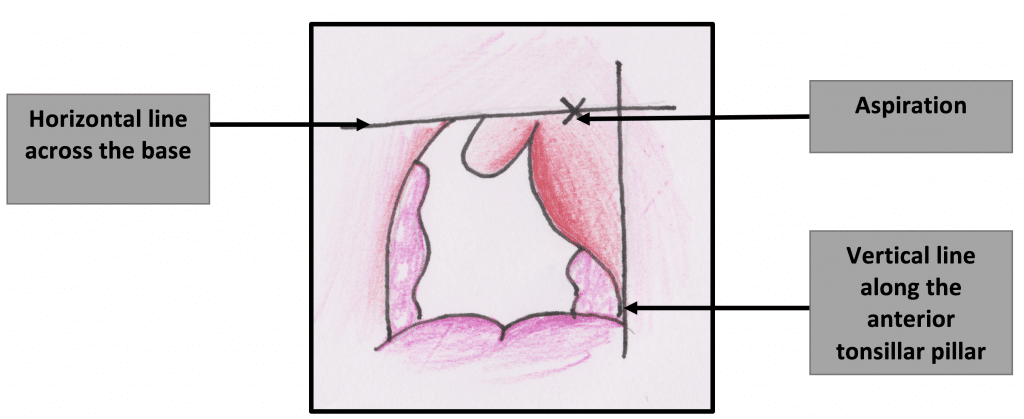

In those able to tolerate needle aspiration, it is carried out as follows:

- Local anaesthetic spray to the tonsils and tonsillar pillars (usually lidocaine or co-phenylcaine spray)

- A large bore needle (typically green or white) is attached to a 10 ml syringe

- Aspiration site should be the point of maximal fluctuance but should ideally be medial to the midpoint of a line drawn between the lateral border of the tonsillar pillar and the uvula on a horizontal plane in line with the top of the uvula (see diagram). This site of drainage minimises risk to the carotid, which lies posterolateral to the tonsil.

Case Study

A 15 year old boy presents to the GP with a 6-day history of odynophagia and dysphagia. His symptoms have worsened over the last 2 days and he is now only managing soup and fluids (as solids are too painful to swallow). The GP examines him and finds enlarged tonsils occupying most of the oropharynx but not meeting in the midline – there are streaks of exudate on both sides. There is some mildly tender cervical lymphadenopathy.

His observations are as follows; HR – 80, Temp 38°C, RR 18, Sats 97%, BP 110/45 mmHg.

Question 1: Is this a quinsy? (option 1 – yes, option 2- no)

Answer 1: No – there is no description of displacement of the anatomy or a supratonsillar swelling. Also, the child is able to swallow, is not drooling, and has an unaltered voice. Furthermore, there are streaks of exudate – making an alternative diagnosis more likely

Question 2: Of the following options, which is the most appropriate management?

- Admit the patient urgently to hospital via A&E

- Arrange for a same day ENT consultation

- Book a routine ENT clinic appointment

- Prescribe antibiotics and advise parents on the importance of regular analgesia and drinking. Advise to return if no improvement/worsening after antibiotics.

- Send child home with advice to parents to continue analgesia and make sure he keeps drinking. Advise parents that he is unlikely to need antibiotics.

Answer 2: Option 4 – this child most likely has bacterial tonsillitis as he has 3 out of the 4 centor criteria (see tonsillitis) and therefore it is appropriate to treat with antibiotics. Option 1 is inappropriate – however, if the child had stridor or other signs of airway compromise (either as a result of massively enlarged tonsils or more likely epiglottitis) or was extremely unwell with a marked tachycardia, hypotension and very high fever then A&E would be essential. Options 2 and 3 are not yet necessary, since the child is still able to drink and there is a clear likely diagnosis that can be safely treated as an outpatient. ENT consultation may become necessary if treatment fails or complications develop.

The GP diagnoses bacterial tonsillitis and prescribes a week’s course of oral penicillin V and Difflam™ mouthwash for pain relief.

Question 3: Could the GP have equally as reasonably prescribed co-amoxiclav?

Answer 3: Patients may have tonsillitis secondary to glandular fever; as there is a risk of a permanent skin reaction if patients with glandular fever are given co-amoxiclav, it is generally considered safer to give benzylpenecillin.

3 days later on the Monday morning, the patient returns to the GP surgery. He looks significantly worse with a flushed face and a hot potato voice. He explains that he got a little better on the first day of antibiotics, but since then has gotten much worse; he is now unable to swallow anything, including his own saliva.

His observations are now; HR 100, Temp 38.5°C, RR 20, Sats 96%, BP 95/40.

The GP re-examines his mouth and notices that the uvula is now pushed to the left-hand side and the tonsil seems to pushed downwards and medially by a bulge above it. The GP diagnoses a quinsy and makes a referral to hospital for a same day assessment by ENT.

Question 4: Which blood tests would be helpful in this child? (select multiple)

- FBC

- U&Es

- Glandular fever screen

- Pregnancy Test

- Urinary legionella

Answer 4: FBC and UE. FBC will show evidence of a neutrophilia and will demonstrate that the patient is mounting an immune response. U&Es are important since the patient is unable to eat and drink (he is likely to be dehydrated and hence at risk of pre-renal AKI). GF screen is not really necessary – glandular fever is an extremely rare cause of quinsy (see above).

Question 5: What is the definitive treatment of this condition? (select multiple)

- Steroids

- Aciclovir

- IV antibiotics

- Oral Antibiotics

- Drainage of pus

- Surgery

Answer 5: The pus needs to be drained either by incision and drainage or aspiration; this will provide rapid symptomatic relief and reduce the risk of complications. Steroids are extremely helpful for reducing trismus, to allow better access for drainage. Antibiotics will eradicate the causative infection and are usually given IV since the patient can’t swallow.

The patient is admitted to hospital where he is seen by the paediatric team who insert a cannula and initiate IV maintenance fluids. Bloods are also taken, including; LFTs, FBC, U&Es and a CRP. The patient is seen by the SHO who agrees with the GP’s diagnosis of a quinsy. She aspirates the peritonsillar space using a large gauge needle and lidocaine spray; she collects 8mL of pus. She starts IV benzylpenecillin and gives a single dose of IV steroids. The patient’s bloods show a WCC count of 16 x10^9/L, creatinine of 100, and a urea of 10mmol/L. The following morning, the patient is seen on ward round by the ENT registrar. His symptoms have much improved; he has managed some yoghurt and is able to talk much more easily. The patient is discharged the following day after 2 nights in hospital. At discharge, his U&Es have returned to normal and his white cell count is falling. He is discharged with a further 7 day course of oral penicillin V.

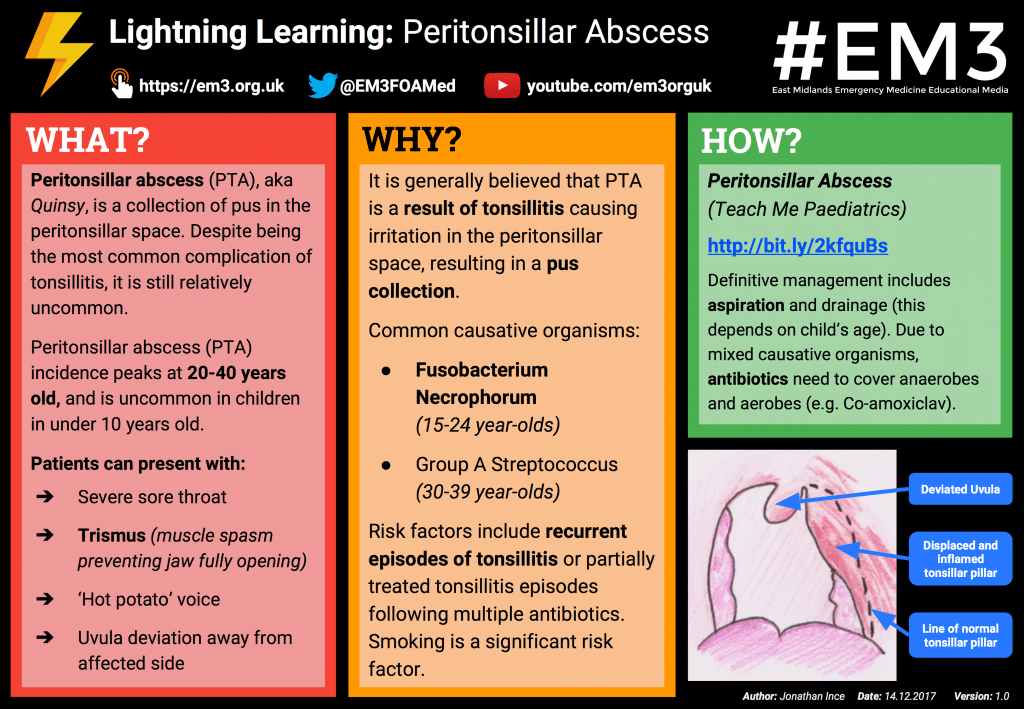

Lightning Learning

Thanks to the team at www.em3.org.uk we now have a ‘Lightning Learning’ resource for you to take away.

References

| (1) | Epidemiology, clinical history and microbiology of peritonsillar abscess. E. Mazur, E. Czerwiriska, I. Korona-Glowniak, A. Grochowalska, M. Koziol-Montewka. 2014, European Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, pp. 549-554. |

| (2) | Brook, Itzhak. Pediatric Peritonsillar Abscess. Medscape. [Online] May 04, 2016. [Cited: October 28, 2016.] http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/970260-overview#a6. |

| (3) | Harris P. Mosher Award thesis. Peritonsillar abscess: incidence, current management practices, and a proposal for treatment guidelines. FS, Herzon. 1995, Laryngoscope, Vol. 105, pp. 1-17. |

| (4) | National audit of the management of peritonsillar abscess. Mehanna, HM, Al-Bahnasawi, L and White, A. 923, September 2002, Postgrad Medical Journal, Vol. 78, pp. 545-548. |

| (5) | Peritonsillar Abscess: Diagnosis and Treatment. Steyer, T.E. 65, Jan 2002, Vol. 1, pp. 93-97. |

| (6) | Gosselin, J. Benoit. Peritonsillar Abscess. Medscape. [Online] Dec 16, 2015. [Cited: October 28, 2016.] http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/194863-overview#a10. |

| (7) | Incidence and microbiology of peritonsillar abscess: the influence of season, age, and gender. Klug, T.E. 7, 2014, European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, Vol. 33, pp. 1163-1167. |

| (8) | A review of the pathogenesis of adult peritonsillar. Emily L. Powell, Jason Powell, Julie R. Samuel and Janet A. Wilson. 2013, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, Vol. 68, pp. 1941-1950. |

| (9) | Krakovitz, Paul, et al. https://www.clinicalkey.com/#!/content/medical_topic/21-s2.0-1014282. Clinical Key. [Online] JULY 24, 2013. [Cited: SEPTEMBER 07, 2016.] https://www.clinicalkey.com/#!/content/medical_topic/21-s2.0-1014282. |

| (10) | National UK survey of antibiotics prescribed for acute tonsillitis and peritonsillar abscess. V Visvanathan, P Nix. 2010, The Journal of Laryngology & Otology, pp. 420-423. |

| (11) | Smoking promotes peritonsillar abscess. Klug, TE, et al. 12, November 2013, Vol. 270, pp. 163-167. |

| (12) | Wald, E.R. Peritonsillar Cellulitis and Abscess. Up To Date. [Online] March 08, 2016. [Cited: October 28, 2016.] https://www.uptodate.com/contents/peritonsillar-cellulitis-and-abscess?source=search_result&search=peritonsillar%20abscess&selectedTitle=1~47. |

| (13) | Changing trends of peritonsillar abscess. Marom, T, et al. 3, 2010, American Journal Of Otolaryngology, Vol. 31, pp. 162-167. |

| (14) | An evidence-based review of peritonsillar abscess. J, Powell and JA, Wilson. 2, Vol. 37, pp. 136-145. |

| (15) | Screening for glandular fever in patients with Quinsy: is it necessary? MM, Shareef, Balaji, N and Adi-Romero, P. 11, Jun 14, 2007, European Archives of otorhinolaryngology, Vol. 264, pp. 1329-1331. |

| (16) | Steroids as adjuvant treatment of sore throat in acute bacterial pharyngitis. Schams, S.C and Goldman, R.D. 1, January 2012, Canadian family physician, Vol. 58, pp. 52-54. |

| (17) | Comparison of Needle Aspiration with Incision and Drainage for the Treatment of Peritonsillar Abscess. Chi, T.H, Yuan, C.H and Tsao, Y.H. 1, 2014, West Indies Medical Journal, Vol. 1. |

| (18) | Peritonsillar abscess in children: a 10-year review of diagnosis and management. Schraff, S, McGinn, J.D and Derkay, C.S. 3, 2001, Vol. 57, pp. 213-218. |

Authors:

1st Author: Dr Thomas Stubington

Senior Reviewer: Dr Raguwinda Sahota (Senior ENT registrar)

Student Reviewer: Luke Austen