Introduction

Dehydration occurs when fluid output is greater than fluid input. Infants and children are at greater risk of developing dehydration than adults due to higher metabolic rates, inability to communicate thirst or self-hydrate effectively and greater water requirements per unit of weight (1,2). To add to this, many common conditions in younger age groups can result in dehydration. This results in dehydration being a common presentation for children and infants in both primary and secondary care. It is important to be able to assess for and effectively manage dehydration as failure to do so may result in severe complications including electrolyte imbalances and end organ failure from hypovolaemic shock.

Aetiology

It is useful to think of the causes of dehydration as falling under one of two categories.

- Inadequate intake of fluid

- Excessive loss of fluid

Causes of inadequate fluid intake include:

- Structural malformation – e.g. tongue tie, cleft lip and/or palate, micrognathism. These will most likely be picked up and managed during the neonatal period.

- Discomfort – e.g. oral ulcers, tonsillitis, viral pharyngitis, stomatitis.

- Respiratory distress – In order to feed and drink, it must be possible to temporarily stop breathing. This is very difficult if already short of breath.

- Neglect – Though uncommon and rarely deliberate, poor fluid intake may result from inadequate feeding in neonates and infants and poor education or supervision in children.

Causes of excessive fluid loss include:

- Diarrhoea and/or vomiting – The most common cause of dehydration in children in the UK and worldwide (2). Can present in a variety of common paediatric conditions such as gastritis, gastroenteritis, pyloric stenosis, mesenteric adenitis, acute appendicitis and diabetic ketoacidosis.

- Excessive sweating – e.g. strenuous or prolonged physical activity, hot weather, pyrexia.

- Polyuria – Diabetes mellitus (most commonly type 1 in paediatrics), diabetes insipidus

- Burns

Clinical Features

History

A good history will provide information as to whether or not an infant or child may be dehydrated, as well as the underlying cause. It is important to consider:

- Recent or ongoing fluid losses

- Vomiting, diarrhoea, excessive sweating, polyuria

- Quantity of fluid loss

- In a patient who has vomited; how many episodes of vomiting over how long and how much fluid is in each vomitus

- Is the patient still eating and drinking? If so how much?

- Along with asking about fluid losses, this will give a rough estimate of the current fluid status of the patient.

- Is the patient still urinating? If so are they passing the same quantity urine and as often as when they are healthy? Is the urine concentrated or diluted?

- Polyuria may cause dehydration and give a clue to the underlying cause e.g. diabetes mellitus type 1, diabetes insipidus, adrenal insufficiency. Oliguria or anuria could have many causes, one of which is severe dehydration.

Examination

NICE have produced the following guidelines for assessing dehydration and shock (4).

| No clinically detectable dehydration | Clinical dehydration | Clinical shock | |

| Symptoms

(remote and face-to-assessments) |

Appears well | Appears to be unwell or deteriorating | – |

| Alert and responsive | Altered responsiveness (for example, irritable, lethargic) | Decreased level of consciousness | |

| Normal urine output | Decreased urine output | – | |

| Skin colour unchanged | Skin colour unchanged | Pale or mottled skin | |

| Warm extremities | Warm extremities | Cold extremities | |

| Signs

(face-to-face assessments) |

Eyes not sunken | Sunken eyes | – |

| Moist mucous membranes (except after a drink) | Dry mucous membranes (except for ‘mouth breather’) | – | |

| Normal heart rate | Tachycardia | Tachycardia | |

| Normal breathing pattern | Tachypnoea | Tachypnoea | |

| Normal peripheral pulses | Normal peripheral pulses | Weak peripheral pulses | |

| Normal capillary refill time | Normal capillary refill time | Prolonged capillary refill time | |

| Normal skin turgor | Reduced skin turgor | – | |

| Normal blood pressure | Normal blood pressure | Hypotension (decompensated shock) |

Of the above symptoms and signs, the following are RED FLAGS:

- Appears unwell or deteriorating

- Altered responsiveness

- Sunken eyes

- Reduced skin turgor

- Tachycardia

- Tachypnoea

The following may be present in hypernatraemic dehydration, whereby proportionally more water than sodium is lost from the body (4):

- Jittery movements

- Increased muscle tone

- Hyperreflexia

- Convulsions

- Drowsiness or coma.

Management

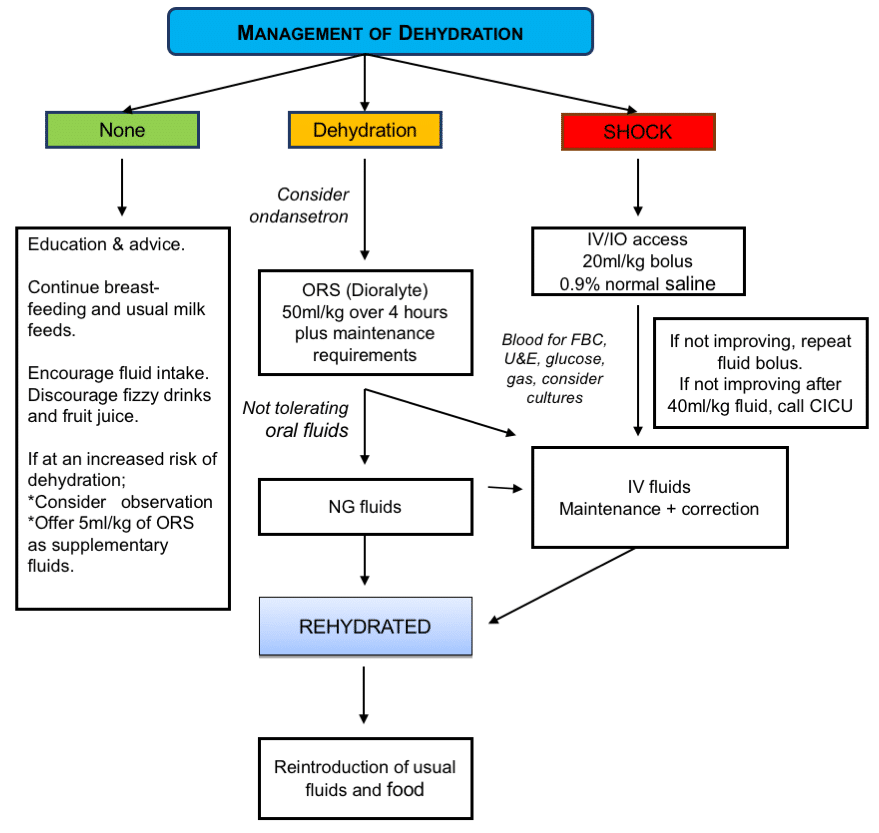

Figure 1 provides an overview for assessing and managing dehydration. Any reversible causes of dehydration should be investigated and managed to prevent further fluid losses.

Figure 1: Assessment and management of dehydration (Reproduced with permission from Dr Hafizah Salleh, paediatric doctor)

Rehydration

Depending on the clinical picture, rehydration will be achieved via oral rehydration solution or IV fluids. All patients should have fluid balance charts to assess fluid input, ongoing losses and urine output.

Oral rehydration solution should be given in small volumes at frequent intervals. Regular reassessment will be required to determine its effectiveness.

If a child is clinically dehydrated but able to tolerate enteral fluids (PO/NG) then a 50mL/kg fluid deficit is calculated. This is given orally, along with maintenance fluids, over 4 hours as oral rehydration solution. For example, a child who weighs 10kg will require 500mL AND maintenance fluid over 4 hours.

IV fluids should be given in the following circumstances (4):

- Shock is suspected or confirmed

- A child with red flag symptoms or signs (see assessment table) shows clinical evidence of deterioration despite oral rehydration therapy

- A child persistently vomits the oral rehydration solution, given orally or via a nasogastric tube.

In a child with shock, give a rapid 20ml/kg bolus 0.9% sodium chloride, call for senior help and reassess the patient (Caution advised in DKA or underlying heart condition when 10mL/kg bolus should be considered)

- If inadequate or no response, give another rapid 20ml/kg sodium chloride bolus and consider other causes of shock.

- If a third bolus is required, consider input from paediatric intensive care

- Once an adequate response to bolus therapy has been achieved (i.e. the patient is no longer clinically in shock) start IV fluid deficit correction as shown below(4)

In a child who is not in shock, yet requires IV fluids, deficit correction should be achieved as follows (note: there are varied methods for calculating fluid deficit and so this information should serve as a guide for learning. Use up to date national guidance in your area or hospital for patient management).

- If there is a recent weight done prior to admission, the fluid deficit can be taken as the weight loss compared to current weight.

- For example, if weight done 2 days ago was 15.5 kg and current weight is 15 kg, the fluid deficit can be taken as 500 ml (500 gram lost = 500 ml lost).

- However, if there are signs of clinical dehydration, and there is no recent weight, the fluid deficit is calculated as: weight (kg) x % replacement x 10. This is given over 48 hours.

- The % replacement (also known as % dehydration) should be assumed to be 10%, if dehydrated.

- For example, a child who weighs 12 kg will require 1200 ml (12 x 10 x 10) over 48 hours, or 600 ml each day in addition to their maintenance.

- Aim to correct fluid deficit over 48 hours with 0.9% sodium chloride and 5% dextrose

Estimate of fluid deficit

Weight (Kg) x % dehydration x 10

Reassess the patient regularly to monitor response

U+Es and plasma glucose should be measured before starting deficit correction and regularly over the 48 hour period. Electrolyte imbalances and/or hypoglycaemia may require alterations to the type of fluid used.

Significant ongoing losses through, for example, vomiting or diarrhoea should be documented on the patient’s fluid balance chart and replaced in addition to fluid deficit correction.

In a patient with hypernatraemic dehydration, call for senior paediatric help. Fluid will need to be replaced slowly over 48 hours in order to avoid cerebral oedema. Regular monitoring of U+Es should be done to ensure plasma sodium does not fall by a rate greater than 0.5mmol/L/hour.

Fluid Management after Rehydration (4)

- Encourage breastfeeding and other milk feeds

- Encourage fluid intake

- Discourage fruit juices and carbonated drinks

In children at increased risk of dehydration recurring, consider giving 5 ml/kg of oral rehydration solution after each large watery stool. These include:

- Children younger than 1 year, particularly those younger than 6 months

- Infants who were of low birth weight

- Children who have passed more than five diarrhoeal stools in the previous 24 hours

- Children who have vomited more than twice in the previous 24 hours.

Preventing Dehydration

Parents should be given the advice outlined in ‘Fluid management after Rehydration’ following any treatment for dehydration.

In a patient who is nil by mouth for a surgical procedure or not tolerating enteral fluids but not yet dehydrated, maintenance fluids should be prescribed as follows over a 24 hour period using 0.9% sodium chloride and 5% dextrose (5):

- 100ml/kg for first 10kg bodyweight

- 50ml/kg for second 10kg bodyweight

- 20ml/kg for every kg above 20kg bodyweight

For example, a 25kg child would require the following:

First 10 kg = 1000ml (10 x 100mL)

Second 10kg = 500ml (10 x 50mL)

Last 5kg = 100ml (5 x 20mL)

Total 1600ml over 24 hours (1600/24: rate = 67ml/hr). Remember to monitor electrolytes to determine if anything such as potassium should be added to the fluids.

Note: Over 24 hours, males rarely need more than 2500mL and females rarely need more than 2000mL (5).

References

| 1. | D’Anci KE et al (2006) Hydration and Cognitive function in children. Nutr Rev. 2006 Oct;64(10 Part 1):457-64 |

| 2. | Vega RM, Bhimji SS (2017) Dehydration, Pediatric. StatPearls PMID: 28613793 |

| 3. | Willock J, Jewkes F (2000), Making Sense of Fluid Balance in Children, Paediatric Nursing 12,7 37-42 |

| 4. | NICE (2009), Diarrhoea and vomiting caused by gastroenteritis in under 5s: diagnosis and management. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg84/resources/diarrhoea-and-vomiting-caused-by-gastroenteritis-in-under-5s-diagnosis-and-management-975688889029 Accessed 24/11/2016 |

| 5. | NICE guideline NG29: Intravenous fluid therapy in children and young people in hospital (Dec 2015). Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng29/chapter/Recommendations#fluid-resuscitation-2 |