Introduction

Sepsis is a dysregulated response to infection which may result in organ damage and death. Early features of sepsis are often non-specific and children with fever secondary to uncomplicated viral upper respiratory tract infections can look extremely unwell. It can be difficult to diagnose sepsis quickly and accurately.

Epidemiology

The precise epidemiology of sepsis is not known. However, infection is one of the commonest causes of death in children worldwide. Although widespread vaccination has reduced the prevalence of many infections, sepsis is still an important cause of morbidity and mortality in children. Increased recognition of sepsis as an entity in recent years means it is likely to be more common than previously thought.

A variety of pathogens can cause sepsis, including

- N. meningitides (meningococcus)

- Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus)

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Group A and B Streptococcus

- E. coli

Different pathogens are more common in different age groups. In a patient with new onset sepsis after a prolonged hospital stay, it is important to remember that hospital-acquired infections are likely to be with different organisms and thus empirical antibiotic choice would be different. Viral and fungal pathogens can more rarely lead to sepsis, with enteroviral infection mimicking sepsis in the neonatal period and fungal sepsis more common in the immunocompromised.

Pathophysiology

Sepsis is a pro-inflammatory cascade triggered by an infection which may rapidly lead to shock, organ dysfunction and death. Sepsis is usually defined as “systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) in the presence of infection”. Precise mechanisms are outwith the scope of this review.

Risk Factors & Clinical Features

History

Some groups of children are at particular risk of sepsis.

Neonates and young babies under 3 months of age are at increased risk of sepsis, particularly if they were premature or if there is a history of prolonged (>24 hours) rupture of membranes, maternal intrapartum pyrexia or maternal colonisation with Group B Streptococcus.

Immunocompromised children, such as those undergoing chemotherapy or taking immunomodulatory drugs for autoimmune disorders, immunodeficient or post transplant patients, are also at risk of rapidly becoming unwell with sepsis.

A history of fever is the most common symptom of any infection, including sepsis, but it is important to note that an absence of fever, and potentially hypothermia, may be seen in some of the most unwell patients, particularly the very young and those who are immunocompromised. Non-specific symptoms such as lethargy, nausea and vomiting, headache and abdominal pain also occur commonly.

History taking to determine the source of infection is important because it helps to localise the focus of infection, identify possible complications, assists in choosing targeted investigations, rationalisation antibiotic choice and duration of treatment.

Examination

Signs of shock (hypotension, tachycardia, cool peripheries, confusion) point to a diagnosis of severe sepsis with shock, but children often compensate well and only develop hypotension as a late sign. Tachycardia, conversely, often occurs in relatively well children with fever. Tachycardia which is disproportionate to the fever or which does not resolve when temperature settles is highly suggestive of serious infection and potential sepsis.

Signs of the source of infection, such as crackles on chest auscultation or an area of cellulitic skin, may be noted, but the absence of a clear focus does not exclude sepsis.

A non-blanching rash is suggestive of meningococcal disease (with or without meningitis) and any febrile child with non-blanching rash should be treated promptly with antibiotics and supportive care as required, however it is important to remember that the absence of rash does not exclude this diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis

An uncomplicated infection such as viral upper respiratory tract infection can mimic sepsis in children, who often become very tachycardic and look unwell when febrile. Persisting tachycardia, poor central capillary refill or hypotension suggest sepsis. If in doubt, it is safer to treat for sepsis and then rationalise treatment later. Observing a patient for a period of time may be useful as seeing whether they improve or deteriorate (particularly after giving antipyretics) can be very helpful in distinguishing sepsis from less severe infection.

Leukaemia and aplastic anaemia can present concurrently with sepsis and would usually be picked up on blood film. A child who is pale and with easy bruising or non-blanching rash may have a haematological disorder which predisposes them to develop sepsis. In these children, treating sepsis as well as the underlying disorder is essential.

Many other malignancies, particularly lymphoma as well as other extracranial solid tumours, can present with fever and an ill-looking child.

Autoimmune conditions such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis may also mimic infection and possible sepsis. There may also be a history of rash or swollen joints, but in systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis, fever may be the first symptom.

It is also essential to consider Kawasaki disease in children with prolonged fever. Other symptoms such as rash, conjunctivitis, cervical lymphadenopathy and cracked lips may well be present.

In all of these scenarios, consider prompt treatment with broad spectrum antibiotics until all investigation results are known.

Investigations

Laboratory tests

Raised inflammatory markers and positive cultures or PCRs may be obtained from a child with sepsis, but the diagnosis is a clinical one and these investigations are more useful in diagnosis of occult infection or locating a source of sepsis than in diagnosing sepsis itself. A blood gas may well show a metabolic acidosis with raised lactate, but this is a non-specific finding.

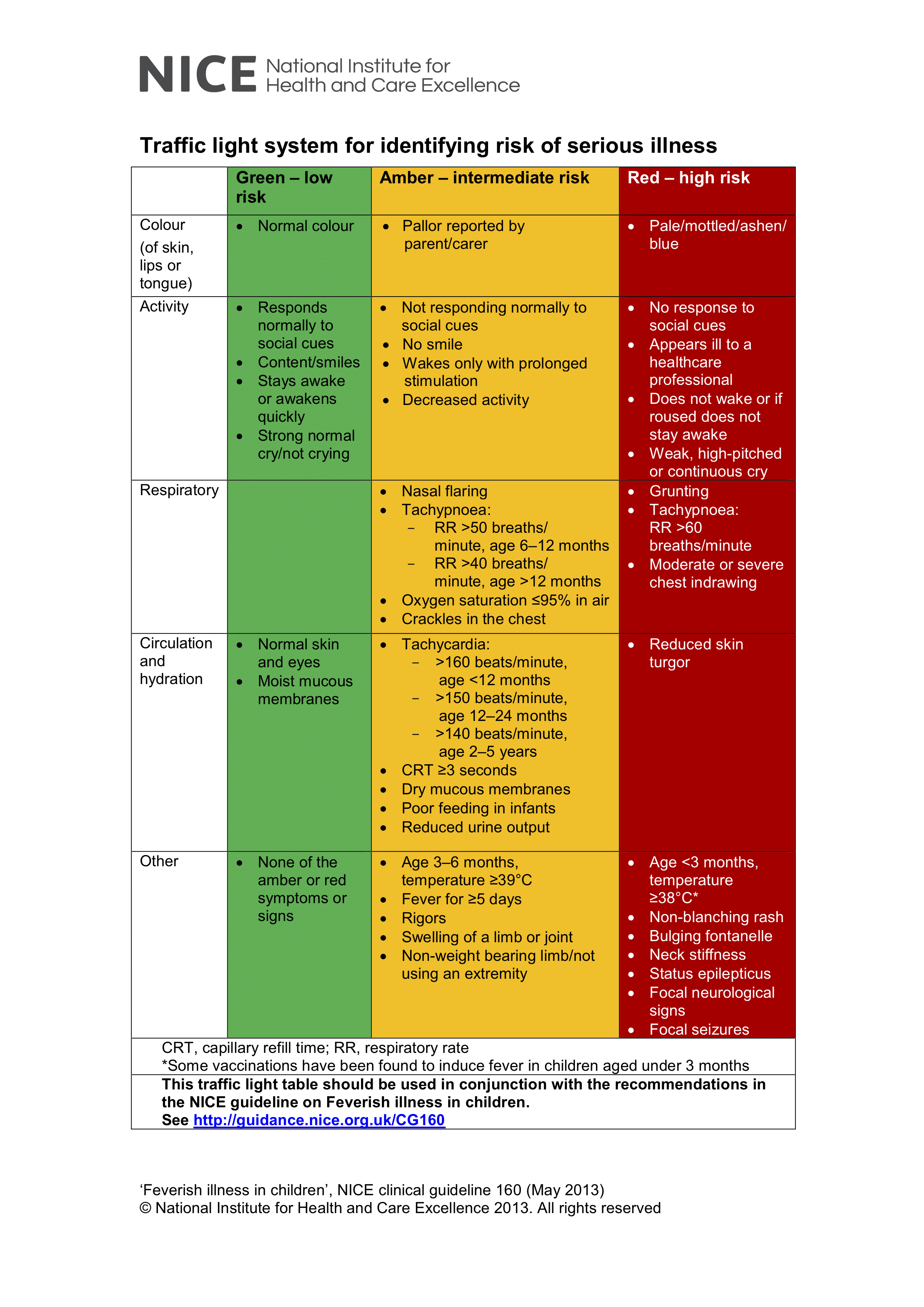

In babies under 3 months of age with fever, full blood count, CRP, blood culture and urine testing should be carried out. Stool culture should be taken if diarrhoea is present. These investigations should also be performed in all children under 5 with any “red” features, as per table 1 below3.

Imaging or invasive tests

Imaging such as chest X-ray and abdominal ultrasound and invasive tests such as lumbar puncture are helpful in finding the focus of infection but have no role in diagnosing sepsis.

In neonates, babies under 3 months of age who look unwell and/or those with white blood cell count greater than 15× 109/litre or less than 5 × 109/litre, a lumbar puncture should be performed, ideally before administration of antibiotics, unless the child is too unstable for this3. Chest X ray should be performed in infants under 3 months old only if chest signs are present3.

Risk scoring

NICE provide a “traffic light” scoring system for risk of serious illness in febrile children under the age of 5 years (Figure 1)3:

Figure 1: Risk of serious illness in febrile children under 5 years of age, taken from NICE guideline CG160: Fever in under 5s: assessment and initial management

Management

Initial management

In any child with suspected infection or any unwell neonate, sepsis should be considered. Any immediately life-threatening features should be identified and managed according to the principles discussed in the ‘Approach to the Seriously Unwell Child’ article.

The “sepsis 6” provides a useful way of remembering some key principles of management:

- Take blood cultures

- Check blood lactate

- Monitor urine output (with catheterisation if necessary)

- Give high flow oxygen

- IV/IO fluid

- IV/IO antibiotics

Children are particularly prone to hypoglycaemia when unwell and this should be promptly corrected with a 2ml/kg bolus of 10% dextrose if blood sugar is <3mmol/L.

The Meningitis Research Foundation provide a useful table detailing the initial management of children with suspect meningococcal disease, which is broadly applicable to sepsis from other pathogens and can be found at the back of the booklet “Lessons from research for doctors in training: recognition and early management of meningococcal disease in children and young people” which can be downloaded from: https://www.meningitis.org/healthcare-professionals/resources

Definitive and long-term management

Definitive management centres on appropriate treatment of the underlying infection. However, supportive care is likely to be required whilst antimicrobial therapy takes effect. In some cases, this may involve intensive care admission for ventilator or inotropic support.

Complications and prognosis

Prognosis of sepsis is linked to speed of recognition and prompt antibiotic administration.

The majority of children with sepsis will survive, but a number will have significant complications. Any children with a diagnosis of bacterial meningitis should be followed up to assess for long-term developmental delay, and audiological testing should be arranged on discharge. Limb ischaemia may lead to amputations, particularly in severe meningococcal disease, and these children will require significant support from orthotic, physiotherapy and occupational therapy colleagues.

References

This article contains information based on the NICE guidelines NG51: Sepsis: recognition, diagnosis and early management1, CG102: Meningitis (bacterial) and meningococcal septicaemia in under 16s: recognition, diagnosis and management2 and CG160: Fever in under 5s: assessment and initial management3.

| 1. | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2016) NICE guideline NG51. Sepsis: recognition, diagnosis and early management. |

| 2. | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2015) NICE guideines CG102: Meningitis (bacterial) and meningococcal septicaemia in under 16s: recognition, diagnosis and management. |

| 3. | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2017) NICE guideline CG160: Fever in under 5s: assessment and initial management. |