Introduction

Epistaxis is bleeding from the nose – a common presentation in children. Epistaxis is usually manageable with simple first aid measures and advice on behavioural triggers (nose-picking). Epistaxis can be acute or recurrent. Recurrent epistaxis can sometimes indicate an underlying pathology e.g. angiofibroma or coagulation disorder.

Epidemiology

Although epistaxis is fairly common amongst the entire population, epistaxis has a bimodal distribution due to different causative factors. In children the most common causative factor is nose-picking. Narrower nasal airways seen in children are also more prone to bleeding and inflammation in general. In the elderly population the trigger is often an anti-coagulant medication to treat or prevent other medical conditions. Epistaxis in children under the age of 2 is relatively rare and should be referred to ENT for investigation.

Pathophysiology

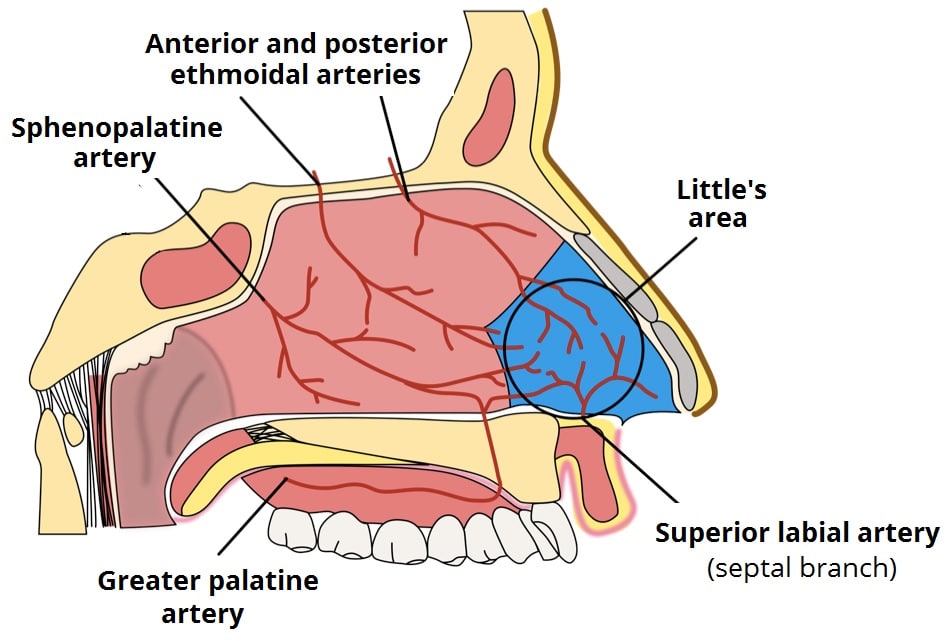

Most epistaxis comes from Little’s area (fig.1) which is a confluence of blood vessels originating from the internal carotid arteries (anterior and posterior ethmoidal) and external carotid arteries (greater palatine, sphenopalatine, superior labial and lateral nasal arteries) This area sits on the anterior portion of the septum bilaterally.

Fig.1: Little’s area and the arterial supply to the nose

The main causes of acute epistaxis in children are:

- Trauma – e.g. nose picking, sneezing, rubbing, coughing, injury to nose

- Mucosal irritation – e.g. dry air, URTIs, steroid use

- Clotting abnormalities – either hereditary or acquired. Epistaxis is usually the major presenting feature of common clotting abnormalities such as Von-Willebrand’s disease or genetic conditions such as hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT).

Recurrent epistaxis can be caused by the same insults but can also indicate an underlying coagulopathy and a full clinical and family history should be explored. Recurrent epistaxis can rarely be caused by an underlying JNA (juvenile nasal angiofibroma) which are most common in males aged 12-20.

Risk Factors

As well as those detailed in ‘pathophysiology’ there are recognised risk factors amongst children, mostly as they lead to those aforementioned:

- Activities involving altitude e.g. skiing

- Strenuous physical activities with risk of nasal trauma or straining/raising ICP e.g. rugby, gymnastics

- Coagulopathies

- Hayfever or regular URTIs

- Medication use (rare)

Clinical Features

From History

Usually the child will present with spontaneous bleeding. Children (or carers!) may report nose picking or other trauma prior to the episode.

From Examination

If bleeding is not profuse, you may be able to see the source on the anterior septum of the affected side.

If there is any history of external trauma, you must examine for evidence of a septal haematoma (fig.2) as these need urgent review by ENT and drainage to avoid permanent disfigurement.

Differential Diagnoses

Foreign body – foreign bodies should be visible with anterior rhinoscopy and may be accompanied with a history of eating small food e.g. peas or sweetcorn or playing with beads etc. A foreign body should be ruled out in children presenting with unilateral offensive nasal discharge which can often be mixed with blood.

Investigations

Acute epistaxis rarely needs investigating in children. If a large volume blood loss is suspected from the history or examination, blood tests (FBC, Clotting profile) may be useful in quantifying this and offering a guide as to whether this patient may need transfusing. Blood tests can also demonstrate any underlying coagulopathy in the case of a large volume epistaxis.

Recurrent epistaxis, particularly from the same nostril or in males aged 12-20 should be referred to ENT for flexible nasal endoscopy (FNE) to exclude a JNA or other unilateral pathology e.g. polyp. Typically, these patients have intermittent large volume bleeds. An endoscopic examination of the nose can be done by the ENT team in the outpatient department to rule this out.

Management

Initial first aid

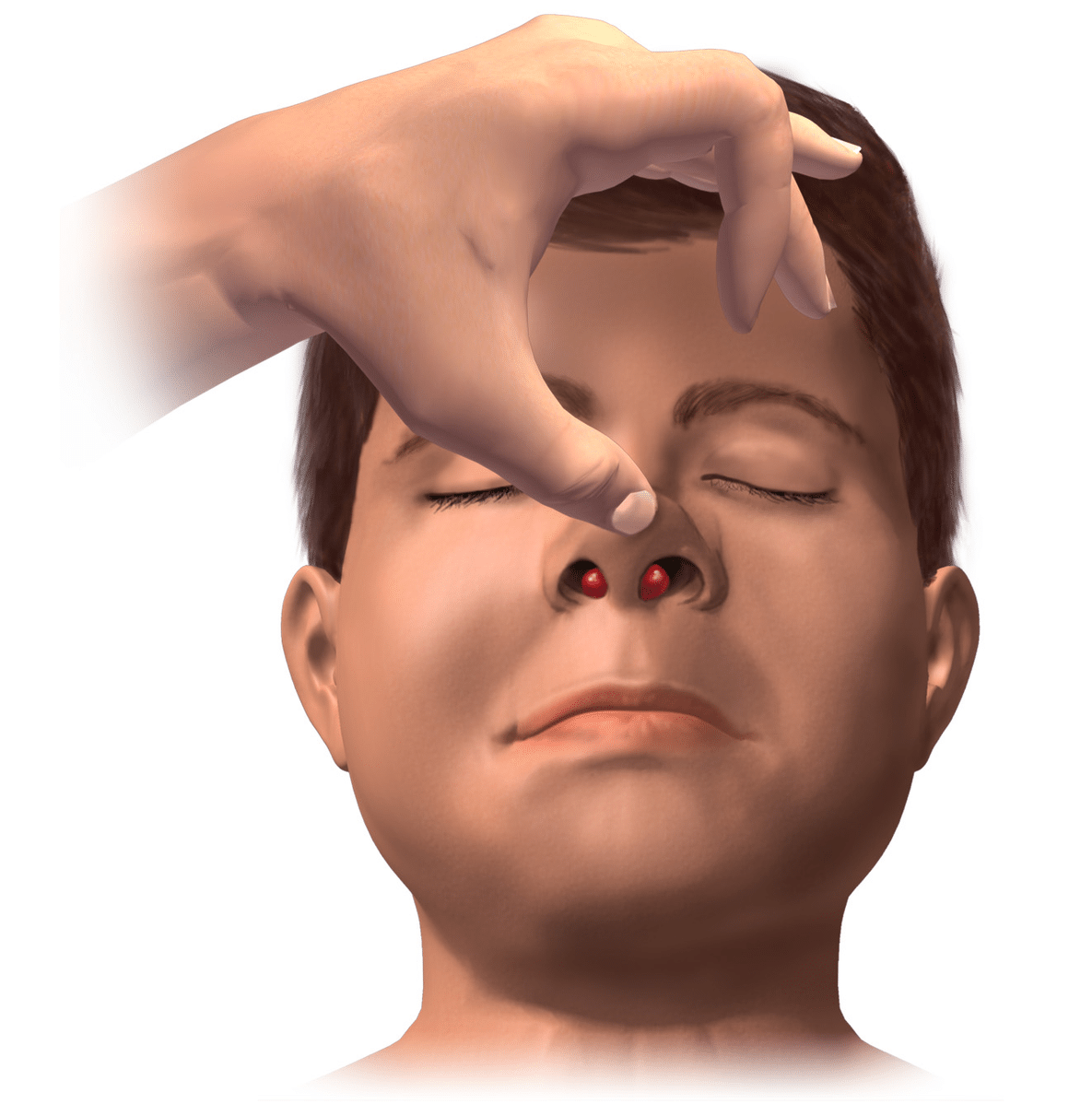

-Lean the child forwards over a bowl and encourage them to spit any blood out of their mouth

–Pinch the soft part of the nose and hold for at least 15 minutes without releasing pressure

-Try to keep children as calm as possible. This can be a frightening experience if happening for the first time

-Check for cessation of bleeding. If not, pinch again for 15 minutes and apply an ice pack either to the nape of the neck or forehead. Alternatively the child can suck on an ice cube

-Check for cessation of bleeding. If not, the child needs to be seen by a medical practitioner

Primary care/ A&E management

-Look for any bleeding points inside the nose by using a bright light.

-If available, a local anaesthetic/decongestant spray should be applied to the septum such as co-phenylcaine

-If any bleeding points are identified, obtain verbal consent from parent for nasal cautery with silver nitrate. Risks include septal perforation, failure and pain. Parents and children should be warned that the fluid from the chemical reaction can seep out of the nasal cavity and stain the skin. If this occurs it leaves a discoloured mark which takes a few weeks to return to normal.

-Use a circular motion with the silver nitrate stick from outside to the centre of the bleeding point. Do not make contact for longer than 15seconds. Do not cauterise both sides of the septum in the same episode.

-If bleeding continues, call ENT who will consider placing an anterior or a posterior nasal pack in rare cases. Once packed these patients need admitting under ENT.

-In cases where nasal injury and deformity have occurred and bleeding is persistent, reduction of any nasal fractures may help to stem the bleeding. You may wish to do this with a senior or ask for the assistance of the ENT team.

-In recurrent cases, a full blood count and clotting profile should be checked. Any clotting abnormalities noted should warrant a repeat clotting profile and discussion with a haematologist.

Definitive management

Once bleeding has stopped and packs (if required) have been removed, patients should be discharged with Naseptin ointment BD for 2 weeks. Alternatives in peanut allergy are Bactroban or simply Vaseline.

Naseptin contains peanut oil and should not be given to any child who has a peanut allergy or lives with anyone with a severe peanut allergy.

Counsel the parents on how to administer the Naseptin ointment without putting the nozzle inside the nostril. Place a pea sized amount on the finger and present the finger to the opening of the nasal cavity and place the cream in the nose without pushing the finger inside the nasal cavity. This can then be massaged externally.

Children and carers should be advised that certain factors may result in reoccurrence and to avoid, where possible, for up to 2 weeks. These include:

-Strenuous physical activity

-Bending forwards e.g. to tie shoelaces

-Hot drinks/food/showers (steam can irritate the inside of the nose)

-Blowing their nose

-Picking their nose

-Spicy food

The definitive management of recurrent epistaxis depends on the underlying cause. Red flags that may indicate an urgent referral to ENT include:

-Persistent unilateral bleeding

-Weight loss

-Visual disturbance

-Facial pain

Complications

Epistaxis, both acute and recurrent, often has no trigger or underlying cause identified, which can be frustrating for patients and their relatives. Once a blood vessel has been damaged within the nose, it remains vulnerable until fully healed and so if treatment and avoidance advice is not adhered to strictly, they will often rebleed for a few weeks.