This article is based on guidance from the Advanced Life Support Group guidelines for paediatric basic and advanced life support. The content is provided as an information resource only and is not to be used or relied on for any diagnostic or treatment purposes. Local or national up to date guidelines should be sought for the care of the patient.

Introduction

The seriously unwell child presents a daunting case, even for the most experienced of clinicians. However, the adoption of a calm and structured approach to assessment and management of the patient, enables the clinician to identify and treat life threatening problems in a methodical manner.

The outcome for children following cardiac arrest, is in general, poor and therefore the emphasis in on early recognition of the signs of potential respiratory, circulatory or central neurological failure, to help prevent the downward spiral to an arrest situation.

A key point to note is that in a healthcare environment you are rarely alone – always ask early for help in these situations. This may involve making a paediatric emergency (or crash) when in a hospital, for which the universal number is 2222.

The structured approach to the seriously ill child can be divided into the following sections:

- Primary ABCDE assessment and resuscitation

- Secondary assessment and emergency treatment

- Stabilisation and transfer

Primary ABCDE assessment and resuscitation

The initial rapid assessment of a child should take less than a minute. The aim of this is to identify life threatening problems to guide resuscitation. It should take less than a minute. The table below outlines the aspects of the assessment, after which they are discussed in greater detail.

| Airway and Breathing | Circulation | Disability | Exposure |

| Effort of breathing | Heart rate | Conscious level | Fever |

| Respiratory rate

and rhythm |

Pulse volume | Posture | Rash |

| Stridor / wheeze | Capillary refill | Pupils | Bruising |

| Auscultation | Skin temperature | ||

| Skin colour |

Airway assessment

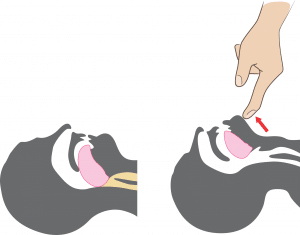

Look, listen and feel for airway patency. In an unconscious baby or child, open the airway using the “head tilt chin lift” manoeuvre (figure 1). The differences in airway anatomy as children mature, means that the desirable degrees of tilt is neutral in an infant and a ‘sniffing’ position in a child. If this manoeuvre is unsuccessful in establishing airway patency, a jaw thrust may be used.

Figure 1. Opening the airway using head tilt chin lift

Resuscitation

In an in-hospital setting, adjuncts such as naso-pharyngeal airways and Guedel airways may also be appropriate. In a conscious child, stridor or hoarse voice may indicate a compromised airway and senior help must be sought promptly. If there is any concern that a child’s airway is becoming compromised within the hospital, anaesthetic help must be requested urgently.

Breathing assessment

During this examination, you should make an assessment of the effort, the efficacy and the effect of breathing:

- Effort: ‘How much work is going into breathing?’

A raised respiratory rate may be caused by airway or lung pathology or be driven by a metabolic acidosis (for example in diabetic ketoacidosis.) Of course, identifying a raised respiratory rate relies upon knowing the normal values, these can be found on the paediatric early warning score charts and are given below:

| Age (years) | Normal range of respiratory rate (bpm) |

| <1 | 30-40 |

| 1-2 | 25-35 |

| 2-5 | 25-30 |

| 5-12 | 15-25 |

| >12 | 12-20 |

Other signs of respiratory distress include grunting, flaring of the nostrils, tracheal tug and accessory muscle use (intercostal, subcostal or at the most severe sternal recession). Gasping is a late sign of severe hypoxia. In some children, despite hypoxia there will be no signs of increased respiratory effort – these are:

- Those who have had severe respiratory problems for some time and have become fatigued. Exhaustion (seen in life threatening asthma) is a pre terminal sign

- Neuromuscular disease – such as muscular dystrophy

- Central respiratory depression (from raised intracranial pressure, poisoning or encephalopathy)

- Efficacy: ‘What are they achieving in terms of air movement and gas exchange?’

Observation of chest expansion and auscultation for air entry in combination with oxygen saturations are important here. You may identify the asymmetrical air entry and bronchial breath sounds of a pneumonia or the wheeze and reduced air entry of acute asthma. Note a silent chest is an extremely worrying sign.

- Effect: ‘What is the effect of respiratory inadequacy on the rest of the body?’

Hypoxia will initially lead to tachycardia, however if it is prolonged or severe this will lead to bradycardia, which is a pre terminal sign. Likewise, cyanosis is visible with saturations below 70% and again is a late and pre terminal sign. Hypoxia or hypercapnia will lead to agitation or drowsiness, which may present as the child who will not cooperate with examination and seems very distressed or alternatively, unusually quiet and withdrawn.

Video 1. This video demonstrates various signs to look for when assessing the breathing of a child. (Video courtesy of OPENPediatrics, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Esqp0gPXz6Y)(3)

Resuscitation

All children with respiratory difficulty or hypoxia should be given high flow oxygen (15litres/min) through an oxygen mask with a reservoir bag. If there is also inadequate respiratory effort, then use a bag-valve mask and consider intubation and ventilation as appropriate.

In a choking patient who is conscious and seems to be coughing effectively, encouraging coughing is often all the intervention required. If the cough has become ineffective, 5 back blows followed by 5 chest thrusts in a baby/abdominal thrusts in a child are used to attempt to dislodge the foreign body. If they lose consciousness, the life support algorithm is followed. See our choking article for more information.

Circulation assessment

Record the patient’s heart rate, pulse volume, capillary refill time and blood pressure. Children are very good at compensating for alterations in their physiology and as such hypotension is a late sign. Assess the effect of any circulatory inadequacy on other organs. These may include a raised respiratory rate (driven by the resultant metabolic acidosis), reduced urine output, mottled skin with pale, cool peripheries (due to poor skin perfusion) or altered mental state.

Resuscitation

If there are signs of circulatory compromise, establish venous or intraosseous access rapidly and give a 20ml/kg bolus of 0.9% sodium chloride. Further boluses should be guided by reassessment and inotropic support considered if more than two boluses are needed. Note in DKA, the initial bolus is 10ml/kg due to the risk of cerebral oedema. Venous access in seriously ill children is often difficult and fluid bolus administration should not be delayed by repeated attempts at cannulation – intraosseous access is rapid and effective and should be considered early.

Disability (neurological) assessment

Assess the child’s conscious level using the AVPU score (where A is alert, V is responds to voice, P is responds to pain and U is unresponsive) or GCS. The AVPU scale is quicker to use with a response only to pain correlating with a GCS score of 8.

Many children suffering from a severe illness are floppy. Stiff posturing such as that in decorticate (flexed arms, extended legs) or decerebrate (extended arms and legs) suggests serious brain dysfunction.

Pupil size and response to light should be recorded. Bedside blood sugar testing should also be performed (although in reality this may have been checked with a blood gas at the time of obtaining IV or IO access). Consider raised intracranial pressure in any child with depressed conscious level. The presence of hypertension and bradycardia in such cases indicates impending coning.

Resuscitation

- Consider intubation to stabilise the airway in any child with a conscious level graded as P or U.

- Treat hypoglycaemia with a bolus of 2ml/kg 10% glucose IV or IO, followed by a glucose infusion to prevent recurrence.

- In cases of suspected raised intracranial pressure consider mannitol and neuroprotective measures (see full guideline for further details.)

Exposure assessment

A swift head to toe examination of the child may provide clues as to the aetiology of the illness, for example a purpuric rash may only be noted on full exposure or surgical scars may prompt you to consider particular histories. Be careful to ensure exposed areas are recovered to help maintain temperature control and preserve the child’s dignity.

Secondary assessment and emergency treatment

Once immediately life threatening problems have been addressed, move on to assess the patient in further detail. This includes:

- Reassessing the response to initial resuscitative measures

- Taking a focused history

- Performing detailed systems based examinations where appropriate

- Further investigations – these may include laboratory blood tests, ECG, radiographs or other imaging such as CT

Below, some specific conditions and their emergency treatment are discussed in further detail.

Airway and Breathing

The table below outlines the other clinical features which may be found in the child with respiratory distress and which diagnoses they point towards:

| Clinical findings | Diagnosis | Emergency treatment |

| Bubbling sound | Excessive secretions | Suctioning |

| Harsh stridor and a barking cough | Croup | Oral dexamethasone

Nebulised budesonide and adrenaline in severe cases |

| Soft stridor, drooling and fever in a sick looking child | Bacterial tracheitis or epiglottitis | Intubation by anaesthetist followed by IV antibiotics |

| Sudden onset stridor with history of inhalation | Inhaled foreign body | Laryngoscopy for removal |

| Stridor following ingestion or injection of a known allergen | Anaphylaxis | IM adrenaline |

| Wheeze | Acute asthma | Bronchodilators |

| Bronchial breathing | Pneumonia | IV antibiotics |

Circulation

Congenital heart disease

This is one of the most common types of birth defect. Although many of those affected are now identified by antenatal scanning or during the newborn baby check, some first present to the ED within a few days of life. This is because at this time the heart is still undergoing changes, converting from the foetal to neonatal circulation.

One of the major structural changes is the closure of the ductus arteriosus, a connection between the pulmonary artery and the descending aorta. This reveals those who are dependent upon this duct to enable mixing of blood to maintain their systemic or pulmonary circulations.

Presentation of duct dependent lesions can vary widely from subtle symptoms of poor feeding, sleepiness and slightly fast breathing when the duct is starting to close, to the collapsed baby in cardiogenic shock where closure is imminent. This can often be a diagnostic challenge, since the decompensated patient with sepsis or an inborn error or metabolism can have a very similar presentation.

If a duct dependent lesion is suspected, IV dinoprostone should be administered – this helps to keep the duct open, therefore allowing common mixing to occur until a definitive diagnosis and treatment by a cardiologist can be sought.

Supraventricular Tachycardia (SVT)

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) is the most common arrhythmia seen in children. Older children with SVT typically present with episodes of palpitations, chest pain and dizziness. Babies may present in extremis with signs of heart failure, following prolonged episodes of SVT which have not been detected. If SVT is identified on a 12 lead ECG, further treatment involves a trial of vagal manoeuvres followed by a rapid bolus of IV adenosine or synchronous DC shock, depending upon the clinical status of the child.

Disability (neurological)

Seizures

Seizures are common – 1 in 20 people experiencing one in their lifetime. Most often they are brief (less than 5 minutes) and witnessed by parents, the child presenting to the ED in a stable condition. However, sometimes seizures are prolonged and ongoing at time of ED arrival requiring urgent intervention. If seizure activity is ongoing at 20 minutes or there are shorter seizures with incomplete recovery between, this is defined as status epilepticus.

The algorithm for the management of status epilepticus is a relatively simple flow chart but complications come with keeping an awareness of the duration of the seizure and therefore the timings for and the correct dosing and preparation of the drugs required. Benzodiazepines also have a tendency to cause respiratory depression and support measures may be needed.

Exposure

Sepsis

Sepsis is one of the commonest causes of serious illness in children and should always be considered in a child who is either inexplicably unwell or who remains unwell despite maximal therapy for another condition. Fever is not always present and particularly in babies, hypothermia may occur.

Ideally, cultures of blood, urine and CSF (in young babies or those with signs of intracranial infection,) should be obtained prior to administering antibiotics. However, if sampling proves problematic or the patient is too clinically unstable then antibiotics should be given as soon as possible. Each hospital will have their own guidelines for antibiotic choices.

Stabilisation and transfer

Regular reassessment is essential in the ongoing care of any unwell child. All patients should have the following monitored:

- Oxygen saturations (plus CO2 monitoring if intubated)

- Pulse rate and rhythm

- Blood pressure

- Urine output

- Core temperature

Transfer may be within the hospital for imaging or to HDU/ICU for ongoing care. There are rare occasions where paediatric patients require emergency inter – hospital transfer, to allow life-saving intervention which is not readily available onsite and which cannot wait for stabilisation or retrieval. An example would be a child with an expanding intracranial haemorrhage who requires immediate neurosurgical intervention at the nearest paediatric neurosurgical facility.

Coordinating the care and timely transfer of these children relies upon collaborative team working from many departments – ED, Anaesthetics, Children’s Intensive Care, Ambulance Service and Radiology.

References

| (1) | https://www.resus.org.uk/resuscitation-guidelines/paediatric-basic-life-support/ |

| (2) | https://www.resus.org.uk/resuscitation-guidelines/paediatric-advanced-life-support/ |

| (3) | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bzV1C44IPBc |

Authors:

1st draft: Dr Amanda Friend

Senior Review: Dr Jennifer Mann (Paediatric Specialist Registrar)