Introduction

Anaphylaxis is a severe, life-threatening, generalised or systemic hypersensitivity reaction involving the airway, breathing, and circulation.1 It is a clinical emergency that all health care professionals need to be able to recognise and manage.1

Epidemiology

In England, it is estimated that 1 in 1333 of the population has experienced anaphylaxis during their lifetime.1 Studies show that admissions with anaphylaxis increasing over the past two decades. Anaphylaxis is treatable when recognised and acted upon quickly. There are approximately 20 deaths per year due to anaphylaxis in the UK.1

Pathophysiology

Anaphylaxis is a type 1 hypersensitivity reaction.3

Hypersensitivity reaction – an overreaction of the immune system to an antigen which would not usually trigger an immune response.3

As for many immune reactions, a hypersensitivity reaction requires two different interactions of the immune system with the antigen,3 i.e., the patient will react to their second exposure to the allergen.

1st exposure to allergen: Th2 cells are primed, and the release of IL-4 causes B cells to switch their production of IgM to IgE antibodies. IgE antibodies bind to mast cells and basophils. The cells are now sensitised to the allergen.3

2nd exposure to allergen: Cross linkage of the antigen-specific IgE antibody bound to the sensitised cells causing mast cell degranulation and release of various mediators (leukotrienes, histamine and prostaglandins). This causes widespread vasodilation, bronchoconstriction and increased permeability of vascular endothelium.3

Hypersensitivity reactions can be divided into four types, by the most commonly known Gell and Coombs classification system,4 published in 1963 and still used today:

| Type 1 | Type 2 | Type 3 | Type 4 | |

| Definition | Immediate | Cytotoxic | Immune complex | Cellular/delayed |

| Timing of reaction | Minutes | Variable | Weeks | Days |

| Immune reactant | IgE | IgG | IgG | T effector cells |

| Example | Anaphylaxis | Acute transfusion reaction | Rheumatoid arthritis, vasculitis, glomerulonephritis | Contact dermatitis |

Table 1: Gell and Coombs classification of hypersensitivity reactions. Adapted from teachmephysiology.com3

Aetiology

Food triggers are common in children.1 Other causes include:

- Drugs: antibiotics, NSAIDs, neuromuscular blocking agents5,6,18

- Injections: radiocontrast dyes6

- Venom (Stings and bites): bees, wasps6

- Food: shellfish, nuts, peanuts, eggs, strawberries, wheat5,6

- Exercise-induced anaphylaxis: rare7

- Idiopathic: no identifiable stimulus, diagnosis of exclusion.1

Risk factors

Some groups may be at higher risk:

- Those with existing comorbidities (e.g. asthma, mast cell disorders, cardiovascular disease)1,18

- Those more likely to be exposed to the same allergen again (e.g. food triggers which are common in children)1

Cofactors

Cofactors increase the risk of allergic reactions happening or their severity. These include exercise, fever, acute infection, premenstrual status and emotional stress.2

Clinical features

Diagnosis of anaphylaxis is clinical. Allergy testing through referral to an allergy specialist helps prevent recurrence.8

History

- Take a careful history. Aim to determine the time between exposure to the potential allergen and the onset of symptoms.6

- A history of an acute onset of symptoms is a key diagnostic feature of anaphylaxis.8

Examination

It’s helpful to think about the signs and symptoms as you would using the A-E approach:

- Airway: lip, tongue, pharynx and epiglottis swelling, possibly causing cough, swallowing difficulty, hoarse voice and stridor5,8

- Breathing: tachypnoea, wheezing, cough, chest tightness, dyspnoea, hypoxia, hypercapnia, acute airway obstruction with laryngeal oedema and bronchospasm1,5,6

- Circulation/cardiovascular: dizziness, pallor, tachycardia, clammy skin, drowsiness, collapse, hypotension, prolonged CRT and shock.1,5,6,9,10 Arrhythmias and ECG changes may be present.5

- These circulatory changes occur due to peripheral vasodilation and increased permeability, causing plasma leakage from circulation and decreased intravascular volume.5

- Disability/Other:

- Neuro: confusion, anxiety, collapse, loss of consciousness9

- GI: abdominal cramping, D&V5,6

- Other: the feeling of impending death5

- Exposure: skin changes including urticaria, angioedema, pruritus and erythema1,5,6

Differential diagnosis

There are many differentials for anaphylaxis. As below differentials for anaphylaxis can be separated into life-threatening and non-life-threatening:

| Life-threatening | Differentiating features |

| Life-threatening asthma2 | Respiratory features, unlikely to involve skin, CVS and GIT |

| Septic shock (normal or low blood pressure with petechial or purpuric rash)2 | Core temp <36 or >38; however, do not use temperature as a predictor of sepsis!11 It is usually normal in anaphylaxis |

| Hereditary angioedema5 | Not usually accompanied by urticaria5 |

| Non-life threatening/less concerning | Differentiating features |

| Vasovagal episode2 | Absence of urticarial rash, angioedema, hoarseness, wheezing12Bradycardia as opposed to tachycardia in anaphylaxis12Abrupt onset of pallor as opposed to erythema in anaphylaxis12Will usually improve on lying down12 |

| Panic attack2 | Absence of hypotension, pallor, wheeze, urticarial rash2 |

| Breath-holding episode2 | Usually passes and resolves in less than 1 minute13 |

| Idiopathic (non-allergic) urticaria or angioedema2 | Skin changes only unlikely to be anaphylaxis |

Figure 1- Differential diagnoses of anaphylaxis. Adapted from the EAACI guideline.

Management

There are limited investigations that are of use in the Emergency Department if anaphylaxis is suspected. Using an A-E management approach and treating promptly as you go along is the key thing to remember. Investigations can come later! For this reason, we present the management of anaphylaxis before the investigations.

Prompt treatment with adrenaline and securing the airway are crucial to preventing life-threatening problems.8

Initial approach/management

As in all Paediatric emergencies, initial management should use the A-E approach, looking for signs and symptoms as described above.

Immediate Management

Throughout treatment, monitor (get from ALS) O2 saturations, blood pressure, and ECG.2

For dosages in children and how this differs in adults, please refer to the Anaphylaxis algorithms diagram above (figures 1 and 2)

- Diagnosis as above

- Call for help

- Remove suspected factors if still present (e.g. discontinue drug if suspected drug reaction).5 Depending on your location, lie the patient flat and raise their legs. A sitting position may be more comfortable in some cases, e.g. Breathing difficulty or pregnancy.2

- IM adrenaline 1:1000 – administer without delay into the anterolateral thigh2,5,14

- This can be repeated every 5 minutes if there is no improvement2,14

- Adrenaline has effects as both an a and a b agonist:

- a-adrenergic action: increases blood pressure15

- b- agonist-adrenergic effect: increases cardiac contractility and heart rate, dilation of bronchioles15

- Establish and maintain the airway. If upper airway oedema is present, get senior help immediately.2,5 100% high flow O2.2,5 Apply monitoring.

- If there is no response – repeat IM adrenaline after 5 minutes, IV fluid bolus.

- If there is no response after two doses of adrenaline, confirm help has been called.

Figure 4- A picture showing the injection site for IM adrenaline (EpiPen).

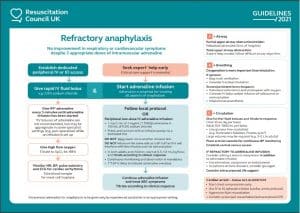

Refractory Anaphylaxis Algorithm

- Give IM adrenaline every 5 minutes until adrenaline infusion started

- Airway; Upper airway obstruction/stridor- nebulised adrenaline, senior airway support

- Breathing; Respiratory support via bag/mask or ventilation. Bronchospasm- nebulised salbutamol/ipratropium, IV salbutamol/aminophylline if required

- Circulation; Further fluid boluses if needed and monitor response; if refractory to adrenaline infusion, consider the second vasopressor, glucagon and consider ECMO

CARDIAC ARREST – follow ALS/PLS ALGORITHM

Picture 1: Anterolateral thigh, injection site for adrenaline

Investigations and Further Management

Mast cell tryptase

Mast cell tryptase is an enzyme produced almost exclusively by mast cells in IgE-mediated anaphylaxis (and in some haematological disorders).17 It is worth noting that although mast cell tryptase is widely used to support the diagnosis, it is not consistently elevated in children when food is the allergen or the main severe feature is respiratory.1

Timings of samples:

- Take a blood sample for mast cell tryptase testing immediately after starting treatment.5

- Take a second sample within 1-2 hours (no later than 4 hours) from the onset of symptoms.5

- In practice, a third sample is sometimes taken at the time of specialist follow-up in an allergy clinic – however, there is no guidance available for this online.

Further Management

Admission

- Children under 16 who have had emergency treatment for suspected anaphylaxis should be admitted under paediatrics, as biphasic responses may occur.1,5

- Biphasic anaphylaxis – after complete recovery of anaphylaxis, a recurrence of symptoms within 72 hours with no further exposure to the allergen. Manage in the same way as anaphylaxis.1

- Offer the patient and carer an appropriate adrenaline autoinjector (EpiPen) as an interim measure before the specialist allergy referral.1

Documentation

Make sure to document:

- All acute clinical features of the suspected anaphylactic reaction1

- Time of onset of the reaction1

- Circumstances immediately before the onset of symptoms1

- The trigger, if known1

Referral

- Offer referral to a specialist allergy service1

- Offer an appropriate adrenaline injector (EpiPen) in the period until the specialist allergy referral appointment, and advise them to carry it with them at all times.1

Information for the patient and their family

Before discharge, a professional with the appropriate skills and competencies should discuss with the patient and their carers:

- Signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis1

- Information about the risk of a biphasic reaction1

- What to do if an anaphylactic reaction occurs (i.e. use the adrenaline injector (including demonstration) and call emergency services)1

- Advice about avoiding suspected trigger1

- Information about specialist allergy service referral and patient support groups1

- Consider the use of individualised allergy action plans, e.g. BSACI allergy action plans

Complications

Anaphylactic shock (failure to deliver adequate oxygen to the tissues)6 is a life-threatening complication of anaphylaxis. This can cause respiratory and cardiovascular problems:

- Respiratory: airway narrowing of upper and lower airway6

- Cardiovascular: shock vasodilation, increased vascular permeability6

Prognosis

With prompt treatment, the overall prognosis of anaphylaxis is good. The risk of death increases in those with pre-existing asthma (particularly if poorly controlled) or in those asthmatics who fail to use or delay administering adrenaline.2

References

| No. | Reference |

| 1 | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Anaphylaxis: assessment and referral after emergency treatment. CG134. 2011 [updated 24 August 2020, Accessed 5 March 2021]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg134.

|

| 2 | Resuscitation Council (UK). Emergency treatment of anaphylactic reactions: guidelines for healthcare providers. 2012.

|

| 3 | TeachMePhysiology. Hypersensitivity Reactions [updated 2020, Accessed 5 March 2021]. Available from: https://teachmephysiology.com/immune-system/immune-responses/hypersensitivity-reactions/.

|

| 4 | Gell PGH, Coombs RRA. Clinical aspects of immunology. Philadelphia: Davis; 1963.

|

| 5 | Jonathan P. Wyatt RGT, Kerstin de Wit, Emily J. Hotton. Oxford Handbook of Emergency Medicine. Fifth edition, ed2020.

|

| 6 | Robert C. Tasker RJM, Carlo L. Acerini. Oxford Handbook of Paediatrics. Second edition, ed2013.

|

| 7 | Peter N Huynh M. Exercise-Induced Anaphylaxis. Medscape. 2017.

|

| 8 | BMJ Best Practice. Anaphylaxis. BMJ Best Practice, . 2020.

|

| 9 | NHS. Anaphylaxis [updated 29 November 2019, Accessed 10 March 2021]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/anaphylaxis/.

|

| 10 | Geeky Medics. Anaphylaxis Acute Management – ABCDE 2020 [Accessed 10 March 2021]. Available from: https://geekymedics.com/anaphylaxis/#:~:text=hypotension%20is%20severe.-,Clinical%20examination,and%20prolonged%20capillary%20refill%20time.

|

| 11 | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Sepsis: recognition, diagnosis and early management, NICE guideline [NG51] 2016 [updated 13 September 2017Accessed 10 March 2021].

|

| 12 | Cingi C, Bayar Muluk N. Differential Diagnosis for Anaphylaxis. Quick Guide to Anaphylaxis. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 221-35.

|

| 13 | NHS. Breath-holding in babies and children [updated 26 November 2019, Accessed 10 March 2021].

|

| 14 | BNFc National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Adrenaline/Epinephrine [Accessed 10 March 2021].

|

| 15 | Upchurch J. Receptors and the autonomic nervous system 2020 [Accessed 10 March 2021].

|

| 16 | S Shahzad Mustafa M. Anaphylaxis Treatment & Management. Medscape. 2018. |

| 17 | Waterfield T, Dyer E, Wilson K, Boyle RJ. How to interpret mast cell tests. Archives of disease in childhood – Education &amp; practice edition. 2016;1015:246.

|

| 18 | Murano A et al. European Academy of Allergy, Clinical Immunology (EAACI) Food Allergy, Anaphylaxis Guidelines Group. Anaphylaxis (2021 update). Allergy Aug 3 2021

|