Introduction

Acute epiglottitis is an acute, life-threatening condition, most commonly caused by infection. This article will look at the epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical features, differential diagnoses, investigations and management of epiglottitis.

Epidemiology

Epiglottitis is rare, only affecting approximately 1-4/100,000 people (4,7). The number of children presenting with acute epiglottitis has reduced significantly since the introduction of the Haemophilus influenza B (Hib) vaccine in 1985 (not introduced into routine screening programme in the UK until 1992 (9)) The average age of presentation has increased from 3.5 pre-vaccine to 14.6 post-vaccine(5).

Pathophysiology

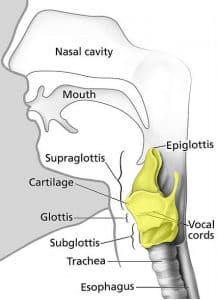

The epiglottis is a flap of cartilage behind the tongue, designed to protect the larynx during swallowing (Fig 1).

Fig 1: Anatomical position of the larynx (yellow) in the neck. It is continuous with the trachea inferiorly and the pharynx superiorly. The epiglottis can be seen superior to the larynx.

Haemophilus influenzae and streptococcus pneumoniae are commensal bacteria which may locally invade the epiglottis, resulting in inflammation in 75-90% of cases (6). Rarely, epiglottitis may be due to non-infectious causes such as trauma or thermal/chemical damage. Inflammation starts on the lingual surface of the epiglottis, before rapidly spreading to other laryngeal structures including the aryepiglottic folds, the arytenoids and supraglottic larynx. The vocal cords have a tightly bound epithelium which restricts progression of the swelling, increasing pressure in a small area and consequently causing airway obstruction. (3)

Children are at higher risk of acute airway obstruction because of their anatomy. Compared with adults, the epiglottis is much more floppy, broader, longer and angled more obliquely to the trachea (9). Additionally, their larger tongue and anteriorly-angled vocal cords mean children find it more difficult to move air past even a partial obstruction. (5)

Aetiology (1)

Infectious causes of epiglottitis are more common that non-infectious causes, though both are listed below. As already discussed, Haemophilus influenza type B used to be by far the most common cause of epiglottitis amongst children, accounting for 75-90% of cases (6). Bacteria still predominate in the list of causes, with the majority post the introduction of the HiB vaccine being caused by streptococcus species (1,7). Viruses have been implicated, though are less common, and can encourage a superimposed bacteria to invade and cause epiglottitis. (1, 12)

Bacterial

- Haemophilus influenza type B

- Streptococcus pneumonia

- Group A + C streptococci

- Staph aureus

- Moraxella cattarhalis

- Haemophilus parainfluenzae

- Neisseria meningitides

- Pseudomonas species

- Klebsiella pneumonias

- Pateurella multocida

Candida and aspergillus species in immunocompromised patients (1)

Viral infection

- HSV

- Parainfluenza

- VZV

- HIV

- EBV

Non-infectious

- Thermal injury e.g. steam, crack cocaine smoking

- Direct trauma e.g. blind sweep to remove foreign body

- Caustic insults e.g. ingesting dishwasher pellets

Risk Factors

- Children not receiving the HiB vaccine(10). Vaccinations must be delivered on time at 8, 12, 16 weeks and 1 year in order to receive the full protection (2). For an up to date list of the UK immunisation schedule, please visit this page: UK immunisations

- Male gender

- Immunosuppression (10)

Clinical Features

Remember the 4 D’s! (8)

- Dyspnoea

- Dysphagia

- Drooling

- Dysphonia (muffled “hot potato” voice in 54% (4))

Symptom duration is usually less than 12 hours and there is typically no cough. Children will appear toxic with a high-grade fever, sore throat, dehydration and may already have signs of partial airway obstruction. Stridor is a late sign. Some children may adopt a Tripod Position; the patient leans forward on outstretched arms with neck extended and the tongue out (in an attempt to position inflamed structures away from blocking the airway(4))

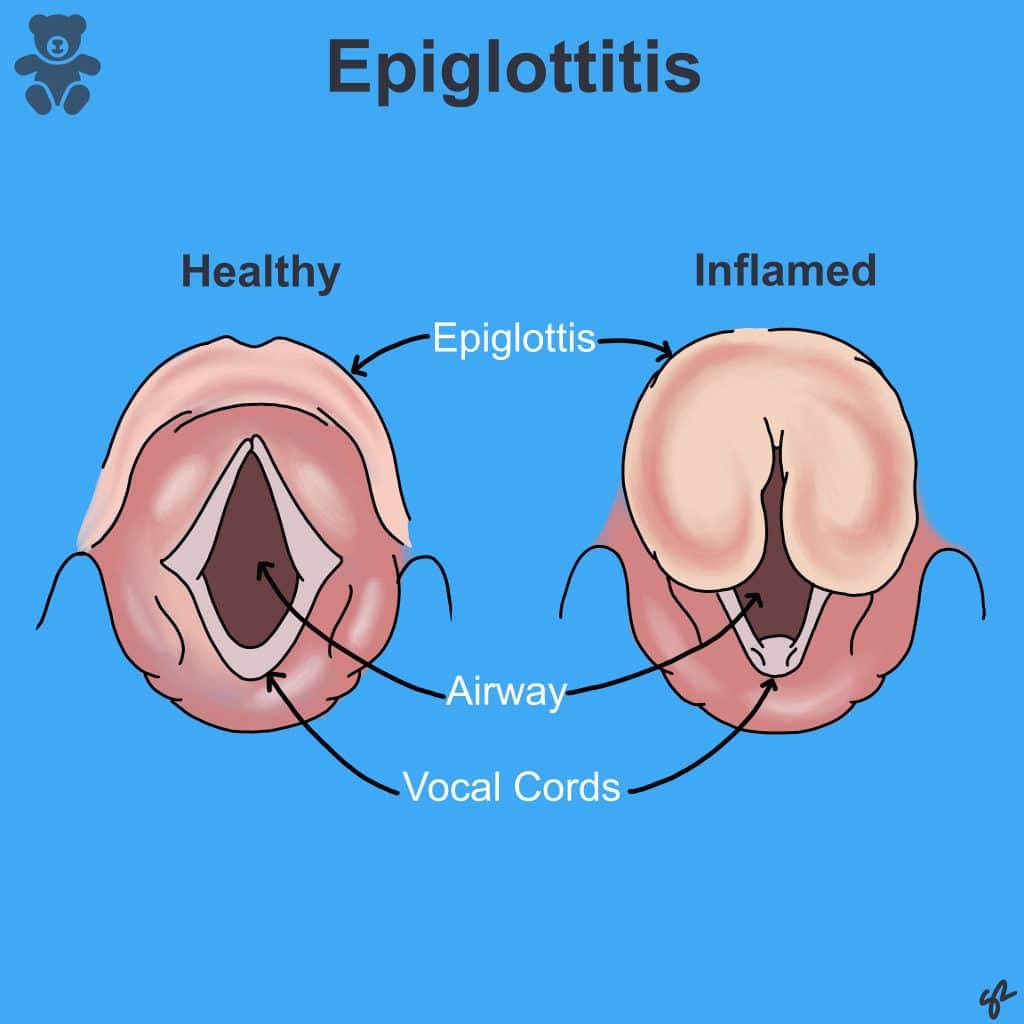

The epiglottis becomes inflamed, impeding on the airway and narrowing it (Fig 2).

Differential Diagnoses (12)

Differentials

Laryngotracheobronchitis (Croup)

- Distinctive, seal-like barking cough

- May have drooling, stridor and tripod position

- May have a prodrome of non-specific viral URTI symptoms

- Neck X-Ray: Steeple sign of subglottis

Inhaled foreign body

- History: Sudden onset e.g. whilst eating/playing with small toys

- No fever initially

- Neck X-Ray: May see radio-opaque foreign bodies (Not: Button battery is TIME CRITICAL EMERGENCY)

Retropharyngeal abscess

- Clinical features very similar (immediate management is the same as epiglottitis)

- CT: Abscess

- Laryngoscopy/Flexible Nasendoscopy: Normal epiglottis, swollen retropharyngeal space

Tonsillitis

- Bilateral erythematous tonsils with exudate (if bacterial)

- Longer clinical history

Peritonsillar Abscess

- Unilaterally displaced tonsil with peritonsillar erythema and swelling

- Deviated uvula

- CT: Collection of fluid with enhanced rim

Diphtheria

- Thick membrane over posterior pharynx

- Unvaccinated child

- Corynebacterium diphtheria found on microbiology assay

Check out our other articles on croup, tonsillitis and peritonsillar abscess for more information.

Investigations

The airway must be secured before considering further investigation. Children with epiglottitis have a high risk of obstructing their airway if agitated so shouldn’t be examined or undergo unnecessary observations which could exacerbate this. (11) It is important to keep the environment calm, allow the child to remain with their parent, avoid the supine position and aim to visualise the epiglottis in theatre(8). Intubation equipment should always be nearby as these children are prone to acute deterioration (5)

Throat Swabs: Both bacterial and viral swabs should be taken on intubation to aid diagnosis and guide management. (11)

Blood Tests: FBC, cultures and CRP (once airway secured) (9)

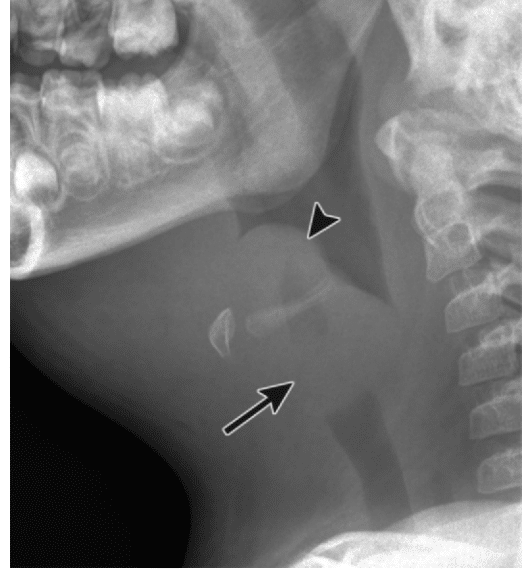

Lateral Neck X-Ray (Fig 3):

1) Thumb-Print Sign (swollen epiglottis) (5)

2) Thickened aryepiglottic folds

3) Increased opacity of the larynx and vocal cords

X-Rays can help rule out epiglottitis if a normal epiglottis is visualised, but should not waste time in a critical situation (11).

Fig 3: Lateral x-ray demonstrating the thumb-print sign associated with a swollen epiglottis

CT/MRI: This should only be completed once the airway is secured if the patient is not responding to initial therapy.

DO NOT SEND A PATIENT FOR IMAGING IF THERE IS A SUSPICION OF AIRWAY COMPROMISE

Management

-

Secure the Airway:

- Early escalation to the on-call anaesthetist.

- Early escalation to the on-call ENT registrar.

- Avoid exacerbating distress in the meantime.

-

Oxygen

- Parent can hold the mask near the child’s face.

-

Nebulised Adrenaline

- Bridging therapy whilst awaiting definitive airway management by reducing oedema of the upper airway mucosa (11).

-

IV Antibiotics

- 3rd Generation cephalosporins which cover for haemophilus influenza (e.g. cefotaxime/ceftriaxone (or as per local guidelines) (11, 13). Once stable and extubated, the child can be converted to oral antibiotics e.g. co-amoxiclav (11)

-

IV Steroids

- The benefit of steroids has not been proven in any studies but is often used to reduce supraglottic inflammation (12)

-

IVI

- Resuscitation and maintenance. Patients should remain nil by mouth until the airway has improved.

Complications and Prognosis

- Mediastinitis: If infection spreads to the retropharyngeal space (rare but severe with 50 % mortality)

- Deep Neck Space Infection: Retropharyngeal or Parapharyngeal cellulitis/abscess

- Pneumonia: Especially following intubation

- Meningitis: Complication in any haemophilus influenza type B infection

- Sepsis/Bacteraemia

Epiglottitis is a serious condition and early recognition is essential to prevent airway compromise. Maintain a high index of suspicion and do not try to confirm the diagnosis on your own. Groups with highest morbidity include infants <1y and adults >85y(4). However, with reduced cases and improved awareness, deaths are rare (1 in 100 cases)(2).

References

| No. | Reference |

| 1. | Patient UK. Epiglottitis. 2015; Available at: https://patient.info/doctor/epiglottitis-pro. Accessed 12/05/2020. |

| 2. | Nhs.uk. Epiglottitis. 2018. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/Epiglottitis. Accessed 12/05/2020. |

| 3. | Uptodate.com. Epiglottitis (supraglottitis): Clinical features and diagnosis. 2019. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epiglottitis-supraglottitis-clinical-features-and-diagnosis. Accessed 12/05/2020. |

| 4. | Pediatric Epiglottitis. 2016. Available at: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/963773-overview#a2. Accessed 12/05/2020. |

| 5. | Darras, KE, Roston, AT and Yewchuk, LK. 2015 Oct. Imaging Acute Airway Obstruction in Infants and Children. Radiographics. 35(7):2064-79. |

| 6. | Shah, RK, Roberson, DW and Jones, DT. 2004 Mar. Epiglottitis in the Hemophilus influenzae type B vaccine era: changing trends. Laryngoscope. 114(3):557-60. |

| 7. | Hermansen, MN, Schmidt, JH, Krug, AH, Larsen, K and Kristensen, S. 2014 Apr. Low incidence of children with acute epiglottis after introduction of vaccination. Danish Medical Journal. 61(4):A4788. |

| 8. | Guerra AM and Waseem M. Epiglottitis. [Updated 2019 Dec 16]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430960. |

| 9. | Public Health England. Revised recommendations for the prevention of secondary Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) disease. 2013; Accessed 12/05/2020 |

| 10. | Mayo clinic. Epiglottitis. 2018. Available at: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/epiglottitis/symptoms-causes/syc-20372227. Accessed 12/05/2020 |

| 11. | Beattie, M and Champion,M. 2012, Essential revision notes in paediatrics for MRCPCH, 3rd edition, PasTest, Cheshire. |

| 12. | BMJ Best Practice. Epiglottitis. 2018. Available at: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-us/452. Accessed 12/05/2020. |

| 13. | Paediatric Formulary Committee. BNF for Children (online) London: BMJ Group, Pharmaceutical Press, and RCPCH Publications. Available at: http://www.medicinescomplete.com. Accessed on 12/05/2020. |