Introduction

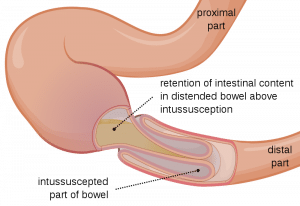

Intussusception is the movement or ‘telescoping’ of one part of the bowel into another. The proximal bowel segment is referred to as the intussuceptum whilst the distal segment as intussucipiens. (1)

Epidemiology

The peak incidence of intussusception is between 5-7 months of age (4) and rare to occur after 2 years (2). Boys are twice as more likely to be affected than girls (1,2).

Pathophysiology

The telescoping of one bowel segment into another can lead to intestinal obstruction (fig 1.). Although intussusception can occur anywhere along the gastrointestinal tract up to 90% of cases are of the ileo-colic type whereby the distal ileum passes into the caecum through ileo-caeceal valve (2,3).

Risk factors

Most cases are idiopathic but in approximately 25% of cases an underlying pathological cause can be identified. These pathological causes create a lead point in the intestinal wall enabling the bowel to telescope more easily. Research has shown there to be an association between recognised viruses such as rotavirus and the development of intussuception (4). Some pathological causes of intussusception include the following (2,5):

- Meckel diverticulum (most common)

- Polyps

- Henoch-Schönlein purpura

- Lymphoma and other tumors

- Post-operative

A pathological cause should be suspected if the child is older (5,3) or has a high recurrence rate (5).

Clinical features

History

The parent will report their child as having a sudden onset of inconsolable crying episodes. Pallor can be observed and in an attempt to alleviate pain the child may draw up their knees to their chest.

In-between episodes the parents will normally report the child returns to their normal self. With a delayed presentation the child can appear lethargic and anorexic.

In the later stages passed stools can appear to have a characteristic red-current consistency due to the presence of blood and mucus.

In older children, classical features of intestinal obstruction may be more pronounced such as:

- Vomiting

- Abdominal pain

Examination

The child should be examined promptly if a diagnosis is suspected

During examination of the abdomen the following should be assessed:

- Distention

- A palpable ‘sausage-shaped’ abdominal mass which can be found in the right upper quadrant (ileo-ceceal type)

- Signs of peritonism

- Presence of bowel sounds

The child should also be examined for signs of dehydration or shock to assess severity. Check out our fluid management article for more information.

Differential diagnosis

The differential for intussusception needs to be considered in relation to the child’s age and presenting features. It may include:

-

- Colic (excessive crying and drawing up of legs in otherwise well infant)

- Testicular torsion (always check testes in a male infant presenting with excessive crying)

- Appendicitis (tends to occur in older children. Pain might be localised to right iliac fossa)

- Gastroenteritis

- Volvulus

Diagnosis and investigations

Diagnosis is confirmed radiologically:

- AXR may confirm the diagnosis, however is not recommended due to low sensitivity (~50%) (1,3,6). It may show:

- Distended small bowel loops

- A curvilinear outline of the intussuception

- Absence of bowel gas in colon distal to intussuception site

- If perforation has occurred Rigler’s sign may be present (fig 2)

Figure 2: Rigler’s sign. The bowel appears to have a double wall, as gas (which has a lucent appearance) is trapped inside and outside of the bowel.

- Abdominal ultrasound: ultrasound is the preferred method of diagnosis (6) as it has a high sensitivity in comparison (98-100%) and can exclude alternative diagnoses (2,6). The following signs can be observed (2,6)

- Doughnut/target sign on a transverse plane, as can be seen on https://radiopaedia.org/articles/target-sign-intussusception?lang=gb

- Pseudokidney sign on a longitudinal plane

- Contrast enema: A GI contrast study can reveal a diagnosis of intussusception as the contrast media fails to adequately pass through the obstruction. In some cases it may also be therapeutic as the introduction of contrast media into the bowel may reverse the bowel invagination. This method is contraindicated if there is evidence of peritonitis or perforation.

Management

If there are any signs of shock or dehydration adequate fluid resuscitation should be given immediately. Nasogastric tube insertion may also help decompress the obstructed bowel. Subsequent management involves either nonoperative or surgical reduction. In approximately 5% of cases spontaneous reduction may also occur.

Nonoperative reduction

This involves the use of an air or contrast enema to reduce the intussuscepted bowel. This intervention is usually performed by the radiologist or paediatric surgeon at the time of diagnosis with USS. Evidence of peroration, peritonitis or uncorrected shock on examination are contraindications for this intervention (3,6). Liquid enemas can also be used but are considered less safe, take longer to perform and the outcomes are technique dependent (6). It should be noted that in those children in which a pathological lead point is suspected, therapeutic enema is less likely to be successful and may be contraindicated.

Surgical reduction

Should a child have any contraindications to enema use or enema intervention is unsuccessful, surgery is required to manually reduce the intussusception (3,6). This is usually straightforward but if there are any areas of necrotic bowel wall then resection of these areas is required. It is also prudent to try and identify any lead point in the bowel wall.

Complications

If left untreated three main complications can occur

Obstruction

Intussuception is one of most common causes of bowel obstruction and therefore an important surgical emergency in young children (5,6)

Perforation

As the intussuceptum moves further into the intusscipiens the bowel mesentery, and therefore the supplying blood vessels, become stretched and constricted. This leads to venous congestion and oedema within the bowel wall (2,3,8). If left untreated will cause bowel necrosis and perforation resulting in a septic child.

Bowel perforation is also an associated risk with air enema use (8).

Dehydration and shock

Fluid and bowel contents can collect within the intussusception which can rapidly lead to dehydration and hypovolemic shock (3).

Prognosis

With appropriate management recurrence rates within 24 hours are low (0.9-2.7%) (7). Mortality rates are <1% (5).

References

| 1. | Charles, T., Penninga, L., Reurings, J.C. and Berry, M.C.J., 2015. Intussusception in children: a clinical review. Acta chirurgica Belgica, 115(5), pp.327-333.

|

| 2. | Waseem, M. and Rosenberg, H.K., 2008. Intussusception. Pediatric emergency care, 24(11), pp.793-800.

|

| 3. | Illustrated Textbook of paediatrics fourth edition Tom Lissauer, Graham clayden

|

| 4. | Jiang, J., Jiang, B., Parashar, U., Nguyen, T., Bines, J. and Patel, M.M., 2013. Childhood intussusception: a literature review. PloS one, 8(7), p.e68482.

|

| 5. | Stringer, M.D., Pablot, S.M. and Brereton, R.J., 1992. Paediatric intussusception. British journal of surgery, 79(9), pp.867-876.

|

| 6. | Applegate, K.E., 2009. Intussusception in children: evidence-based diagnosis and treatment. Pediatric radiology, 39(2), pp.140-143.

|

| 7. | Gray, M.P., Li, S.H., Hoffmann, R.G. and Gorelick, M.H., 2014. Recurrence rates after intussusception enema reduction: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics, pp.peds-2013.

|

| 8. | Del-Pozo, G., Albillos, J.C., Tejedor, D., Calero, R., Rasero, M., de-la-Calle, U. and Lopez-Pacheco, U., 1999. Intussusception in children: current concepts in diagnosis and enema reduction. Radiographics, 19(2), pp.299-319.

|