Introduction

Advancement in therapies has led to drastically improved survival for malignant diseases. Consequently, medical professionals are more likely to encounter long-term malignancies and therapy related complications. This article provides an overview of the common oncological emergencies in the paediatric population.

Superior Vena Cava (SVC) Syndrome

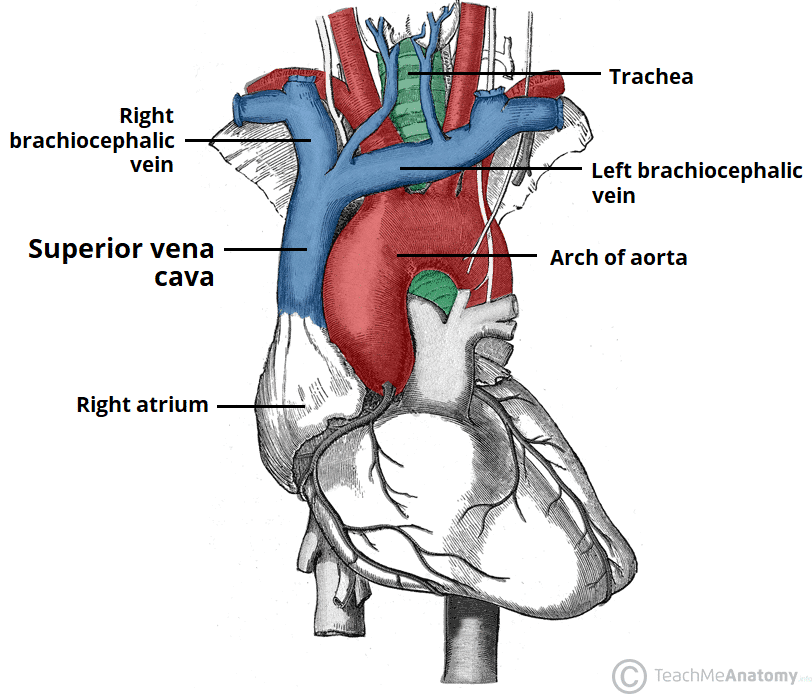

SVC syndrome results from the compression or obstruction of major vessels. It is a rare, life-threatening emergency requiring early recognition and prompt treatment. In the paediatric population, anterior mediastinal masses secondary to lymphomas and leukaemias are the most common oncological causes of SVC syndrome.1 SVC syndrome can also result from thrombosis, most commonly due to central venous catheterisation.

Fig. 1 Superior vena cava feeding into the right atrium

Obstruction of the superior vena cava causes:

- reduced venous return from the head and neck to the heart

- direct airway compression restricting total lung capacity2

Presentation

Clinical presentation can be acute or insidious depending on the growth rate of the mass and the presence of a collateral circulation shunting blood to the heart.

Obstruction of blood flow causes:

- face and neck oedema

- distention of neck and thoracic veins

- plethora

- headaches

- dizziness

Direct compression of the airway presents as:

- dyspnoea

- hoarse voice

- cough

- oropharyngeal obstruction

- orthopnoea

Investigations3

- CXR – look for signs of mediastinal widening, pleural effusion

- CT chest – unless patient clinically unstable

- ECHO – look for signs of pericardial effusion and assess cardiac function

- Baseline bloods – FBC, Blood film, U+Es, lactate dehydrogenase

Management

Begin with a thorough ABCDE assessment and early discussion with haematology and oncology consultants. Avoid giving fluid via a cannula in the upper limbs.

Spinal cord compression

Malignant spinal cord compression (SCC) can lead to permanent loss of sensory, motor and/or autonomic function in children. It is commonly an acute complication of metastatic sequalae of a known malignancy however, it can also be the presenting symptom of an undiagnosed cancer. Children most at risk of SCC are those with a diagnosis of sarcoma, neuroblastoma, lymphoma, and leukaemia.4

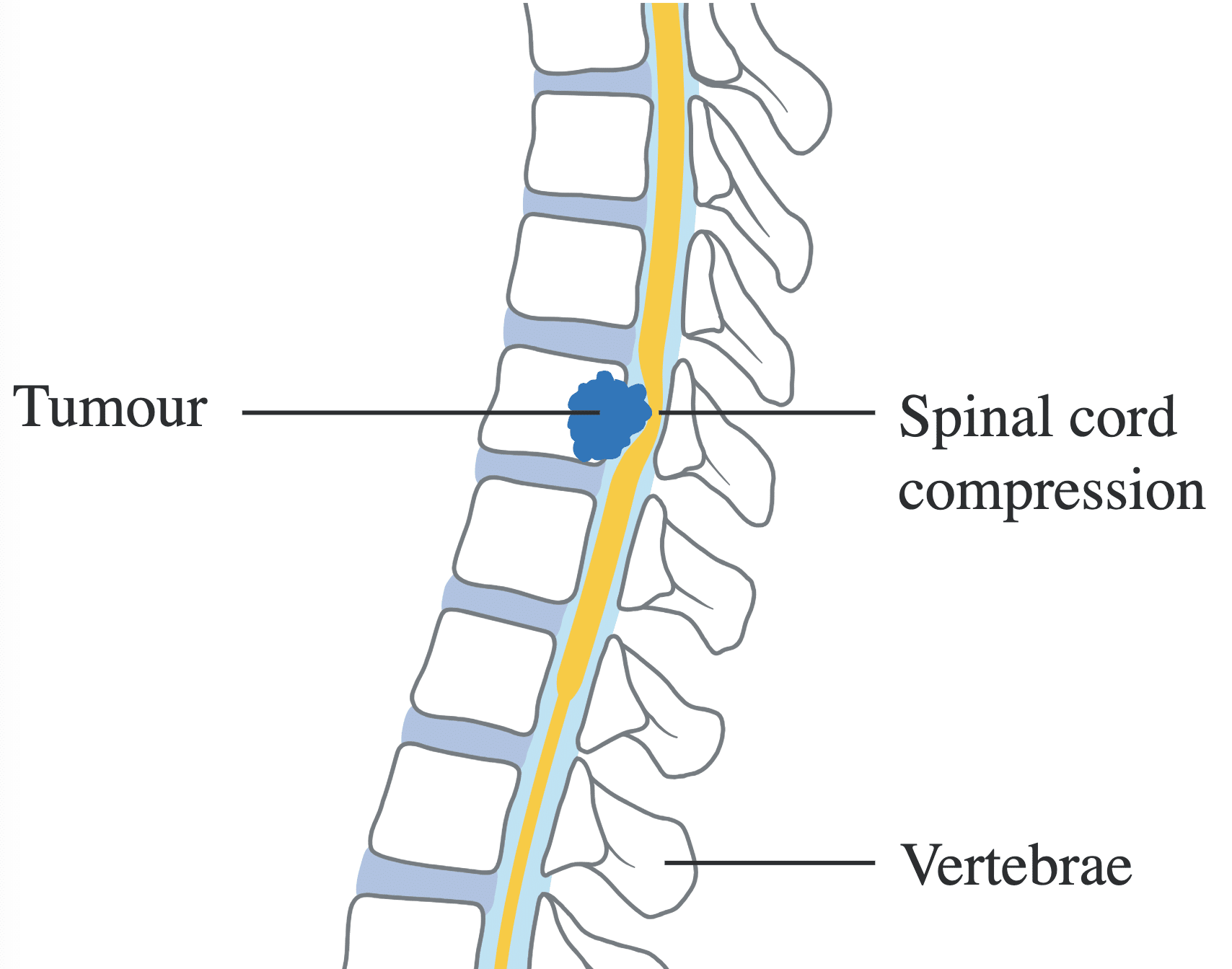

SCC can occur due to

- Tumour extension through the vertebral foramina into the epidural space (most common)

- Intradural metastases

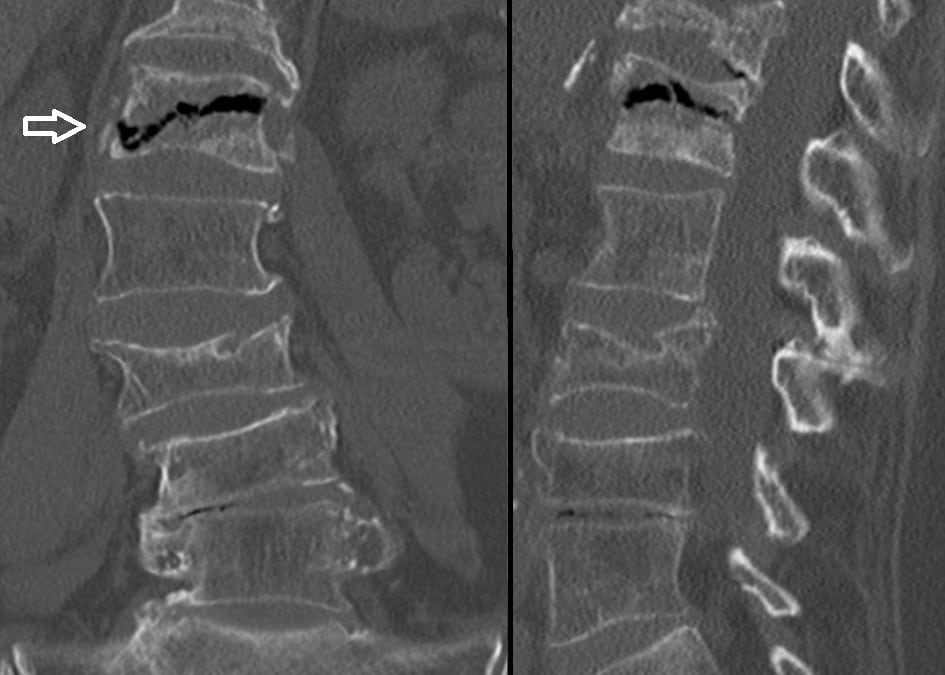

- Crush fractures from bony vertebral metastases or extended steroid use

Fig. 2 Diagram showing spinal cord compression by a direct extension of a tumour

Fig. 3 CT image showing intravertebral vacuum cleft sign of spinal cord compression

Presentation & Investigation5

MRI spine is the gold standard imaging modality and is indicated by the following clinical signs:

- Unexplained, persistent back pain which wakes the child from sleep, restricts movement and/or does not resolve with simple analgesia

- Limb weakness/paraesthesia

- Progressive weakness below the level of the suspected lesion

- Bladder dysfunction/incontinence

- Constipation or overflow diarrhoea

Management4

Early discussion with oncology/haematology consultants as well as neurosurgical involvement is crucial.

Surgical

- Keep nil by mouth

- Catheterisation – for urinary incontinence

- Cord decompression – with surgery, chemotherapy or localised radiotherapy

Medical

- Dexamethasone – reduces cord oedema

- Analgesia – opiates or neuropathic pain relief

- Laxatives – to manage constipation

Tumour lysis syndrome (TLS)

TLS is an oncological emergency characterised by overwhelming cell lysis. This causes mass release of intracellular cell content into the circulation resulting in the stereotypical metabolic abnormalities. In paediatrics, children suffering with tumours such as acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma or other high proliferative malignancies with rapid cell turnover or high tumour burden are at risk of TLS. It is also commonly seen after the initiation of chemotherapy as well as spontaneously or perioperatively.1,6

Presentation7

Children with TLS present with signs and symptoms resulting from its characteristic metabolic abnormalities.

| Biochemical abnormality | Signs and symptoms |

| Hyperuricaemia

|

Oliguria or anuria, crystal formation in urine, hypertension, renal insufficiency |

| Hyperkalaemia

|

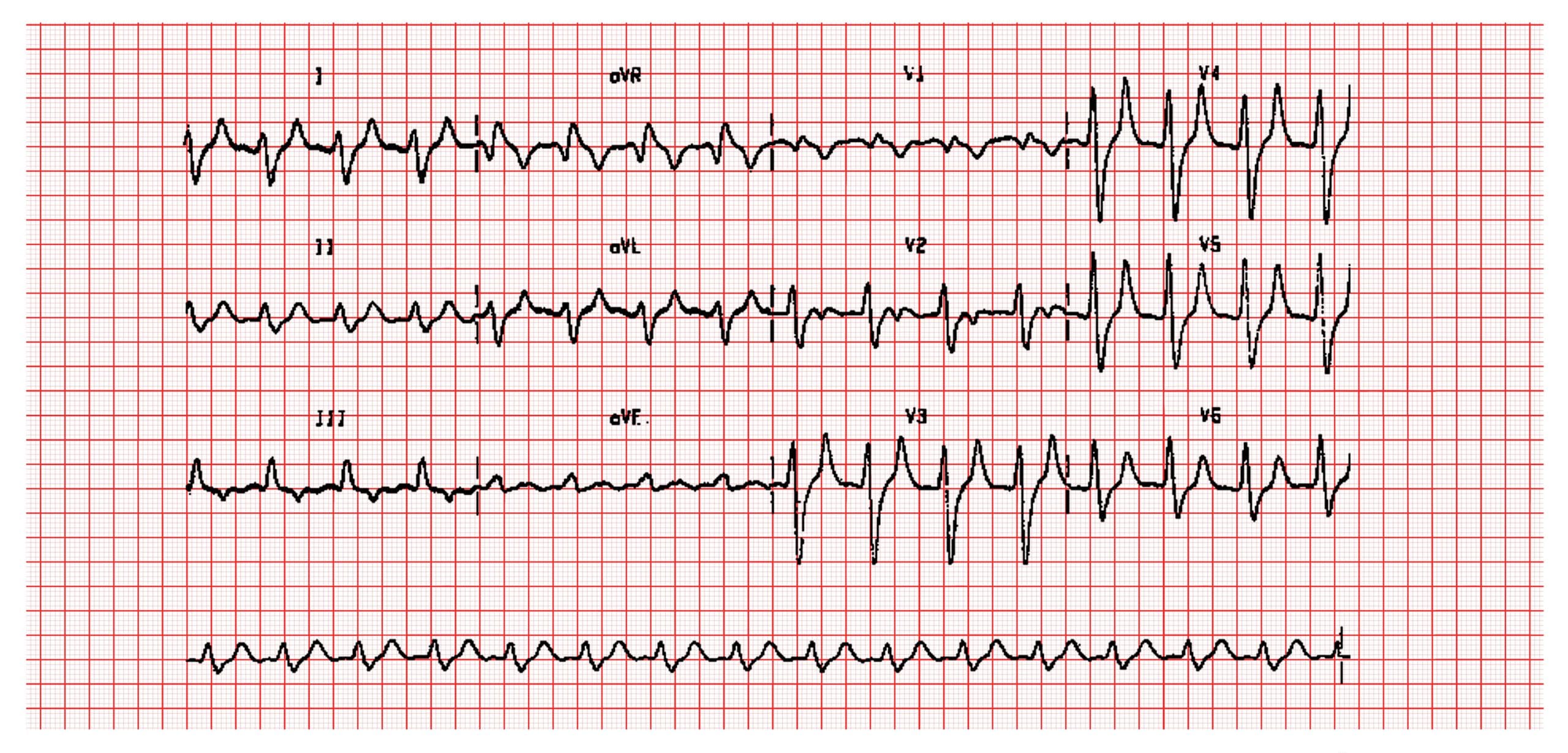

Nausea, slow/irregular pulse, muscle weakness, cardiac arrythmias, ECG abnormalities |

| Hyperphosphataemia

|

No obvious clinical signs |

| Hypocalcaemia

|

Muscle cramps, facial twitch, paraesthesia, seizures, ECG abnormalities |

Fig. 4 ECG in hyperkalaemia showing classic signs of reduced P waves and tented T waves

Investigations

- Bloods – U&Es, bone profile, FBC, urate

- Fluid balance – strict input/output charts

- Daily weight

Management8

The key in managing TLS is recognising those at risk to allow preventative measures to be placed. There are various criteria used to stratify patients into low, medium and high-risk categories but they are all based on similar general principles:

- evidence of TLS at diagnosis

- high risk tumour (e.g. ALL, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma)

- presence of pre-existing factors which can influence risk (e.g. acute kidney injury).

Prevention

- Allopurinol

- Used to manage hyperuricaemia

- Xanthinine oxidase inhibitor

- Prevents uric acid crystal production in the renal tubules however does not disintegrate existing deposits of uric acid.

Treatment

- Hyperhydration

- Introduce a strict hydration and fluid balance regimen to maintain a high urine output. No added potassium unless specifically directed by consultant.

- Aims to prevent uric acid crystallisation and calcium phosphate deposition in the renal tubules, thereby preventing renal function decline.

- Urine output must be 75-80% input (400 ml/m2/4 hours)

- Rasburicase

- Recombinant urate oxidase

- Acts to metabolise urate into allantoin, a more soluble compound

- Can act on uric acid deposits and reduce urate levels significantly

- Dialysis or haemofiltration

- Indicated by rising creatinine and phosphate with falling calcium and urine output

- Inform consultant immediately if this occurs

Febrile neutropenia

One of the most prevalent complications of cancer treatment is fever and neutropenia. Fever defined as a single temperature of on one occasion. Neutropenia is characterised as an absolute neutrophil count of <0.5 x109/L9.

History10

Remember to ask about the following risk factors that may predispose to febrile neutropenia

- The diagnosis

- Most recent blood test results

- Recent chemotherapy treatment

- Bone marrow suppression

- Symptoms relating to central line usage. Shaking chills/rigors/temp >39.5 C associated within an hour of a line manipulation is strongly suggestive of a line infection.

- Previous isolation of gram-negative bacteria

- Recent treatment with antimicrobial therapy or increased dosage in prophylactic therapy (may mask symptoms)

Fig. 5 Photograph of central venous line at R side of the neck with no infective features visible

Examination10

Patients presenting with a temperature require a focused examination to look for a source including:

- Oropharynx – consider mucositis, hepatic stomatitis, candidiasis

- ENT – take viral nasopharyngeal and throat swabs for extended viral screen.

- Upper gastrointestinal – painful swallowing may suggest herpetic or candidal oesophagitis.

- Abdominal – signs of colitis or typhlitis (caecal inflammation causing tenderness of the right lower quadrant)

- Perineum – always ask about perianal discomfort

- Central venous line sites – examine for erythema, swelling, tenderness or tracking along the line site

- Skin exam – look for rashes, examine bone marrow aspirate sites

Fig. 6 Photograph of oral candidiasis

Investigations

- Bloods – FBC, U+Es, CRP, venous blood gas, lactate

- Blood cultures

- Urine/Stool culture

- Sputum culture

- Imaging – chest and/or abdominal x-ray or CT

- Swab – nasal/throat/skin

Management11

- Initiate empirical antibiotics within 1 hour of arrival. First line antibiotic is Piperacillin/tazobactam (tazocin) +/- gentamicin +/- teicoplanin.

- Optimise antimicrobial once source of infection is identified or highly suspected.

- Daily examination for infective focus

- Repeat cultures if patient deteriorates clinically or remains febrile for a prolonged duration

References

- Prusakowski, M. K. & Cannone, D. Pediatric oncologic emergencies. Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am. 32, 527–548 (2014).

- Nossair, F. et al. Pediatric superior vena cava syndrome: An evidence-based systematic review of the literature. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 65, 1–8 (2018).

- Lewis, S. Clinical Guideline: Superior Vena Cava Obstruction. Bristol Royal Hospital for Children (2019). doi:10.3181/00379727-30-6458

- Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS. Management of Suspected Spinal Cord Compression in Children and Young People with Malignancy. (2015).

- Laughton, S. Cord Compression in the Oncology Patient. Starship (2016). Available at: https://starship.org.nz/guidelines/cord-compression-in-the-oncology-patient/.

- Zonfrillo, M. R. Management of Pediatric Tumor Lysis Syndrome in the Emergency Department. Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am. 27, 497–504 (2009).

- Cheung, W. L., Hon, K. L., Fung, C. M. & Leung, A. K. C. Tumor lysis syndrome in childhood malignancies. Drugs Context 9, 1–14 (2020).

- Jones, G. L. et al. Guidelines for the management of tumour lysis syndrome in adults and children with haematological malignancies on behalf of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Br. J. Haematol. 169, 661–671 (2015).

- NHSGGC. Management of neutropenia & fever: antibiotic policy. (2021). Available at: https://www.clinicalguidelines.scot.nhs.uk/nhsggc-guidelines/nhsggc-guidelines/infectious-disease/management-of-neutropenia-fever-antibiotic-policy/#bestpractice.

- The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. Fever and suspected or confirmed neutropenia. (2022). Available at: https://www.rch.org.au/clinicalguide/guideline_index/Fever_and_suspected_or_confirmed_neutropenia/. (Accessed: 30th November 2022)

- Dr Mary, M., Dr Sanjay, P., Prof Juliet, G., Ms Claire, F. & Dr Amy, M. Wessex Paediatric Oncology Supportive Care Guidelines : Management of Febrile Neutropenia. (2016).