Tonsillitis is inflammation of the palatine tonsils as a result of either a bacterial or viral infection. The palatine tonsils are a concentration of lymphoid tissue within the oropharynx. Tonsillitis will often occur in conjunction with inflammation of other areas of the mouth, giving rise to the terms tonsillopharyngitis (the pharynx is also involved), and adenotonsillitis (the adenoids are also involved).

Pathophysiology

The size of the tonsils in relation to the oropharynx changes with growth and development. At birth the tonsils are fairly small; between the ages of 4 and 8, the tonsils are at their largest (1). Bearing this in mind, large clearly visible tonsils are not always the result of infection (see below under clinical features).

It is important to note that a significant proportion of infections of the upper respiratory tract, including tonsillitis and pharyngitis, are viral in origin (2, 3). Risk scores and indicative symptoms exist to help determine the difference between bacterial and viral causes (see below under clinical features).

Common viral causes are Adenovirus and Epstein Barr Virus, whilst Group A Streptococcus (Strep. Pyogenes) is the commonest bacterial organism, accounting for between 15 and 30% of cases depending on the study/age of child (4, 5).

Risk Factors

Smoking – either second hand smoke from parents or personal smoking in older children significantly increases the risk of tonsillitis (6).

Clinical Features

From History

The exact duration of symptoms varies depending on the causative organ, but in general will last between 5 and 7 days. Symptoms lasting longer than 7 days may be due to glandular fever.

- Odynophagia (in severe cases, patient is unable to even take liquids orally)

- Fever

- Reduced oral intake

- Halitosis

- New onset snoring (or even apneic episodes in severe cases)

- Shortness of breath

From Examination

- Red inflamed tonsils

- White exudate (pus) spots on the tonsils

- Cervical lymphadenopathy (most commonly the lymph nodes in the region of the upper third of the sternocleidomastoid muscle)

Antibiotics will most likely benefit a patient when their sore throat is caused by streptococcal bacteria. Two clinical scoring tools that can help to identify those in whom this is more likely are ‘Centor criteria’ and ‘FeverPAIN criteria’. Clinical practice can vary on which, if any, tool is used.

Centor Criteria

The Centor criteria was developed to try and differentiate between bacterial and viral tonsillitis based on clinical symptoms. There are four key criteria:

- Tonsillar exudate

- Tender anterior cervical lymphadenopathy or lymphadenitis

- Fever or history of fever

- Absence of cough

A score of 3 or more is highly suggestive of bacterial infection (40-60% likelihood) and a score of 2 or less suggests bacterial infection is unlikely (80% likelihood) (2).

FeverPAIN criteria

- Fever (during previous 24 hours)

- Purulence (pus on tonsils)

- Attend rapidly (within 3 days after onset of symptoms)

- Severely Inflamed tonsils

- No cough or coryza

Each element gives 1 point up to a maximum of 5. Score 0-1 suggests a 13-18% chance of streptococcal infection, 2-3 is 34-40% chance and 4-5 is 62-65% chance (2).

For a quick calculation of the FeverPAIN score follow this link: https://www.mdcalc.com/feverpain-score-strep-pharyngitis#evidence

Streptococcal Score Card

The streptococcal score card is specific to Group A Streptococci (GAS). The criteria include:

- Age 5-15

- Season (between late autumn and early spring)

- Fever (>38.3°C)

- Cervical lymphadenopathy

- Pharyngeal erythema, oedema, or exudate

- No viral URTI symptoms (eg. coryza, etc.)

5 criteria = 59% chance of GAS, 6 criteria = 75% (7).

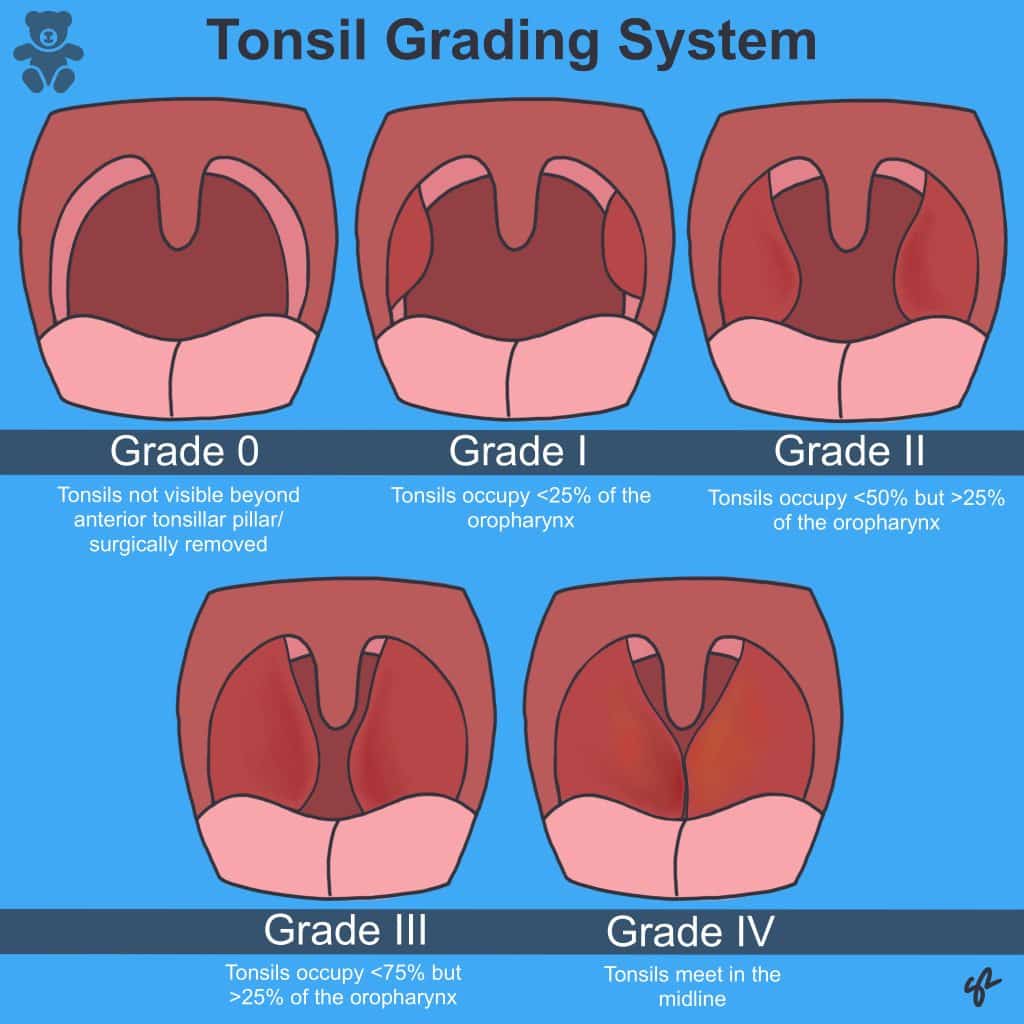

When examining the tonsils it is important to consider the normal development of the tonsils and their relative size (see above in pathophysiology). Tonsillar size is graded according to the proportion of the oropharynx occupied (Fig 1).

It is worth noting that grade II and III tonsils are at peak incidence at 4-5 years old. Until the age of 6, grade II tonsils predominate compared to grade I (1).

Enlargement of the tonsils in isolation is not necessarily a sign of infection, particularly in children with known recurrent episodes of tonsillitis. Bilaterally enlarged, somewhat rough, and irregular tonsils may represent the scarring and changes induced by recurrent infection.

Differential Diagnosis

- “Quinsy” or peritonsillar abscess – unilateral with swelling most prominent superior to the tonsil

- Pharyngitis – sore throat and difficulty swallowing in the absence of tonsillar inflammation may be termed pharyngitis (if due to a virus there may sometimes be vesicles visible)

- Glandular fever – Specific viral cause of tonsillitis which tends to have a longer symptom duration and may be associated with significant neck swelling and/or abdominal pain

- Tonsillar malignancy – lymphoma can occasionally present as unilateral enlargement of the tonsils; this is a feature in almost 73% of patients with tonsillar lymphoma. Unilaterally enlarged tonsils in association with other signs of malignancy is strongly suggestive of tonsillar lymphoma, however lymphoid hyperplasia and chronic tonsillitis can also cause asymmetrical tonsillar enlargement (8)

- Epiglottitis – These children will generally have very high fevers, stridor, significant respiratory distress and are usually drooling (because it is too painful to swallow). If you suspect epiglottitis, DO NOT EXAMINE THE CHILD. Leave them with their parents and seek the advice of a senior clinician (often with the assistance of an anaesthetist)

Investigations

The general consensus is that throat swabs are of limited value. They cannot differentiate between infective organism and colonisation (9, 2). Also, in the time it takes for a result to be made available, the child has usually either been successfully treated or the symptoms have resolved.

The decision to obtain blood samples will largely depend on whether or not the child is to be admitted. If this is the case, the following are useful:

- FBC – will show raised inflammatory markers with a neutrophil predominance in the case of bacterial tonsillitis

- LFTs – Patients with glandular fever may have deranged LFTs

- U+Es – Most patients with severe tonsillitis struggle to drink due to the pain and so it is important to check for significant dehydration/AKI

Management

Initial Management

The first key decision is whether the patient requires inpatient admission or not. The pointers below are merely guidelines and should not replace clinical judgement.

The following suggest severe tonsillitis or possibly an alternative diagnosis; they require urgent admission and assessment:

- Respiratory compromise (tachypnoea, low saturations, use of accessory muscles) or apnoeic episodes – these suggest that the tonsils are so large that they are affecting the child’s ability to ventilate. Alternatively, this may be an indication of possible epiglottitis (see above)

- Patients who are unable to eat or drink are at risk of dehydration – they should be admitted for treatment and monitoring until able to drink again

- Patients who have been treated with appropriate antibiotics in the community who are still not getting better should also be admitted for IV therapy and further investigation

Antibiotics

Patients who fulfill the centor criteria should be given antibiotics to cover Group A Streptococci. Typically, this will be a penicillin, usually Benzylpenicillin, dosed according to the child’s weight. Route depends on the degree of odynophagia (9) (10).

Although penicillins are the most common agent used in the UK, there is evidence to suggest that effectiveness of penicillin in providing complete resolution is diminishing and that cephalosporins may in fact be more effective (11).

Antibiotic therapy is usually continued for between 7 and 10 days and should be switched to oral penicillin V when the child is clinically improving and able to swallow

Co-amoxiclav is often avoided in cases of tonsillitis due to the small risk of permanent skin rash if the tonsillitis is due to glandular fever.

Analgesia

Paracetamol and Ibuprofen are effective pain relief in tonsillitis and can be alternated in order to give effective pain relief.

Topical analgesia, such as difflam (benzydramine) spray/mouthwash, can be helpful to reduce pain and allow the child to swallow oral analgesic agents.

Steroids

Steroid therapy is frequently used in children and adults with tonsillitis. A Cochrane review in 2012 concluded that resolution of pain at 24 hours was three times more likely following steroid administration (12). Although IV and IM steroids are often used in adults, the research in children mainly relates to oral steroids (13).

A meta-analysis in 2012 advocated the use of 0.6mg/kg oral dexamethasone (up to 10mg) as a single one-off dose for pharyngitis – this was found to be particularly effective in exudative or Group A Strep. positive disease (14).

Operative Treatment

Tonsillectomy is reserved for patients with recurrent, troublesome tonsillitis. The SIGN criteria are generally used to determine whether tonsillectomy is appropriate (15).

| In 1 year | 7 or more episodes of tonsillitis |

| In 2 years | 5 or more episodes per year |

| In 3 years | 3 or more episodes per year |

Complications

- Spread of the infection into the peritonsillar space may result in peritonsillar abscess (Quinsy)

- Spread into the retropharyngeal or parapharyngeal spaces is classified as a deep neck space abscess which requires prolonged IV antibiotics and sometimes surgical drainage

- Recurrent tonsillitis – not strictly a complication of an acute episode of tonsillitis, but children may often suffer from recurrent episodes of acute tonsillitis which can result in prolonged time off school (see above for indications for tonsillectomy)

Post streptococcal conditions

A detailed discussion of post streptococcal conditions is beyond the scope of this article, however a brief summary of the two main concerning sequelae are below:

Post streptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSGM)

PSGM is overwhelmingly more common in children (usually ages 6-8). Interestingly, certain strains of GAS are more likely to cause glomerulonephritis and certain strains are more likely to cause rheumatic fever (16).

PSGM has an incidence of around 1.7 per 100,000 and the classic triad of symptoms is hypertension, haematuria and oedema. There is also often proteinuria, but without true nephrotic syndrome.

Rheumatic Fever

Acute rheumatic fever (ARF) is now thankfully rare in developed nations (<1 per 100,000 in the US) but still poses a particular threat to paediatric populations in developing nations, most noticeably due to rheumatic heart disease.

ARF is an autoimmune response to GAS which typically affects children aged 5-14. It develops 2-5 weeks after the initial infection and causes a variety of symptoms including; prolonged fever, anaemia, arthritis, and pancarditis (17).

References

| (1) | A. Ackay, C. Kara and M. Zencir, “Variation in tonsil size in 4-to 17-year-old schoolchildren,” Journal of Otolaryngology, vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 270-274, 2006. |

| (2) | NICE, “Sore throat (acute),” NICE, Jan 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng84/chapter/terms-used-in-the-guideline . |

| (3) | A. Putto, “Febrile Exudative Tonsillitis: Viral or Streptococcal?,” Paediatrics, vol. 80, no. 1, 1987. |

| (4) | J. Windfuhr, N. Toepfner, G. Steffen, F. Waldfahrer and R. Berner, “Clinical practice guideline: tonsillitis I. Diagnostics and nonsurgical management,” European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, vol. 273, no. 4, pp. 973-987, 2016. |

| (5) | C. I. Timon, V. McAllister, M. Walsh and M. Cafferkey, “Changes in tonsillar bacteriology of recurrent acute tonsillitis: 1980 vs. 1989,” Respiratory medicine, vol. 84, no. 5, pp. 395-400, 1990. |

| (6) | A. E. Hinton, R. C. D. Herdman, D. Martin-Hirsch and S. R. Saeed, “Parental cigarette smoking and tonsillectomy in children,” Clinical Otolaryngology, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 178-180, 1993. |

| (7) | E. Wald, M. Green and B. K. Schwartz B, “A streptococcal score card revisited,” Pediatric Emergency Care, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 109-111, 1998. |

| (8) | A. Guimaraes, G. Carvalho, C. Correa and R. Gusmao, “Association between unilateral tonsillar enlargement and lymphoma in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Oncology Haematology, vol. 93, no. 3, pp. 304-311, 2015. |

| (9) | K. Stelter, “Tonsillitis and sore throat in children,” GMS Current topics in Otorhinolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, vol. 13, 2014. |

| (10) | V. Visvanathan and P. Nix, “National UK survey of antibiotics prescribed for acute tonsillitis and peritonsillar abscess,” The Journal of laryngology and otology, vol. 124, no. 4, pp. 420-423, 2010. |

| (11) | J. Caser and M. Pichichero, “Meta-analysis of cephalosporin versus penicillin treatment of group A streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis in children.,” Pediatrics, vol. 113, no. 4, pp. 866-882, 2004. |

| (12) | G. Hayward, M. Thompson, R. Perera, P. Glasziou, C. Del Mar and C. Heneghan, “Corticosteroids as standalone or add-on treatment for sore throat.,” Cochrane Database Systematic Review, vol. 17, no. 10, 2012. |

| (13) | K. Korb, M. Scherer and J. Chenot, “Steroids as Adjuvant Therapy for Acute Pharyngitis in Ambulatory Patients: A Systematic Review,” Annals of family medicine, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 58-63, 2010. |

| (14) | S. Schams and R. Goldman, “Steroids as adjuvant treatment of sore throat in acute bacterial pharyngitis,” Canadian family physician, vol. 58, no. 1, pp. 52-54, January 2012. |

| (15) | SIGN, Management of Sore throat and indication for tonsillectomy, SIGN, 2010. |

| (16) | T. Eison, B. Ault, D. Jones, R. Chesney and R. Wyatt, “Post-streptococcal acute glomerulonephritis in children:,” Pediatric Nephrology, vol. 26, pp. 165-180, 2010. |

| (17) | J. Lee, S. Naguwa, G. Cheema and E. Gershwin, “Acute rheumatic fever and its consequences: A persistent threat to developing nations in the 21st century,” Autoimmunity reviews, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 117-123, 2009. |

| (18) | R. J. Gaffey, D. J. Freeman, M. A. Walsh and M. T. Cafferkey, “Differences in tonsil core bacteriology in adults and children: a prospective study of 262 patients,” Respiratory medicine, vol. 85, no. 5, pp. 383-388, 1991. |

| (19) | A. L. Bisno, “Acute Pharyngitis,” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 344, pp. 205-211, 2001. |

| (20) | R. M. DeDio, T. L. W. C and M. LK, “Microbiology of the Tonsils and Adenoids in a Pediatric Population,” JAMA otoloaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, vol. 114, no. 7, pp. 763-765, 1988. |

| (21) | M. S. Israel, “The Viral flora of enlarged tonsils and adenoids,” The Journal of Pathology, vol. 84, no. 1, pp. 169-176, 1962. |

| (22) | P. J and W. JA, “An evidence-based review of peritonsillar abscess,” vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 136-145. |

Authors:

1st Author: Dr Thomas Stubington

Senior review: Dr Raguwinder Sahota, Advanced ENT specialist registrar