Cerebral palsy is a group of lifelong conditions that affect coordination and movement.

It can be associated with cognitive impairment, epilepsy, visual impairment and difficulties with feeding and communication. Cerebral palsy is a non-progressive disorder, meaning the initial damage does not worsen. However, the presentation of symptoms and their effect on an individual’s functioning and participation can change.

Epidemiology

Cerebral palsy occurs in approximately 2-3.5 per 1000 children in developed countries. It is often not identified at birth as symptoms become more apparent as the child develops and demonstrate delayed developmental milestones.

Some studies report that the prevalence is higher in less developed countries due to differences in health care provision and maternal health. It is recognised that rates are higher in preterm births and multiple births.

Pathophysiology

Cerebral palsy is caused by an acquired injury to the developing brain and can occur prenatally, perinatally or postnatally by mechanisms such as brain malformations, hypoxic damage, infection and intraventricular haemorrhage.

Maria is a 34-year-old first-time mother to be. She attends her antenatal appointment at 28 weeks gestation with her midwife as part of her routine care. Maria is worried as a friend’s child has recently been diagnosed with cerebral palsy at the age of 14 months. She wants to know if her baby will have it?

What risk factors do you know of for cerebral palsy?

Risk Factors

Risk factors can be divided into when they are encountered in the prenatal, perinatal and postnatal periods. Some examples include:

Prenatal

- Multiple gestations

- Maternal infections e.g. chorioamnionitis, urinary tract infection

- Maternal TORCH illnesses (toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex) which may not present significant disease in the mother

- Certain maternal medications (teratogens) e.g. warfarin, sodium valproate

- Placental abruption

- Foetal malformations

Perinatal

- Preterm birth

- Asphyxia at birth e.g. hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy

- Neonatal sepsis

- Intraventricular haemorrhage

Postnatal

- Traumatic head injuries including non-accidental injuries

- Meningitis/encephalitis

Maria gives birth to a little boy called Caleb at 38 weeks gestation. Following a difficult delivery, he spent almost two weeks in the special care baby unit and was discharged home. Maria speaks to his health visitor when he is 8 months old as she is concerned. Caleb is unable to sit independently and Maria feels his left leg does not move like his right. The health visitor makes a referral to paediatrics.

As the paediatrician, what information do you want to know from the history?

Clinical Features

From the History

- Maternal history e.g. illnesses and medications, family history of neurological disorders

- Antenatal history e.g. ultrasounds, obstetric visits, gestational diabetes

- Birth history e.g. gestation, delivery type, time spent in special care, Apgar score, sepsis

- Child’s developmental history e.g. parental description, health visitor reports

Often those felt to be at risk (especially if they were born preterm or had complications post-delivery) are followed up by the neonatology team up until the age of 2.

On Examination

The clinical presentation of cerebral palsy depends on the location and severity of the injury and the age of the child at presentation. Although the brain injury does not change with time, the signs and symptoms that a child displays might.

Delayed motor milestones or having a hand preference before the age of 1 are often the first signs. Physical examination may reveal reduced or increased muscle tone.

Caleb is now 6-years-old and has a diagnosis of cerebral palsy. He is a happy little boy who attends a mainstream school. Caleb uses a walker to get around home and school, and uses a wheelchair for school trips and days out with his family. He sees his Community Paediatrician regularly and has input from physiotherapy and occupational therapy. Both his legs are stiff and sometimes cause him pain.

How would you describe his cerebral palsy to other healthcare professionals?

Classification

Cerebral palsy (CP) can be described according to the type (e.g. spastic, dyskinetic, ataxic or mixed) or which parts of the body are affected (e.g. quadriplegia, diplegia) but the latter is used less often.

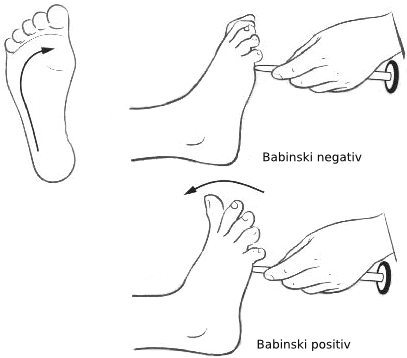

- Spastic CP occurs when cortex or pyramidal tracts are involved. It is the most common type and affects approximately 80% of children with cerebral palsy. Patients may have spasticity of the muscles, hyperreflexia, clonus and a positive Babinski reflex.

- Dyskinetic CP occurs when extrapyramidal tracts are involved and affects 10-15% of patients. Patients may have problems controlling movements of their hands, arms, feet and legs. Muscles of the face and tongue can also be affected making it difficult to swallow or talk.

- Ataxic CP occurs when the cerebellum is affected. These patients have problems with balance and coordination. They may also have problem with quick movements and movements that need a lot of control.

- Patients with mixed cerebral palsy may display features of each of these types.

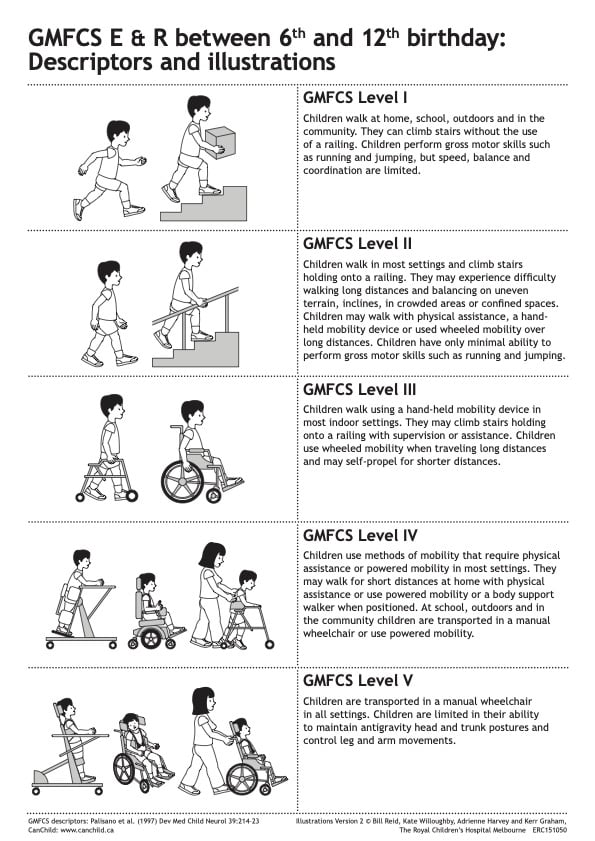

One of the most commonly used classifications is the GMFCS (Gross Motor Function Classification System), which is used to describe how cerebral palsy affects the child.

Differential Diagnosis

Differentials diagnoses should be considered in the absence of risk factors, unexpected neurological signs, family history of neurological disorders or where developmental skills have been acquired and then lost.

Conditions to consider include:

- Brain tumours

- Muscular dystrophy (e.g. Duchenne’s or Becker’s)

- Dystonia

- Spinal muscular atrophy

Investigations

Cerebral palsy is a clinical diagnosis based on history and examination. Additional investigations can be carried out if the diagnosis is in question and differentials need to be ruled out, or for understanding causation e.g. MRI indicating an area of damage.

Identification of cause may be important in cases where compensation is due to complications at birth where trauma could have been avoided.

Investigations such as cerebrospinal fluid sampling or muscle biopsies may be required if certain differentials need to be ruled out.

Management

Management options will not be the same for every person with cerebral palsy and should be discussed on a case-by-case basis and symptoms revisited at each appointment.

Medication

Medication can be used to lessen muscle stiffness, improve functional abilities, manage pain or prevent complications.

Botulinum toxin (botox) injections can be used to treat tightening of a specific muscle. The therapeutic effects may last 3-6 months. Oral muscle relaxants such as baclofen are often used to relax muscles.

Nutrition

Some people with cerebral palsy have difficulty chewing and/or swallowing foods. They may require a specialist diet or adjuncts to allow them to meet their nutritional requirements e.g. nasogastric feeding tube or PEG (percutaneous endoscopic gastronomy) feeding.

Therapies

A variety of therapies play an important role in managing cerebral palsy:

- Physiotherapy

- Occupational therapy

- Speech and language therapy

- Dietetics

- Bladder and Bowl/Incontinence team

Surgical procedures

Surgery may be needed to lessen muscle tightness or correct bone abnormalities caused by spasticity.

Selective dorsal rhizotomy (SDR) is offered in 5 centres in the UK and aims to reduce spasticity in children with cerebral palsy provided they meet specific criteria.

Associations and Complications

Complications in cerebral palsy are associated with the individual’s presentation and can vary throughout an individual’s life.

More common associations than when compared to the non-cerebral palsy population include:

- Chronic pain and contractures

- Urinary incontinence or retention and/or faecal incontinence or constipation

- Pressure injuries

- Epilepsy

- Mental health conditions e.g. anxiety and depression

- Susceptibility to infection e.g. pneumonia

- Malnutrition

References

- NICE CKS – Cerebral Palsy (last updated 2019); Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/cerebralpalsy

- Scope – Disability and Equality Charity Available at: https:///www.scope.org.uk

- Hoda, A.-H. & Zeldin, A., Medscape. Cerebral Palsy. [Online]; Available at: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1179555-overview

- Mayo Clinic, n.d., Cerebral palsy Mayo clinic. [Online]; Available at: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/cerebral-palsy/symptoms-causes/syc-20353999

- Eyvazzadeh, A., Healthline. What Causes Cerebral Palsy?. [Online]; Available at: https://www.healthline.com/health/what-causes-cerebral-palsy

- Marret, S. & Vanhulle, C. & Laquerriere, A., ScienceDirect. Chapter 16 – Pathophysiology of cerebral palsy. [Online]; Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780444528919000166#!