Introduction

Appendicitis refers to inflammation of the appendix and is a common acute surgical presentation

It most commonly affects those aged between 10-30yrs old, however it can affect any age, and has an overall lifetime risk of 7-8%. It is one of the most common causes of abdominal pain, especially in younger patients.

Around 50,000 appendicectomies are performed per year in the UK. In this article, we shall look at the clinical features, investigations and management of acute appendicitis.

Pathophysiology

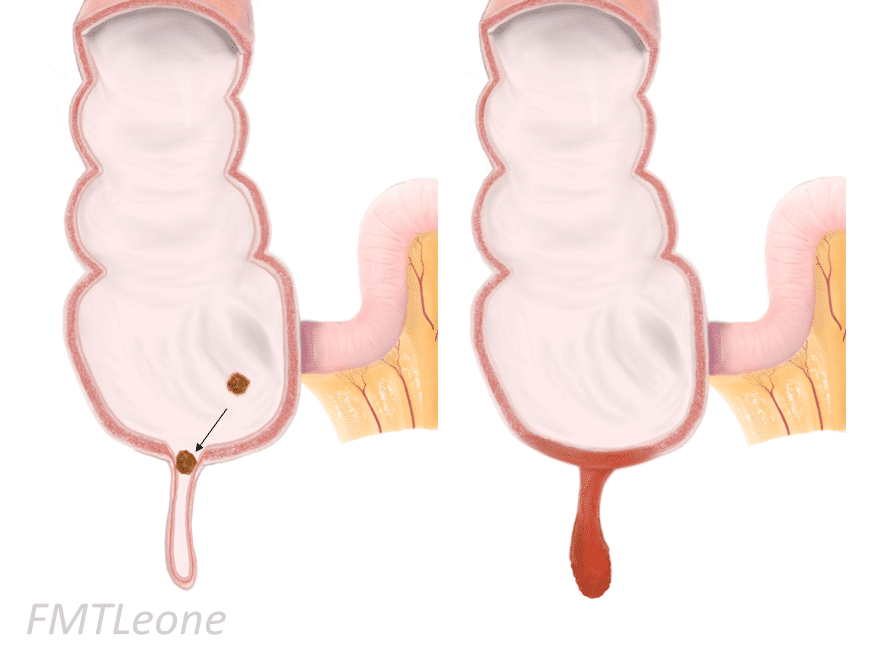

Acute appendicitis is typically caused by direct luminal obstruction, usually either secondary to a faecolith (Fig. 1) or lymphoid hyperplasia, or less commonly by a malignancy (such as a caecal adenocarcinoma or appendiceal neuroendocrine tumour)

When obstructed, commensal bacteria in the appendix can multiply, resulting in acute inflammation. Reduced venous drainage and localised inflammation can result in increased pressure within the appendix, in turn resulting in ischaemia within the appendiceal wall.

If left untreated, ischaemia can result in necrosis, which in turn can cause the appendix to perforate.

Risk Factors

- Family history – Twin studies suggest that genetics account for 30% of risk*

- Ethnicity – More common in Caucasians

- Environmental – Seasonal presentation during the summer

*No specific gene has been identified specifically, but the risk is roughly three times higher in members of families with a positive history

Clinical Features

The main symptom of appendicitis is abdominal pain. Classically, this will present with a dull peri-umbilical pain that is poorly localised (from visceral peritoneum inflammation), but later migrates to the right iliac fossa, becoming localised and sharp (from parietal peritoneum inflammation).

However, patients can present in a variety of ways, especially in children. Other associated symptoms include vomiting (typically after the pain, not preceding it), anorexia, nausea, or diarrhoea.

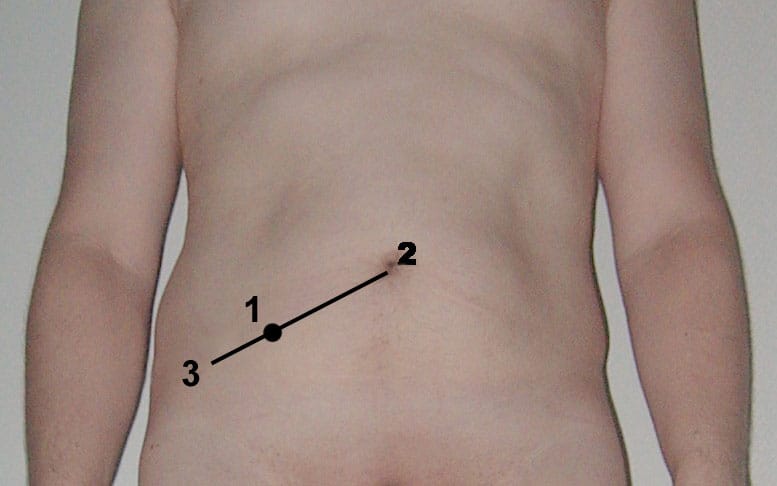

On examination, patients may demonstrate rebound tenderness and percussion tenderness over McBurney’s point (Fig. 2). This can progress to guarding, especially if the appendix is perforated. In severe cases, patients can show features of sepsis, including tachycardia, hypotension, and pyrexia.

In cases of an appendiceal mass (see below), a mass in the right lower abdomen may be palpable.

Specific signs that may be found on examination include:

- Rovsing’s sign – right iliac fossa pain on palpation of the left iliac fossa

- Psoas sign – right iliac fossa pain with extension of the right hip, suggestive of a retrocaecal appendix abutting the psoas muscle

Figure 2 – McBurney’s Point (1), two thirds of the way between the umbilicus (2) and the ASIS (3)

Acute Appendicitis in Children

Whilst some cases can present classically, a high proportion of acute appendicitis in children will present in an atypical manner. Such presentations may include diarrhoea, urinary symptoms, or even left sided pain.

When examining a child with suspected appendicitis, as well as examining the gastrointestinal system, it is therefore also essential to examine the cardiorespiratory and urinary systems. In such cases, always ensure to perform a genital examination in all boys, to exclude testicular torsion or epididymitis.

Of note, any child <6yrs old who has had symptoms for >48 hours is significantly more likely to be suffering from a perforated appendix, therefore a period of active observation is often prudent in those with shorter histories.

Differential Diagnosis

There are a wide spectrum of potential differential diagnoses for suspected cases of appendicitis:

- Gynaecological – ovarian cyst rupture, ectopic pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease

- Renal – ureteric stones, urinary tract infection, pyelonephritis

- Gastrointestinal – inflammatory bowel disease, Meckel’s diverticulum, or diverticular disease

- Urological – testicular torsion, epididymo-orchitis

Specifically in children, differentials to consider include mesenteric adenitis, gastroenteritis, constipation, intussusception, or urinary tract infection.

Investigations

All patients with suspected appendicitis should have a urinalysis performed, to assess for any renal or urological cause*. For any woman of reproductive age, a pregnancy test is essential.

Routine blood tests, importantly FBC and CRP, should be requested to assess for raised inflammatory markers, as well as a clotting screen and group & save. A serum β-hCG may also be taken, if ectopic pregnancy still has not been excluded.

*Leucocytes can be present in the urine in low levels for those with an appendicitis, especially if the appendix lies on the bladder

Imaging

Clinical assessment alone, along with a suggestive biochemical picture, can be sufficient to diagnosis acute appendicitis, especially in paediatric cases.

However, given the wide differential diagnoses for many patients presenting with a potential acute appendicitis, further imaging is often require to confirm the diagnosis:

- Ultrasound – good first line investigation if the differential includes gynaecological pathology, especially with a transvaginal approach

- Also useful in children and pregnant patients as first line imaging, as can minimise radiation exposure

- Computed Tomography (CT) – Provides good sensitivity and specificity for an acute appendicitis, and can assess for alternative differentials including gastrointestinal and urological causes

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) – Can be useful as 2nd line imaging in children and pregnant women, if equipoise remains in the diagnosis

Figure 3 – CT imaging demonstrating an acute appendicitis

Risk Stratification Scores

Several risk stratification scores have been developed in an attempted to assist in the diagnosis of appendicitis, based on clinical and radiological evidence.

The RIFT study compared multiple risk prediction models, showing the best predictors for acute appendicitis were:

- Men – Appendicitis Inflammatory Response Score

- Women – Adult Appendicitis Score

- Children – Shera score

A risk score calculator using these parameters can be found here and can be used to aid clinical decision making

Management

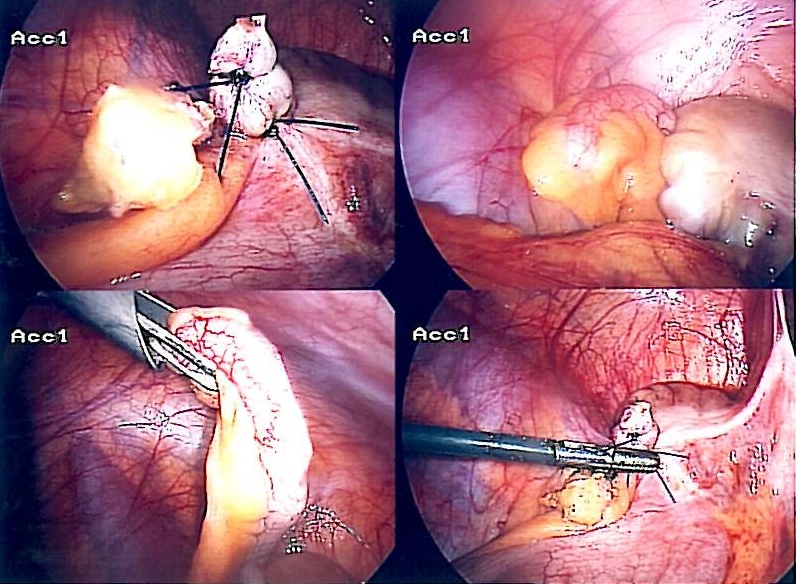

The current definitive treatment for appendicitis is laparoscopic appendicectomy (Fig. 4).

In certain cases, a non-surgical conservative approach may be trialled with antibiotics alone, such as in high-risk surgical candidate with uncomplicated appendicitis. However, whilst primary antibiotic treatment for simple inflamed appendix may be successful, it has a failure rate of 25-30% at one year. Indeed, a Cochrane analysis found that appendicectomy should remain the standard treatment for acute appendicitis.

If cases of an appendiceal mass, antibiotic therapy is favoured, with an interval appendectomy then performed approximately 6-8 weeks later

Appendiceal Mass

An appendiceal mass is an inflammatory phlegmon formed by the body in response to an acute appendicitis, whereby oedematous and adherent omentum and small bowel loops form around the appendix.

They can often be diagnosed pre-operatively, through both clinical examination and cross-sectional imaging. The majority of these cases should be treated conservatively initially with prolonged antibiotic courses, due to higher risks of visceral injury and other post-operative complications.

Patients can then be scheduled for an interval appendectomy at a later date, once the inflammation has subsided.

Surgical Intervention

A laparoscopic appendicectomy (Fig. 4) still remains the gold standard for treating an acute appendicitis. It provides a definitive treatment for appendicitis (compared to antibiotic therapy alone), it is a relatively low-risk procedure, and also allows direct visualisation of other organs (e.g. gynaecology pathology or Meckel’s diverticulum).

An open approach (classically via a Lanz incision) may still be used in certain cases and is routinely performed in some healthcare systems, however the laparoscopic approach has been shown to reduced hospital stay and permit earlier return to baseline activity

The appendix should routinely be sent to histopathology once removed, to assess for any underlying malignancy, as this is identified in around 1% of cases.

Complications

The mortality associated with acute appendicitis is low (between 0.1% to 0.24 %). However, complications can occur, including:

- Perforation – if left untreated the appendix can perforate and cause peritoneal contamination

- Surgical site infection – rates range between 3-10%, depending on degree of peritoneal contamination

- Appendiceal mass (as above)

- Abscess formation – severe cases or those with delayed presentation can develop intra-abdominal abscesses around the appendix itself

- Often requires treatment with intravenous antibiotics and radiologically-guided drainage, prior to any delayed surgical intervention

Key Points

- Acute appendicitis refers to inflammation of the appendix

- Patients often present with pain migrating from the central to right iliac fossa region

- In adults, diagnosis is often confirmed with ultrasound or CT imaging

- Management is typically with laparoscopic appendicectomy, however some cases can be treated conservatively with antibiotics alone