Introduction

Laryngomalacia is the most common congenital airway disorder and the most common cause of stridor in neonates. Whilst most cases will not have associated respiratory distress and are self-limiting over several months, severe cases may be life-threatening and may require surgical intervention.

Epidemiology

Laryngomalacia normally presents within the first few weeks of life and resolves within the first two years, although in rare cases it can extend later into childhood. Symptoms peak at 6-8 months when respiratory function increases before the larynx (and hence diameter for airflow) increases in size.

Pathophysiology

Although the underlying pathophysiology is unclear, the condition is characterized by immature laryngeal cartilages collapsing over the inlet to the larynx causing inspiratory stridor. In particular these cartilages are:

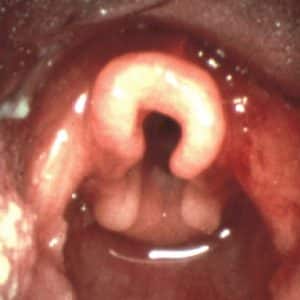

- A long, curled, ‘omega-shaped’ epiglottis

- Tall, bulky aryepiglottic folds

Figure 1: Image showing laryngomalacia. Note the omega shape (Ω) of the epiglottis seen in laryngomalacia

Risk factors

Different theories exist as to why this abnormal cartilage occurs including immaturity of the cartilaginous structure or unco-ordinated neuromuscular laryngeal movement. However, no evidence has been found from histological or neurological studies and the condition is not more common in premature infants.

Patients with neuromuscular disease (either acquired or congenital) do appear to have a higher incidence of laryngomalacia. Patients with more severe presentations are also more likely to have associated airway lesions such as vocal cord paralysis, subglottic stenosis and tracheomalacia.

Clinical features

Key signs and symptoms of laryngomalacia are:

- High-pitched inspiratory stridor worse on lying flat or on exertion

- Normal cry (but stridor may be worse when distressed)

For the majority of patients (approx. 80%), symptoms are mild with the stridor being intermittent and not accompanied with other symptoms and no impact on growth. Episodes may occur with a concurrent URTI which may cause mild inflammation, mucosal oedema and associated narrowing of the airway.

Signs of more severe cases include:

- Respiratory distress

- Dyspnoea with intercostal / sternal recession

- Feeding difficulties or episodes of suffocation/cyanosis whilst feeding

- Poor weight gain

- Obstructive sleep apnoea

Loudness of stridor is not a good marker of severity as severe cases may have no real stridor due to reduced airflow. Desaturation is also a very late sign in airway compromise and is indicative of a life-threatening condition.

Differential diagnosis

Other airway disorders which occur in neonates and may present with similar stridor and respiratory distress include:

- Vocal Cord Paralysis

- Bilateral vocal cord palsy is most commonly congenital and approximately half will require tracheotomy.

- Unilateral vocal cord palsy is most common following surgery, causing recurrent laryngeal nerve injury.

- Subglottic stenosis

- Due to defective development of cricoid cartilage

-

- Can be identified with flexible laryngoscopy. May be seen as ‘Steeple sign’ on CXR.

- Tracheomalacia

- Due to weakness of tracheal cartilages

- Most common in 0-12 months

- Diagnosis confirmed with flexible laryngoscopy without anaesthesia followed by tracheobronchoscopy under general anaesthesia.

- Laryngeal Atresia

- Usually identified on antenatal ultrasound

- Incompatible with life unless immediate tracheotomy is performed following elective C-section with neonate still on placental circulation.

- Laryngeal Cleft

- Acquired

- Croup (Laryngotracheobronchitis)

- Uncommon before six months.

- Bark like cough following upper respiratory tract infection

- Bacterial Laryngitis / Tracheitis

- Similar presentation to croup but quicker onset and more systemically unwell.

- Supraglottitis / Epiglottitis

- Children >2yo

- Rapid onset sore throat, dysphagia, drooling, stridor and dyspnoea

- Reduced incidence due to Haemophilus vaccination

- Trauma

- Laryngeal fractures can be caused by direct blunt trauma or strangulation

- May not show significant external signs but may have bruising or crepitus (surgical emphysema)

- Laryngeal fractures are very rare in infants due to the force required and non-accidental injury should be considered in these cases

- Croup (Laryngotracheobronchitis)

Investigations

The key investigation for confirming laryngomalacia is flexible endoscopy (laryngoscopy) via the nose or mouth to view the larynx and laryngeal cartilages. This requires dynamic examination whilst the child is conscious.

In severe cases or where flexible laryngoscopy can not identify the cause of stridor, it is possible that the patient has a lesion below the level of the vocal cords (subglottic) and will require rigid endoscopy under general anaesthesia.

Management

Mild Cases

Most (~90%) of cases are mild and do not require treatment. Parents should be reassured that the condition will resolve by 12-16 months but symptoms may peak at 6 months and may be exacerbated following respiratory tract infections.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux can exacerbate symptoms and appropriate anti-reflux medications may be considered.

Severe Cases

Symptoms of severe laryngomalacia include feeding difficulties, faltering growth, respiratory distress and apnoeas. Some severe cases of laryngomalacia may undergo elective surgery (e.g. Endoscopic aryepiglottoplasty aka supraglottoplasty) to improve symptoms and support development.

Life-Threatening Cases

Some severe cases may develop worsening stridor and respiratory distress which may be exacerbated by an upper respiratory tract infection resulting in severe airway compromise. These severe cases should be managed as follows:

- Try to keep the child calm. Child can be observed in parent’s arms.

- Involve senior paediatrician / anaesthetics / ENT team early on.

- Ensure they are in a safe and appropriate environment. E.g. Resus / HDU.

- If maintaining own airway consider:

- Humidified oxygen

- Nebulised adrenaline (1ml of 1/1000 with 4ml of normal saline)

- Oral or IV Dexamethasone (Cannulation should only be carried out only when necessary to not further distress the child. If there is a risk of it precipitating respiratory arrest it should be performed where there are appropriate resuscitation facilities).

- Heliox

- If failing to maintain own airway, ventilatory support is required. Consider:

-

- Bag and Mask

- Nasopharyngeal airway

- Laryngeal mask

- Endotracheal Intubation

- Surgical intervention (e.g. Endoscopic aryepiglottoplasty aka supraglottoplasty). Tracheostomies in neonates are rarely required.

Prognosis / Complications

Prognosis is generally good and 99% will self-resolve with time. In rare cases requiring surgical intervention such as aryepiglottoplasty, the outcome is still good with rapid and lasting improvement in the vast majority of cases. Cases with a concurrent airway condition (e.g. subglottic stenosis, tracheomalacia) may have poorer outcomes.

References

- Ayari, S. et al. Pathophysiology and diagnostic approach to laryngomalacia in infants. European Annals of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Diseases. 2012(129), pp257-263.

- Ayari, S. et al. Management of laryngomalacia. European Annals of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Diseases. 2013(130), pp15-21.

- BMJ Best Practice. Laryngomalacia. 2020; Available at: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/754. Accessed 04/01/2021.

- Corbridge, R. and Steventon, N. 2009. Oxford Handbook of ENT and Head and Neck Surgery. Third Edition. Oxford University Publishing.

- Graham, J.M. et al. 2008. Paediatric ENT. Springer, Germany.

- Lee, K.J. 2012. Essential Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. Tenth Edition. McGraw-Hill,

- Hussain, S.M. 2016. Logan Turner’s Diseases of the Nose, Throat and Ear: Head and Neck Surgery. Eleventh Edition. CRC Press, Florida USA.

- Gleeson, M. et al. 2008. Scott-Brown’s Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery Volume 1. Seventh Edition. Hodder Arnold, UK.

Images

Laryngomalacia. Taken from:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Laryngomalacia.jpg (Public Domain)