Asthma is the commonest chronic condition in children. It is characterised by reversible and paroxysmal constriction of the airways, with airway occlusion by inflammatory exudate, and late airway remodelling.

In this article, we will discuss the epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical features, investigation and management of asthma in children.

Epidemiology

Asthma is the most common chronic condition in children, with 1 in 11 children in the UK affected. In children, it is associated with low levels of mortality and morbidity.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of asthma is exceptionally complex, poorly understood, and beyond the scope of this article. Here we give the basic principles that underpin the disease process, but some detail is omitted.

Asthma is a multi-factorial disease in which susceptible individuals have an exaggerated response to various stimuli. The disease process is driven by as vast array of mediators that lead to airway obstruction, and in more severe disease, airway remodelling.

Classical allergic asthma is driven by Th2 type T-cells. Allergens are presented to these cells by dendritic cells, which in these individuals leads to a disproportionate immune response.

The Th2 cells are activated by dendritic cells, and cytokines released from them result in the activation of the humoral immune system, with an increased proliferation of mast cells, eosinophils and dendritic cells as a result.

In turn, cytokines released by these cell contribute to the underlying inflammatory process and bronchoconstriction. One particular example of this is leukotriene C4, which is directly toxic to epithelial cells. Other mediators further exacerbate the situation by favouring the production of an exudate, such as the histamine released from mast cells.

Risk factors

- Genetic factors: There is no single gene, but various loci have been associated with asthma. As a result, asthma/atopy in parents or siblings is a risk factor.

- Environmental factors: Low birth weight, prematurity, parental smoking (note – ‘smoking outside the house’ does not eliminate the risk – many of the irritant chemicals in cigarette smoke are invisible and cling to parents’ clothing)

- Other: Viral bronchiolitis in early life, diagnosis of atopic dermatitis.

Precipitating factors

Exacerbations of asthma are initiated by stimuli known as precipitating factors.

- Cold air and exercise: Drying of the airways due to cold air and exercise leads to cell shrinkage, which triggers an inflammatory response.

- Atmospheric pollution

- Drugs:

- NSAIDs shunt the arachadonic acid pathway towards the production of leukotrienes, which are toxic to the epithelium.

- Beta-blockers prevent the bronchodilatory effect of catecholamines on the airways

- Exposure to allergens

Clinical features

The pattern of wheeze in an asthmatic is characteristic of the disease severity.

- Infrequent episodic wheezing: discrete episodes of wheeze lasting a few days with no interval symptoms (wheeze and cough free day and night).

- Frequent episodic wheeze: occur more frequently than infrequent (2-6 weekly).

- Persistent wheezing: wheeze and cough most days and may have disturbed nights.

Preschool wheeze

Wheezing is very common in preschool children; up to half of children will have had at least one significant episode of wheeze by their fifth birthday.

Most commonly this is caused by a viral infection of the respiratory tract, often due to the human rhinovirus or respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). The wheezing episode in this instance is normally preceded by coryzal symptoms.

Most preschoolers will outgrow their wheeze, however in up to 40% the wheeze persists into older childhood.

Two clinical patterns of preschool wheeze have been well documented:

- Episodic viral wheeze – wheezing only in response to viral infection and no interval symptoms.

- Multiple trigger wheeze – wheeze in response to viral infection but also to other triggers such as exposure to aeroallergens and exercise.

It is difficult to predict which preschoolers with a wheeze will later have a diagnosis of asthma.

History

A careful history is essential to ensure that symptoms are consistent with a diagnosis of asthma. Whilst asthma is the most common chronic condition in children, it is easy to under/mis/overdiagnose.

Important features that must be established include:

- Age at onset of symptoms

- Frequency of symptoms

- Severity of symptoms (how many days of school missed? Can the child do PE at school? Can they play with their friends without getting symptoms? Night time symptoms?)

- Previous treatments tried

- Any hospital attendances (A+E or admissions – including HDU/ITU admission – ventilated?

- Presence of food allergies

- Triggers for symptoms: Exercise, cold air, smoke, allergens, pets, damp housing

- Disease history: Viral infections, eczema, hay fever

- Family history of atopy

Examination

Clinical examination of children with asthma is almost always normal in between acute episodes. Clinical examination should look for the following:

- Finger clubbing (not suggestive of asthma, more suggestive of cystic fibrosis or bronchiectasis)

- Chest shape – a hyperinflated chest suggests poorly controlled asthma

- Chest symmetry

- Breath sounds

- Presence of crepitations (not suggestive of asthma)

- Presence of wheeze

- Examination of throat to assess for tonsillar enlargement: infectious cause?

Investigations

In primary care, investigations are rarely performed; asthma is a clinical diagnosis and has no single diagnostic test. If the clinical history and examination are consistent with asthma and there is no doubt in the diagnosis, investigations may not be needed. However, it can be useful to measure lung function as a baseline.

Spirometry

Usually normal in-between exacerbations, although there may be an obstructive pattern if poorly controlled (FEV1:FVC <70%). If an obstructive pattern exists, a reversal to normal after bronchodilators is highly suggestive of asthma.

Other

Peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) is a crude measure of respiratory function.

Bronchial provocation tests (histamine or metacholine) can be used in uncertain diagnoses, although they are not easy to interpret and require specialist input. Children with mild asthma (where diagnosis may be in doubt) will give negative results in 50% of cases.

Exercise testing is useful to assess whether there is exercise-induced symptoms

Skin prick testing or serum-specific IgE assays to allergens can be useful, but have limited role in diagnosis or management of asthma. Negative tests rules out an allergic sensitisation of airways to the allergen tested, although a positive result indicates only sensitivity and not necessary allergy.

Exhaled nitric oxide (ENO) testing may be performed. NO is produced in bronchial epithelial cells and its production is increased in those with Th2-driven eosinophilic inflammation. Those with asthma have raised ENO and it can be used to measure control. It is also raised in allergic rhinitis (hay fever).

Chest X-ray: in most children attending outpatient appointment a chest X-ray may be requested as it is useful to have a baseline CXR.

Other investigations which may be performed if there is doubt of a diagnosis of asthma or the child does not respond to asthma treatment:

- Oesopageal pH study to investigate for gastro-oesophageal reflux

- Bronchoscopy to exclude structural abnormality – also can collect tissue for biopsy (endochronical biopsy) or fluid (bronchoalveolar lavage)

- Chloride sweat test to exclude cystic fibrosis

- Nasal brush biopsy for ciliary evaluation to exclude primary ciliary dyskinesia

- Serum IgG, IgA and IgM and response to vaccinations (to exclude immunodeficiency)

- HRCT (high-resolution CT) to exclude bronchiectasis.

- Sputum culture

Management

Ongoing management

The overarching aim of managing asthma is to achieve good symptom control.

In children, this includes full school attendance, no sleep disturbance, <2/week daytime symptoms, no limitation on daily activities, no exacerbations, using salbutamol <2/week, and maintaining normal lung function.

Management is based on guidelines published and regularly reviewed by British Thoracic Society (BTS), Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN) and Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). GINA updated the guidelines for management of asthma in 2023³ and has included a new strategy called MART (Maintenance and Reliever Therapy) for children above age of 5, in which a single inhaler would act as both a reliever and maintenance. This was found to have better control of symptoms and to decrease exacerbation and hospitalisation. The management approach is ‘stepwise’ in that children move up to the next level of management if the current step is not controlling symptoms. The aim is to control all symptoms whilst being on the lowest treatment step possible.

Children ≤ 5 years

Step 1 – Intermittent short course of Low dose inhaled corticosteroids at onset of viral illness

Step 2 – Daily low dose ICS (inhaled corticosteroids)

Step 3 – Double ‘Low’ dose ICS

Step 4 – Continue ICS and refer to respiratory physician for assessment

Children 6-11 years

Step 1 – Low dose inhaled corticosteroids whenever SABA (short acting B2-agonist) is needed

Step 2 – Daily low dose ICS + as required SABA

Step 3 – Low dose ICS-LABA (long acting B2-agonist) OR medium dose ICS OR very low dose ICS-formoterol (MART)

Step 4 – Medium dose ICS-LABA OR low dose ICS-formoterol (MART)

-Refer to respiratory physician for assessment

Step 5 – High dose ICS-LABA

-Refer to respiratory physician for assessment

-Consider using other drugs such as monoclonal antibodies

Children >12 years

Step 1 – As required low dose ICS-formoterol

Step 2 – As required low dose ICS-formoterol

Step 3 – Low dose maintenance ICS-formoterol plus as required low dose ICS-formoterol

Step 4 – Medium dose maintenance ICS-formoterol plus as required low dose ICS-formoterol

Step 5 – Add on Long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) to step 4

-Refer to respiratory physician for assessment

-Consider using high dose ICS-formoterol

-Consider using other drugs such as monoclonal antibodies

Other drugs

If under the care of a respiratory paediatrician and control is not yet achieved despite high doses of inhaled corticosteroids with add-on therapy, some children may be prescribed a trial of biological agents.

1. Omalizumab is a monoclonal antibody for IgE and reduces free IgE in the blood. This reduces IgE mediated inflammatory response. It should only be given to children who have persistent poor control as described above and evidence of allergic sensitisation to a periennial aeroallegen (house dust mite) and a raised serum total IgE.

2. Mepolizumab is a monolonal antibody for IL-5, which binds to circulating IL-5 (cytokine) leading to death of eosinophils.

3. Dupilumab is a monoclonal antibody for IL-4, aiming to decrease cytokine release and reducing inflammation.

General management points

- Aerosol inhaler devices should always be used with a spacer device.

- Always ask the question of compliance. Are the symptoms not controlled because the child is not taking the treatment?

- Long-acting beta-2 agonists (e.g. salmeterol) should not be prescribed as a monotherapy inhaler and should be prescribed in combination with a corticosteroid.

- Steroid equivalency: fluticasone is twice as potent as beclometasone so if a child is on Seretide 125 inhaler 2 puffs BD (125mcg fluticasone per dose) the equivalent daily beclometaone dose is 1000mcg (125×4 = 500, x2 (twice as potent as beclometasone)).

- Asthma management plan: all children diagnosed with asthma should have a written asthma management plan.

- Inhaler technique should be reviewed by an asthma/practice nurse

Complications

Asthma exacerbation

An asthma attack has the potential to be life-threatening.

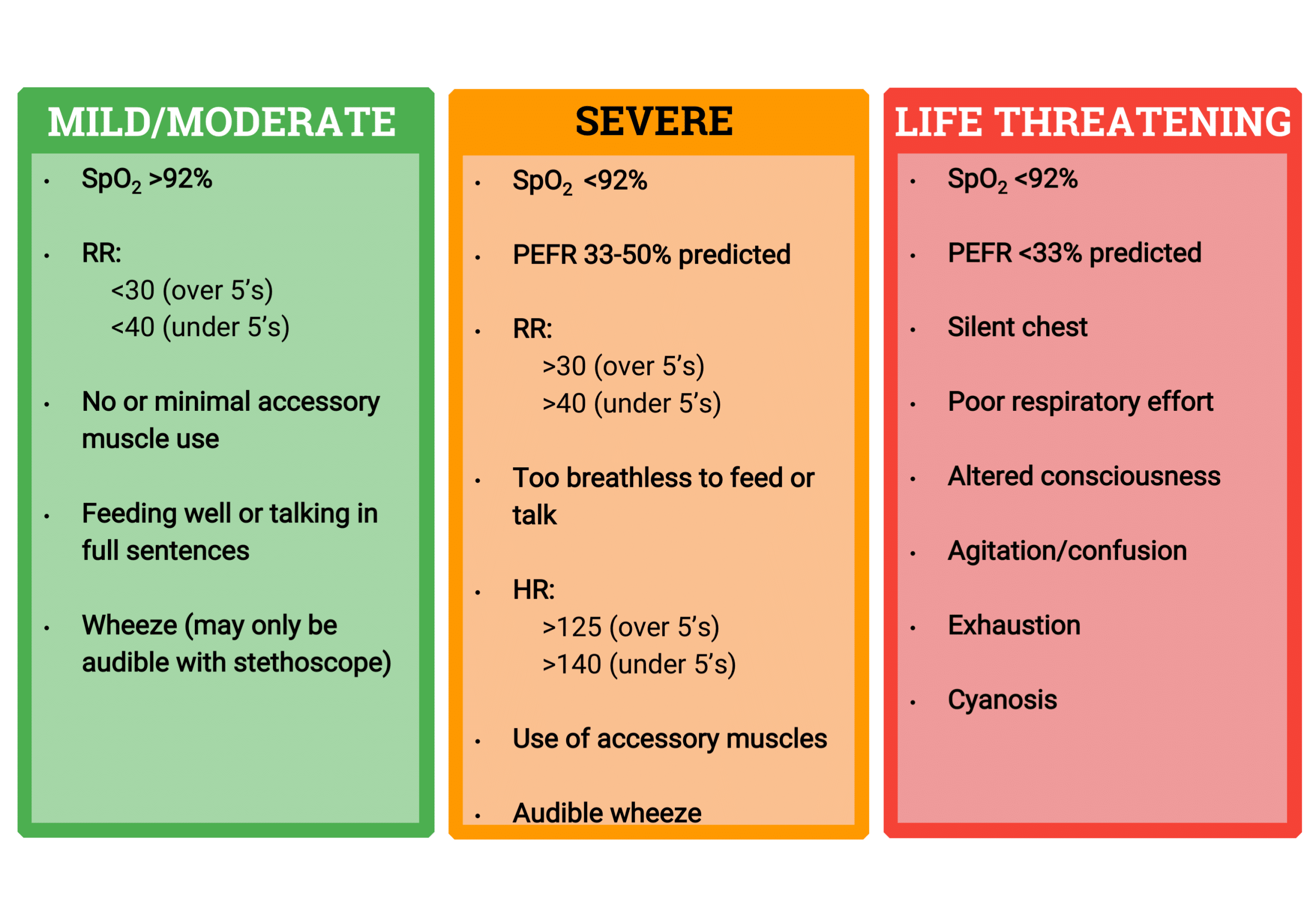

Clinical features (figure 1)

- Mild: SaO2 >92% in air, vocalising without difficulty, mild chest wall recession and moderate tachypnoea.

- Moderate: SaO2 <92%, breathless, moderate chest wall recession.

- Severe: SaO2 <92%, PEFR 33-50% best or predicted, cannot complete sentences in one breath or too breathless to talk/feed, heart rate >125 (over 5 years old) or >140 (2-5 years old), respiratory rate >30 (over 5 years) or >40 (2-5 years).

- Life-threatening: SaO2 <92%, PEFR <33% predicted, silent chest, poor respiratory effort, cyanosis, hypotension, exhaustion, confusion

Immediate management

- Oxygen: SaO2 <94% should receive high flow oxygen to maintain saturations between 94-98%.

- Bronchodilators: Inhaled SABA (salbutamol) – via nebuliser if severe. Inhaler and spacer device is as effective as nebuliser in children with mild/moderate asthma attack.

- Ipatropium bromide (anti-muscuranic) added in if no or poor response to inhaled SABA

- Corticosteroids: A short course (3 days) of oral prednisolone should be commenced. There is insufficient evidence to suggest that a single dose of oral dexamethasone has an advantage over a 3 day course of prednisolone but practically this may be the drug used. If the child vomits or is too unwell to take oral medication intravenous hydrocortisone should be used.

Second-line management

- Intravenous salbautamol can be considered with specialist input if there is no response to inhaled bronchodilators. It is essential to monitor for salbutamol toxicity.

- Magnesium sulphate can be considered, as it has an effect as a bronchodilator.

Safe-discharge criteria

- Bronchodilators are taken as inhaler device with spacer at intervals of 4-hourly or more (e.g. 6 puffs salbutamol via spacer every 4 hours). Previous practice involved weaning the amount or interval of bronchodilators over a few days but this practice does not have sufficient clinical evidence. As such, a chld should receive 6-10 puffs salbuatmol as required every 4 hours and seek medical help if symptoms are not controlled by this.

- SaO2 >94% in air

- Inhaler technique assessed/taught

- Written asthma management plan given and explained to parents

- GP should be notified of the admission within 24 hours of discharge and primary care follow up should be arranged within 2 working days

References

| (1) Hull, J., Forton, J., & Thomson, A. H. (2015). Paediatric respiratory medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press |

| (2) Lissauer, T., & Clayden, G. S. (2011). Illustrated textbook of paediatrics. Edinburgh: Mosby. · https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/document-library/clinical-information/asthma/btssign-asthma-guideline-quick-reference-guide-2014/ |

| (3) Levy, M.L., Bacharier, L.B., Bateman, E. et al. Key recommendations for primary care from the 2022 Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) update. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 33, 7 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-023-00330-1 |

| (4) Pocket guide for asthma management and prevention, updated 2023; GINA |