This article is based on guidance from the Advanced Life Support Group guidelines for paediatric basic and advanced life support. The content is provided as an information resource only and is not to be used or relied on for any diagnostic or treatment purposes. Local or national up to date guidelines should be sought for the care of the patient.

Introduction

Possibly the most important skill of any Paediatricians career is the ability to assess for signs of life and perform basic life support. A simple algorithm can be followed in order to easily achieve this skill

Pathophysiology

The outcome of cardiac arrest in children is poor. In children, the most common cause of cardiorespiratory arrest is due to a respiratory problem causing prolonged hypoxaemia resulting in cardiac arrest. At the point of arrest the organs, including the brain, have experienced significant hypoxic damage; a primary cardiac cause is very rare.

Causes could include birth asphyxia, inhalation of foreign body, acute asthma or bronchiolitis. Respiratory arrest can also be secondary to neurological dysfunction or ingestion of drugs such as opiates.

Risk Factors

Children at risk include those at risk of aspiration such as those with:

- decreased GCS

- an underlying cardiac condition

- anaphylaxis

- drug ingestion

- neuromuscular disorders

- respiratory pathology

- foreign body

- post cardiac surgery

- drowning

- trauma

- medication that causes a reduction in GCS

- any anatomical abnormality with the ability to obstruct the airway

- non accidental injury (see our child protection article for more information)

Clinical Features from history and examination

The cause of the arrest does not change the initial approach to a collapsed child. However, if there is a witnessed collapse of a child, an underlying cardiac condition becomes more likely and it is important this is relayed to the team providing Advanced Life Support.

Differential Diagnoses

- Choking

- Opiate ingestion

- Overdose of toxic substance

- Decreased level of consciousness due to neurological disorder/ head injury

- Hypoglycaemia

Management

Algorithm

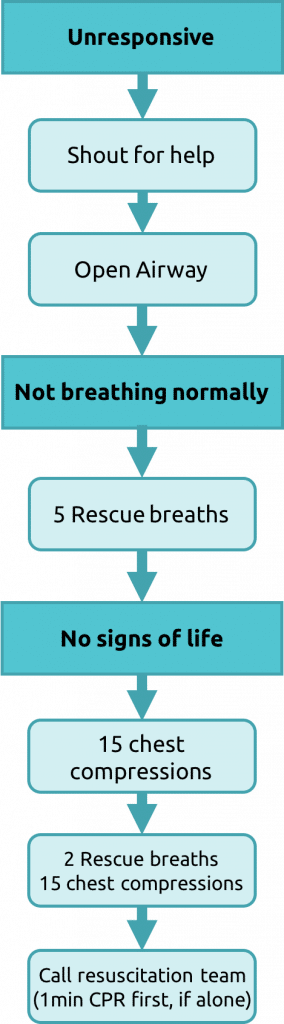

BLS can be confidently performed by following a structured algorithm (figure 1). This allows it to be used in countries all over the world and by varying allied health care professionals as long as the algorithm is known.

(1) Advanced Life Support Algorithim as per APLS (picture adapted)

Initial approach

‘The 3 S’s’- SAFETY, STIMULATE, SHOUT:

Check for Safety– is it safe to approach?

In an out of hospital environment it is particularly important that the rescuer does not himself become a second victim.

Stimulate– asking the child ‘are you ok, can you hear me?’ and gently applying stimulation in the form of shaking an arm or gentle stimulation by rubbing the chest.

Shout– shout for help- to other passersby!

Airway opening manoeuvres:

The child may have stopped breathing due to an obstructed airway caused by a foreign body or the tongue may have fallen back obstructing the pharynx. An attempt to open the airway can be done by using the head tilt and chin lift manoeuvre (see approach to the seriously unwell child).

In infants (<1 year) the aim is for a neutral position due to relatively short fat necks. In older children a ‘sniffing the morning air’ position is desirable. This can be achieved by placing one hand on the child’s head with the other under the child’s chin- apply pressure to tilt the head back gently. Injuries can be caused to the soft tissue so ensure you use the bony mandible.

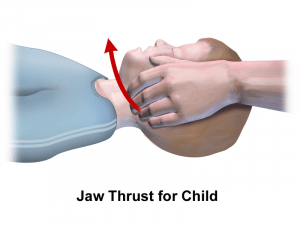

If there is a suspected neck injury the head tilt chin lift should be avoided and a jaw thrust implemented (figure 2). This can be done by using two or three fingers on each side under the angle of the jaw and push up on both sides- to raise jaw. If all of the measures above fail to open the airway- even in the event of a C-spine injury maintaining the airway would be the priority.

(2) Jaw thrust

Then you can assess the patency of the airway by ‘LOOKING, LISTENING AND FEELING’

Look: for any obvious obstruction- blood, vomit, trauma and look for any signs of abdominal or chest wall movement

Listen: for breath sounds

Feel: for breath on your cheek

This sequence of ‘Look, listen and feel’ should take a total of 10 seconds.

If once the airway has been opened normal breathing ensues the rescuer then turns the child onto their side (into the recovery position) and maintains their airway until further help arrives. If the airway opening manoeuvres do not result in spontaneous breathing then rescue breaths must be given.

Breathing

5 x initial rescue breaths must be given

The airway must be kept open during the rescue breaths. If the rescuer is out of hospital without any equipment then mouth to mouth can be used to give the breaths. In older children this requires the nose to be pinched closed. In infants the rescuer should attempt to cover both the nose and mouth with their mouth.

The breaths given should be able to make the child/ infants chest rise as normal. Slow exhalation is required (around 1-1.5 seconds) – too vigorous can cause the stomach to inflate and contents to be regurgitated.

A breath should be taken in between by the rescuer to increase the oxygen concentration, ensuring you move your mouth away from the patients so as not to breathe in their exhaled air.

If the chest does not rise- it implies the airway is not clear. Try to re-position the airway– if there are two rescuers this can be done by a 2 person jaw thrust– one maintaining the airway whilst the other provides the breaths.

If this occurs in hospital a bag and mask device can be used to provide the rescue breaths rather than a mouth.

Circulation

Once the rescue breaths have been given attention should be turned to the circulation and rapid assessment to see if there is a pulse present. If there are no ‘signs of life’ i.e. spontaneous breathing or movement after the rescue breaths AND there is no central pulse present after 10 seconds of palpation, or heart rate <60 then cardiac compressions should be the next step.

In children the carotid, brachial or femoral artery can be palpated. In infants whom have a short neck- it is difficult to palpate the carotid artery- the brachial artery should be used (medial aspect of antecubital fossa).

Chest compressions

Chest compressions should be commenced if

- NO SIGNS OF LIFE

- NO PULSE

- HR <60

Chest compressions should cause a compression of the lower half of the sternum by around 1/3 of its depth. It is important that the chest fully recoils prior to the next compression.

For infants, the most effective position with two BLS providers present is the hand encircling technique (figure 3). The rescuers hands are placed around the lower half of the infants sternum and compressions are carried out with the thumbs. If only one provider two finger technique should be used with the other hand stabilising the infants head (figure 4).

(3) Example of encircling technique

(4) Example of a 2 finger technique

For children, the rescuer should use the heel of their hand over the lower half of the sternum. The arm should remain straight and chest should be compressed to 1/3 of the depth. For larger children or small rescuers two hands can be used one on top of the other with fingers interlocked to perform the compressions.

Ratio: 15 compressions to 2 ventilations. Compression rate 100-120 per minute. If it is a single rescuer and no help has arrived emergency services should be contacted 1 minute after commencing compressions.

BLS should not be interrupted (other than a phone call from the rescuer for help) unless the child moves or takes a breath (shows ‘signs of life’). A young child could be carried with BLS ongoing whilst the rescuer goes for help.

Definitive and Long-term management

Transfer to hospital is needed if in the external environment or if in a hospital setting progression to Advanced Life support with the help of a full Paediatric Resuscitation Team.

This would include Accident and Emergency Nurses and Doctors (if in the A and E department), Paediatric Doctors and Nurses, Anaesthetic teams, Intensive care Doctors and Nurses, porters and somebody allocated to talk to parents.

If this occurs in a hospital without rapid access to Paediatric Intensive Care timely discussions with the local Paediatric transfer service e.g. KIDS in West Midlands, is crucial in finding a hospital with the required facilities.

Complications including prognosis

The outcome of cardiopulmonary arrest in children is poor. Of those whom survive many are left with untreatable neurological deficits. As with the adult population the worst outcome is in those whom have an out of hospital arrest- especially if CPR has been ongoing for longer than 20 minutes.

Further resources

This video outlines the Basic Life Support algorithm

Video 1: Basic Life Support on a child (video courtesy of University of Leicester)

References

| (1) | Picture adapted: https://www.resus.org.uk/resuscitation-guidelines/paediatric-basic-life-support/ |

| (2) | Advanced Life Support Group. Advanced paediatric life support—the practical approach, 5th London: Wiley- Blackwell 2014 |

| (3) | The rest of the article is based on information from the APLS manual- reference: Advanced Life Support Group. Advanced paediatric life support—the practical approach, 5th London: Wiley- Blackwell 2014 |

Authors:

First draft: Dr Vicki Currie

Senior Review: Dr Helen Stewart (Paediatric specialist registrar)