Introduction

Coronaviruses are a strain of viral pathogens that can affect humans. They include a wide spectrum of presentations from a mild flu like illness to respiratory failure and death. This article focusses on COVID-19 and its presentation and management in the paediatric population. It is important to stress that this information is evolving as our understanding of this condition improves. For the latest healthcare guidance you should consult the World Health Organizations information page on coronavirus.

Epidemiology

Since the discovery in the 1930’s, there have been a number of coronaviruses identified that affect animals and humans. A new coronavirus was identified in 2019 following a series of patients presenting with pneumonia in Wuhan, China. This led to a worldwide pandemic that, as of June 8th 2020, had over 7 million cases worldwide and 400,000 confirmed deaths (1). Johns Hopkins University produced a map to document the spread of infection which can be accessed here (2).

Whilst anyone can acquire COVID-19, it appears to mainly affect older patients and those with underlying medical health problems. Overall, most children present with mild symptoms or remain asymptomatic (3)(4).

Pathophysiology

The virus resulting in COVID-19 is ‘severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2’ or SARS-CoV-2 for short. Its main route of transmission is thought to be via respiratory droplets through coughing, sneezing and talking. This has led to various social distancing measures throughout the world to combat the spread amongst humans.

It is currently thought that the severity of COVID-19 may correlate to the body’s immune response. Those patients experiencing a more severe presentation show features of ‘cytokine storm syndromes’ where mortality could be due to ‘virally driven hyperinflammation’ (5).

Risk factors

Although COVID-19 can affect anyone, certain risk factors may result in increased severity of illness. In adults, these include increasing age and underlying health conditions such as diabetes mellitus, chronic lung disease, cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease (6). Certain conditions that would place children in the ‘extremely vulnerable’ category include:

– Solid organ transplant recipients

-Certain cancers/those undergoing treatment

-Severe respiratory conditions e.g. cystic fibrosis, severe asthma

-Immunodeficiency disorders e.g. SCID

-Those taking long term immunosuppressive therapies

There is insufficient evidence at present to determine the effects of coronavirus in-utero. One study of the placentas of 3 COVID-19 positive pregnant women found no pathological changes (7) with all 3 newborns subsequently testing negative for COVID-19. A systematic review including 51 pregnant women showed no evidence of vertical transmission of COVID-19 (8). Thus, at present, COVID-19 is not thought to adversely affect the foetus, at least in the third trimester.

Clinical features

History

The clinical features of COVID-19 from history may include (9)(10):

-Fever (56%)

-Dry cough (54%)

-Headache (28%)

-Sore throat (24%)

-Myalgia (23%)

-Shortness of breath (13%)

-Diarrhoea (13%)

-Nausea/vomiting (11%)

-Coryza (7.2%)

-Abdominal pain (5.8%)

One of the symptoms of fever, cough, or shortness of breath was found in 73% of children testing positive. This is less than the 93% of adults and suggests that children may be asymptomatic carriers of the infection. These features usually occur within 14 days of exposure, however the majority of cases become apparent after 5 days (11).

Examination

Examination of the child may reveal fever and increased work of breathing. This could include:

-Low oxygen saturations

-Increased respiratory rate

-Subcostal/intercostal recession

-Tracheal tug

-Tachycardia

-Crackles on auscultation of the chest

It is important to note that current RCPCH guidance advises that the oropharynx should only be examined if essential and that personal protective equipment should be worn if performed (12). This is based on evidence from ENT specialists that the upper airway may be a site of viral replication and potential transmission (13). The RCPCH state that if a diagnosis of tonsillitis is suspected based on history then the feverpain scoring system can be used to determine if antibiotics are indicated. This is validated in children from the age of 3 and is outlined on our tonsillitis page. The RCPCH suggest starting with a score of 2 in lieu of examination and considering antibiotics in those whose feverpain score is 4-5. If the score is 3 or less then safety netting advice is appropriate.

Paediatric Inflammatory Multisystem Syndrome (PIMS-TS)

Paediatric Inflammatory Multisystem Syndrome Temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection (PIMS-TS) is a new phenomenon that has been recognised during the COVID-19 pandemic (14). It can involve features of:

-Toxic shock syndrome

-Atypical Kawasaki disease

-Blood parameters consistent with severe COVID-19 (see below)

-Coronavirus positive OR negative

In this cohort of patients, abdominal pain and gastrointestinal symptoms were more common, as was cardiac inflammation. Given the limited information available at present, it is difficult to say whether this multi-system inflammatory disease could be attributable to COVID-19 or not and more evidence is needed.

Spectrum of severity

The severity of COVID-19 has been said to range from mild to critical involving the following criteria (15):

-Mild: No pneumonia or mild pneumonia

-Severe: Dyspnoea, oxygen sats <93%, >50% lung infiltrates within 24-48 hours

-Critical: Respiratory failure, septic shock, and/or multiple organ dysfunction/failure

Disease progression can be fast meaning that patients initially presenting with mild symptoms may go on to develop dyspnoea and more severe symptomatology. Most paediatric patients will experience a mild, potentially asymptomatic illness course.

Differential diagnosis

A large proportion of paediatric medicine can include non-specific respiratory symptoms, fever, or both. Thus, the differential diagnosis can be wide and may overlap but may include:

-Upper respiratory tract infection (tonsillitis, otitis media etc)

-Lower respiratory tract infection (pneumonia)

-Exacerbation of asthma

-Viral induced wheeze

-Allergy (consider anaphylaxis in sudden onset difficulty in breathing)

-Gastroenteritis

-Urinary tract infection (obtain urine dip)

-Sepsis

-Kawasaki Disease

-Diabetes Mellitus (If presenting with shortness of breath think of Kussmaul breathing and consider checking the blood glucose)

This list is not exhaustive and, as always, it is important to consider signs and symptoms on a case by case basis.

Investigations

The vast majority of paediatric patients will require no investigation and should follow country specific guidance on self-isolation and social distancing (see below).

Current practice is to swab suspected COVID-19 patients if they require admission to hospital such as for oxygen support. This includes a viral throat and nose swab. Further investigations will depend on the clinical picture but may include:

-Chest X-ray (Bilateral infiltrates on. Radiopaedia have a good selection of CXR’s and CT scans here)

-Inflammatory markers (CRP and ESR elevated)

-Full blood count (lymphonpenia, neutrophilia)

-Liver enzymes (elevated)

-Lactate dehydrogenase (elevated)

-D-dimer (raised)

-Nasopharyngeal swabs (note: the presence of other respiratory pathogens does not exclude COVID-19 as studies have demonstrated co-infection is possible (16))

In those with an isolated fever you may want to consider investigations to determine a source of the fever such as:

-Urine dip/MC+S

-Blood culture

-CSF culture/cell count

Management

Home care

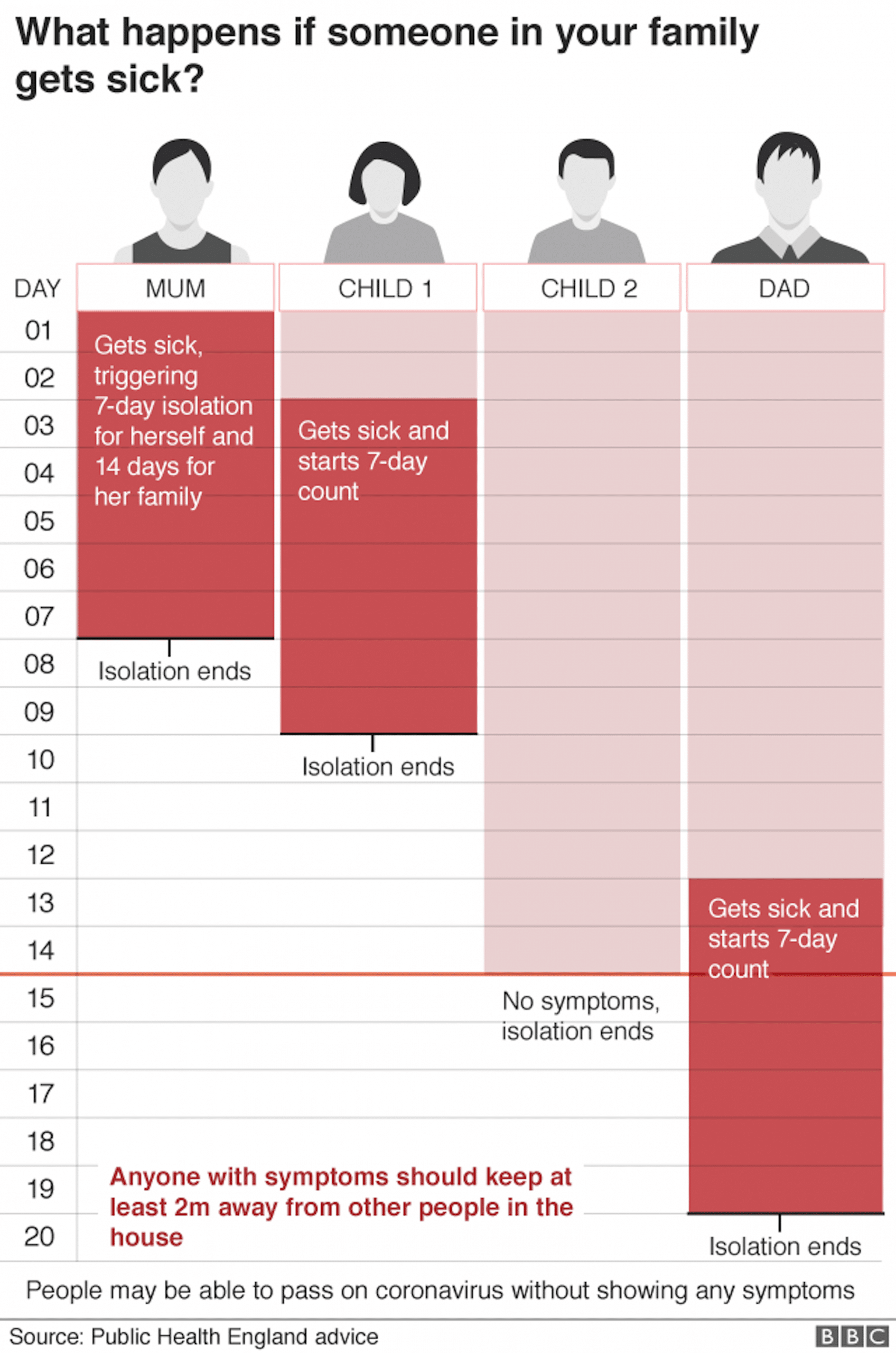

For most people, COVID-19 will be a mild illness requiring simple supportive treatment at home. In the United Kingdom, current guidance can be found here. It states that anyone presenting with symptoms of COVID-19 should isolate at home for 7 days from the onset of symptoms. Other members of the household are required to isolate for 14 days. The BBC have produced a helpful diagram based on Public Health England advice to demonstrate this (figure 1).

Figure 1: Self-isolation guidance as per Public Health England, image courtesy of BBC news

Adequate safety net advice should be given to ensure that symptoms suggestive of deterioration are recognised quickly, prompting re-evaluation of the child. These include:

-Increased work of breathing (for neonates this may also include grunting or decreased feeding)

-Ongoing fevers not controlled with antipyretics

-Signs of dehydration (reduced wet nappies)

-Increased lethargy

-Pale, blotchy, blue or grey skin

Further advice and information can be found on the NHS Coronavirus in children page here.

Hospital admission

If a child requires admission to hospital they should be isolated and managed as per local guidance based on Public Health England recommendations (17). This will usually involve cohorting patients into COVID-potential patients and non-COVID patients. Those requiring admission under the paediatric team will need to be isolated and managed in an area that is able to deal with their supportive requirements (e.g. ward based care vs Paediatric Intensive Care Unit).

The mainstay of treatment is supportive and may include:

-Oxygen supplementation with escalation of respiratory support as per local pathways (e.g low flow oxygen > high flow oxygen > CPAP > BiPAP >Mechanical ventilation)

-Observation of fluid management and instigation of parenteral fluids if required

-Continued use of regular medications unless contraindicated (including NSAIDs)

-Antibiotics may be used for complications (such as secondary bacterial pneumonia or suspected sepsis) but these will have no effect on COVID-19

-If other differentials are considered then treatment for these may also be indicated (e.g. IVIG and aspirin in Kawasaki’s Disease)

-Inotropic support

Some therapies are under investigation such as anti-viral or immune modulation treatments. These should only be considered in the context of treatment trials (e.g. the RECOVERY trial) and after liaison with a paediatric infectious disease unit (17).

Complications

The main severe complication of COVID-19 is Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), which can develop shortly after the onset of dyspnoea and require mechanical ventilation (18). PIMS-TS, sepsis, multiorgan failure, arrythmias and death have also been reported.

Prognosis

Our knowledge about COVID-19 is increasing daily but the long term implications may not be known for some time. What we do know is that death from COVID-19 appears to be extremely rare in paediatrics (4). However, more information is required on the systemic inflammatory response condition that has recently been documented.

References

| [1] | World Health Organization. Situation report 98, April 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200427-sitrep-98-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=90323472_4 |

| [2] | Johns Hopkins University, Coronavirus resource centre 2020. Accessed April 2020 at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html |

| [3] | Castagnoli R, Votto M, Licari A, Brambilla I, Bruno R, Perlini S, Rovida F, Baldanti F, Marseglia GL. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Infection in Children and Adolescents. A Systematic Review. JAMA Pediatr. 2020. |

| [4] | Ludvigsson, JF.Systematic review of COVID‐19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatr. 2020; 00: 1– 8. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15270 |

| [5] | Mehta, P., McAuley, D.F., Brown, M., Sanchez, E., Tattersall, R.S. and Manson, J.J., 2020. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression.The Lancet, 395(10229), pp.1033-1034. |

| [6] | Huang, C., Wang, Y., Li, X., Ren, L., Zhao, J., Hu, Y., Zhang, L., Fan, G., Xu, J., Gu, X. and Cheng, Z., 2020. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The Lancet, 395(10223), pp.497-506. |

| [7] | Chen S, Huang B, Luo DJ, et al. [Pregnant women with new coronavirus infection: a clinical characteristics and placental pathological analysis of three cases]. Zhonghua Bing li xue za zhi = Chinese Journal of Pathology. 2020 Mar;49(0):E005. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112151-20200225-00138. |

| [8] | Della Gatta, A.N., Rizzo, R., Pilu, G. and Simonazzi, G., 2020. COVID19 during pregnancy: a systematic review of reported cases. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. |

| [9] | World Health Organization. Coronavirus. Accessed at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_3 |

| [10] | Bialek, S., Gierke, R., Hughes, M., McNamara, L.A., Pilishvili, T. and Skoff, T., 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Children—United States, February 12–April 2, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(14), p.422. |

| [11] | Bai, Y., Yao, L., Wei, T., Tian, F., Jin, D.Y., Chen, L. and Wang, M., 2020. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. Jama, 323(14), pp.1406-1407. |

| [12] | RCPCH COVID-19 guidance for paediatric services. Accessed at: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/covid-19-guidance-paediatric-services |

| [13] | Lu D, Wang H, Yu R et al. Integrated infection control strategy to minimize nosocomial infection of corona virus disease 2019 among ENT healthcare workers. J Hosp Infect 2020 |

| [14] | COVID-19: Alert over multisystem hyperinflammatory state in children. Accessed from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/paediatric-inflammatory-multisystem-syndrome-and-sars-cov-2-rapid-risk-assessmenthttps://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/929415 |

| [15] | Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China:Summary of a Report of 72 314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020;323(13):1239–1242. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2648 |

| [16] | Xia, W., Shao, J., Guo, Y., Peng, X., Li, Z. and Hu, D., 2020. Clinical and CT features in pediatric patients with COVID‐19 infection: Different points from adults.Pediatric pulmonology, 55(5), pp.1169-1174. |

| [17] | RCPCH COVID-19 guidance for acute settings. Accessed at: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/covid-19-guidance-acute-settings |

| [18] | Wang, D., Hu, B., Hu, C., Zhu, F., Liu, X., Zhang, J., Wang, B., Xiang, H., Cheng, Z., Xiong, Y. and Zhao, Y., 2020. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China.Jama, 323(11), pp.1061-1069. |