Epidemiology

Pyloric stenosis occurs in 1 in 500-1000 live births, affecting 4 males for every 1 female1.

Pathophysiology

Pyloric stenosis is characterised by progressive hypertrophy of the pyloric muscle, causing gastric outlet obstruction2. The aetiology remains unknown2.

Risk Factors

The primary risk factors are male gender and a family history of pyloric stenosis3.

Clinical Features

Pyloric stenosis presents at around 4-6 weeks of age with non-bilious vomiting after every feed3. Vomiting is very forceful, and is typically described as projectile2. Despite this, babies will continue to feed hungrily. Haematemesis has also been reported. Weight loss and dehydration are very common at presentation3, ranging from mild dehydration to hypovolaemic shock.

On examination, there may be visible peristalsis and a palpable olive-sized pyloric mass, best felt during a feed3 (see below).

Differential Diagnosis

- Gastroenteritis

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux, including Sandifer syndrome

- Over-feeding

- Sepsis

- UTI

- Food allergy

If bilious vomiting is reported, don’t forget to think malrotation!

Investigations

A test feed should be performed with a NG tube in situ and the stomach aspirated. Whilst the child is feeding, the examiner should palpate for a pyloric mass and observe for visible peristalsis.

Ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice4. An ultrasound of the abdomen will demonstrate hypertrophy of the pyloric muscle, with wall thickness >3mm, length >15mm and diameter >11mm5. See https://radiopaedia.org/cases/pyloric-stenosis for useful images.

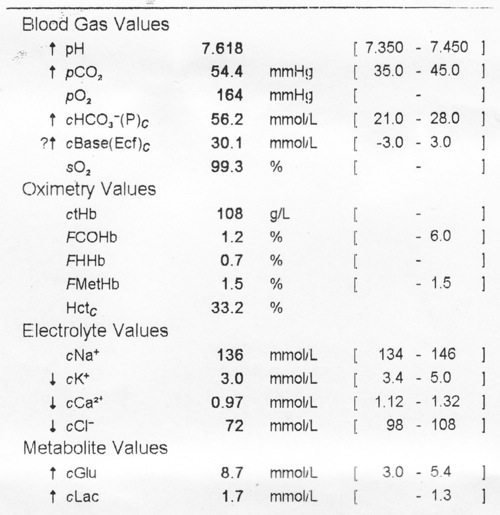

Blood gases will typically show a hypokalaemia, hypochloraemic metabolic alkalosis2 (Figure 1). This is due to the loss of hydrochloric acid with the repeated vomiting of stomach acid causing a hypochloraemia and metabolic alkalosis2. The kidneys will then exchange potassium to retain protons to attempt to compensate, leading to a hypokalaemia2. Metabolic derangement is less commonly seen now, due to earlier presentation and diagnosis3.

Figure 1: Blood gas demonstrating hypochloraemic, hypokalaemic metabolic alkalosis

Management

Peri-operatively it is important to correct any underlying metabolic abnormalities. Patients may require 10-20ml/kg fluid boluses for acute hypovolaemia. Oral feeding should be stopped and a NG tube passed and aspirated at 4 hourly intervals. Rehydration should then be commenced at 150ml/kg/day, using crystalloid as per trust policy. Blood gases and U+E’s should be checked regularly, and acted upon accordingly. Once dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities have been corrected, fluid can be reduced to usual maintenance rates.

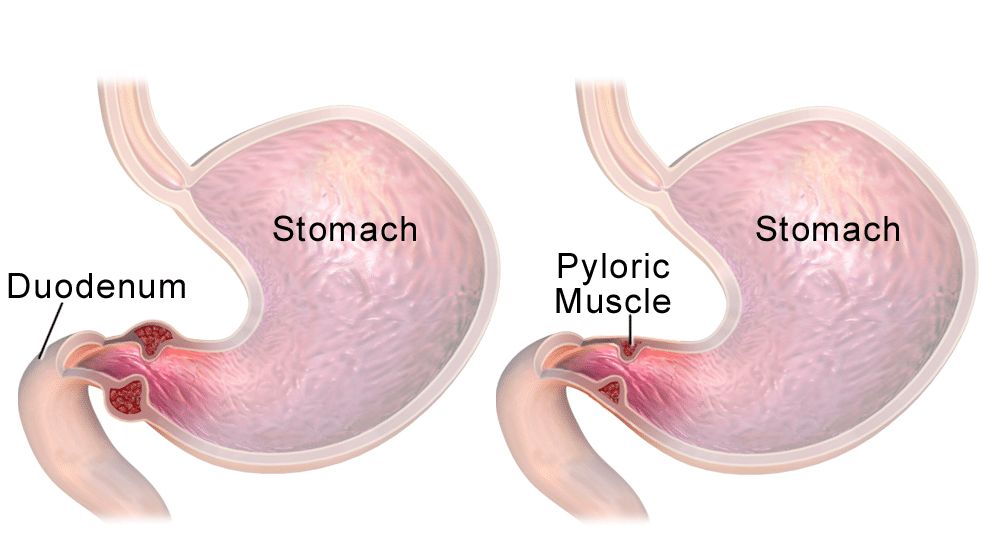

Pyloric stenosis is surgically managed, with a Ramstedt’s pyloromyotomy7 and should not be undertaken until any fluid or electrolyte abnormalities have been correction. Surgery can be performed laprascopically or through a supra-umbilical incision and the muscle is divided along down to the mucosa7 (Figure 2).This is successful in the majority of patients, with only 1-2% experiencing restenosis2. Babies can resume feeding after 6 hours, although there may be some residual vomiting8. Post–operative vomiting is common after surgery, due to gastric distension and dysmotility9, and is not necessarily a sign of incomplete myotomy.

Figure 2: Diagrammatic representation of pyloric muscle before and after surgical correction

Complications

Pre-operative:

- Hypovolaemia

- Apnoea – secondary to hypoventilation associated with metabolic acidosis

Post-operative:

- Wound dehiscence

- Infection

- Bleeding

- Perforation

- Incomplete myotomy

References

| 1 | Pandya, S. Heiss, K Pyloric Stenosis in pediatric surgery: an evidence-based review. Surgical Clinics of North America 2012;92:527-539 |

| 2 | Taylor, N. Cass, D. Holland, A. Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: Has anything changed? Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 2012;49:33-37 |

| 3 | Kamata, M. Cartabuke, R. Tobias, J Perioperative care of infants with pyloric stenosis. Pediatric Anesthesia 2015;25:1193-1206 |

| 4 | Godbole, P. et al Ultrasound compared with clinical examination in infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Archives of Disease in Childhood 1996;75:335-337 |

| 5 | Said, M et al Ultrasound Measurements in Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis: Don’t Let The Numbers Fool You. The Permanente Journal 2012;16:25-27 |

| 6 | Dawes, L Pyloric stenosis as seen on ultrasound is a 6 week old [Internet] ; [cited 29th March 2018] Available: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pyloric-stenosis.jpg |

| 7 | Sana, N. et al Laparoscopic vs open pyloromyotomy for infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: an early experience. Mymensingh Medical Journal 2012;21:430-434 |

| 8 | Great Ormond Street Hospital. Pyloric Stenosis [Internet] ; [cited 3rd March 2018] Available: http://www.gosh.nhs.uk/medical-information-0/search-medical-conditions/pyloric-stenosis |

| 9 | Irish, M. S. Pediatric Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis Surgery Treatment and Management [Internet] ; [cited 29th March 2018] Available: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/937263-treatment |