Bronchiectasis is the abnormal dilatation of the airways with associated destruction of bronchial tissue. It has been shown that bronchiectasis is potentially reversible, especially in children. It commonly occurs as a result of cystic fibrosis (CF) however there are distinct pathologies that lead to non-CF bronchiectasis and in this article we will focus on these. For more information regarding CF, please follow the link to our article on the subject.

In this article, we will discuss the pathophysiology, clinical features, management and complications of bronchietasis.

Epidemiology

In the UK, the estimated prevalence of non-CF bronchiectasis is 172/million children aged <15 years.

Pathophysiology

There are several aetiologies of non-CF bronchiectasis, which are categorised below. Generally, the inflammatory response to a severe infection leads to structural damage within the bronchial walls, which causes dilatation. Scarring, which arises as a consequence of the immune response, reduces the number of cilia within the bronchi. This predisposes the individual to further infections.

The causes of bronchiectasis given below are mostly either causative organisms of infection, or conditions that place the patient at increased risk of infection.

Post-infectious

A severe infection of the lower respiratory tract can lead to bronchial damage and bronchiectasis. The most typical organisms include:

- Streptococcus pneumonia

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Adenovirus

- Measles

- Influenza virus

- Bordetella pertussis

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Immunodeficiency

- Antibody defects: agammaglobulinaemia, common variable immune deficiency or IgA/IgG deficiency

- HIV infection

- Ataxia telangiectasia

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD)

This is an autosomal recessive genetic defect leading to either the reduced efficacy or complete inaction of bronchial cilia. Over 250 different genes are responsible for building the necessary proteins essential for ciliary function. PCD is rare, with an incidence of one in 150,000-300,000 births.

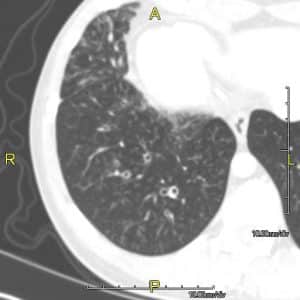

In the chest, this causes problems with mucociliary clearance leading to increased susceptibility to low-grade infections and irritation from foreign particulates. Figure 2 demonstrates a CT scan of a patient with PCD.

Figure 2: A CT scan of a patient with PCD showing mild bronchial wall thickening

Post-obstructive

- Foreign body aspiration

Congenital syndromes

- Young’s syndrome: A rare condition associated with bronchiectasis, reduced fertility and rhinosinusitis.

- Yellow-nail syndrome: Another rare syndrome associated with pleural effusions, lymphoedema and dystrophic nails. Bronchiectasis occurs in around 40% of patients.

Clinical Features

History

The key feature that should be elicited from the history is the presence of a chronic, productive cough. Otherwise, there may be no other key symptoms. However parents/children may complain of:

- Purulent sputum expectoration

- Chest pain

- Wheeze

- Breathlessness on exertion

- Haemoptysis

- Recurrent or persistent infections of the lower respiratory tract

Examination

Physical examination may be entirely normal but finger clubbing and/or inspiratory crackles may be elicited in children with bronchiectasis. Wheezing can also be heard on auscultation of the chest in some children.

Investigations

The purpose of investigation of children with suspected bronchiectasis is two-fold. Firstly, the diagnosis needs to be confirmed. Secondly, investigations looking for a cause should be carried out.

Imaging

- Chest X-ray may show bronchial wall thickening or airway dilatation. However it is important to note that a chest radiograph can appear completely normal in those with bronchiectasis.

- High resolution CT (HRCT) is the gold-standard investigation to diagnose bronchiectasis. Features indicative of the diagnosis are; bronchial wall thickening, diameter of bronchus larger than that of the accompanying bronchial artery (‘Signet ring’ sign) and visible peripheral bronchi.

- Different patterns seen on HRCT can occur with different aetiologies

- Bilateral upper lobe bronchiectasis is commoner in CF.

- Unilateral upper lobe bronchiectasis is commoner post-TB infection.

- Focal bronchiectasis (lower lobe) can be seen after foreign body inhalation.

Bronchoscopy

Bronchoscopy is not required to diagnose bronchiectasis and is not routinely performed in all children with the disease. It is reserved generally for children who have evidence of focal bronchiectasis evident on HRCT or when there is evidence of a possible airway abnormality.

Investigating the underlying cause

- A chloride sweat test must be performed to exclude CF. CFTR gene mutation analysis may also be helpful if the sweat test is borderline or there is a strong clinical suspicion of CF.

- Full blood count with leucocyte differential – assess lymphocyte and neutrophil counts.

- Immunoglobulin panel to assess for immunoglobulin deficiency.

- Specific antibody levels to vaccinations e.g. pneumococcal or Hib (Haemophilus influenzae B) vaccine.

- If bronchoscopy is performed a ciliary brush biopsy can be taken.

- HIV test

Microbiological assessment

This can be useful in the investigation of children with bronchiectasis as it can give an indication to the underlying cause, for example chronic Pseudomonas spp colonisation should prompt investigations for CF. It is important to understand which organisms are isolated in patients. Much like in CF, chronic bacterial infection can lead to declining lung function and aggressive courses of antibiotics may be needed to treat infection.

Lung function

Spirometry may be completely normal in mild disease. In advanced disease there can either be an obstructive pattern or a mixed obstructive and restrictive pattern, as severe scarring begins to compromise lung compliance.

Management

The aims of managing children with bronchiectasis are symptomatic relief, prevent progression of lung disease and to ensure normal growth and development.

Chest physiotherapy

Unlike CF, there are no clinical trials that demonstrate the benefit of performing chest physiotherapy in bronchiectasis. However, chest physiotherapy is a mainstay of treatment and children should see a chest physiotherapist to learn about mucus clearance techniques and should be encouraged to use them.

Exacerbations and antibiotics

- The most commonly isolated organisms include; non-encapsulated Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus penumoniae and Moraxella catarrhalis

- Antibiotic regimes depend on the clinical condition – some children will only need short courses at times of infective exacerbations and in between exacerbations expectorate only a little amount of sputum whereas others may need more continuous treatment with antibiotics

- Colonisation and infection with Pseudomonas spp. can occur in patients with non-CF bronchiectasis and in this instance Pseudomonas eradiation could be instigated, however there is little evidence to show the benefit of this in non-CF bronchiectasis

Other management

- Bronchodilators may be useful in patients who have wheeze. Bronchodilators may also be tried to aid expectoration of sputum prior to commencing chest physiotherapy

Follow-up

Children with bronchiectasis should be followed-up regularly and should have continual monitoring of their symptoms and lung function.

Complications

The complications of bronchiectasis include:

- Recurrent infection

- Life-threatening haemoptysis

- Lung abscess

- Pneumothorax

- Poor growth and development

Prognosis

The long-term prognosis is entirely dependent on the underlying cause. For example, in patients with post-infective disease, treatment should halt disease progression. In those children with more complex underlying pathology e.g. HIV infection, their prognosis depends heavily on the progression of the causative disease.

References

| (1) | Hull, J., Forton, J., & Thomson, A. H. (2015). Paediatric respiratory medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press |

| (2) | Lissauer, T., & Clayden, G. S. (2011). Illustrated textbook of paediatrics. Edinburgh: Mosby. |

| (3) | http://patient.info/doctor/bronchiectasis-pro |