Disclaimer: The following article should be used for educational purposes only. It should not be used to guide or alter the clinical management of a patient.

Introduction

Choking still remains a cause of infant mortality and is most common in the 1 to 4 age group (1). As a paediatrician and a bystander it is important to know how to manage a choking child to prevent potential collapse.

Epidemiology

80% of episodes occur in the 1-3 age groups with the peak frequency occurring between 1-2 years. (2)

Pathophysiology

Physical obstruction of the airway can be caused by obstruction due to ingestion of food objects, small toys, vomit or bacterial infection of the upper airway.

Risk Factors

- Playing with small parts

- Unsupervised play and eating

- Children with decreased consciousness

Clinical Features

From the clinical history and examination look for:

- Playing with toys that have small parts

- Unsupervised play/ eating

- Eating prior to event

- Poor swallow/ poor coordination of suck

- Previous episodes of aspiration/ choking.

Differential Diagnosis

Important differentials with salient features to help to differentiate

- Acute epiglottis– sitting forward, drooling, toxic looking, temperature.

- Croup– coryzal symptoms, cough associated, improved with steroids/ adrenaline nebuliser.

- Laryngomalacia– present from an early age, improves with age.

- Whooping cough– unimmunised child, cough associated, coryzal symptoms may have associated temperature.

- Reduced GCS– can cause stridor- history suggesting cause for reduced GCS. Not responding to pain.

Acute epiglottis, croup and laryngomalacia are important for children with known or suspected infections

Management

If a foreign body can be seen easily in the mouth and is accessible it should be removed, but at the same time taking great care not to push it further into the airway! Do not however perform a blind finger sweep as this can easily push the foreign body further into the airway.

The airway should only be cleared if:

- The diagnosis of foreign body air obstruction is clear cut. For instance, the incident was witnessed and coughing has become ineffective, resulting in dyspnoea, apnoea and loss of consciousness

- In an unconscious child the process of head tilt chin lift has failed to open the airway due to the foreign body (3)

Initial management

If the child is coughing, this should be encouraged.

The child’s own spontaneous cough is much more effective than any external manoeuvre. If the child is coughing effectively they should be able to breathe, speak and cry between bouts of coughing.

No intervention is required until the child cannot cry, speak, breathe, evidence of cyanosis or decreased consciousness.

Definitive and Long-term management

Infants

In this age group a combination of back blows and chest thrusts is the recommended practice. To begin with five back blows (figure 1) are performed, checking after each one to see if the foreign body has been expelled.

Place infant on forearm- face down with head pointing towards the ground. With the hand of the rescuer supporting the jaw (keeping it open). With the free hand five back blows are given.

Figure 1. Demonstration of back blows

If this does not improve the situation the infant is turned over (still head down) and placed along the rescuer’s arm. Then 5 chest thrusts are performed (Figure 2). Two fingers are placed at the lower edge of the sternum (below nipple line). If the infant is too large then they can be placed on the lap of the rescuer.

Figure 2. Demonstration of chest thrusts used in choking infant

Children

If the child is coughing this should be encouraged. Back blows are the first step with the child supported in a leaning forward position. This should be attempted as 5 back blows with hand placement between shoulder blades, checking after each blow to see if the foreign body has been expelled (figure 3).

Figure 3. Demonstration of back blows

If this fails the Heimlich manoeuvre should be performed (figure 4). If the child is standing the rescuer should move to a position behind the child. If there is a large height difference the rescuer is able to kneel behind the standing child. One hand is placed under the xiphisternumin the shape of a fist- the other is placed over the fist and both are thrust sharply into the abdomen. This is repeated 5 times unless the object is expelled.

Figure 4. Demonstration of abdominal thrusts used in choking

After each blow/thrust the airway should be checked to see if the object has been expelled. If abdominal thrusts have been performed the child must be assessed for abdominal injury.

If the child becomes unconscious it is important to call for help.

Place the child on a flat surface (supine). Assess airway for evidence of visible object causing obstruction. Open the airway and given 5 inflation breaths. Then continue the BLS algorithm as per the Basic Life Support section.

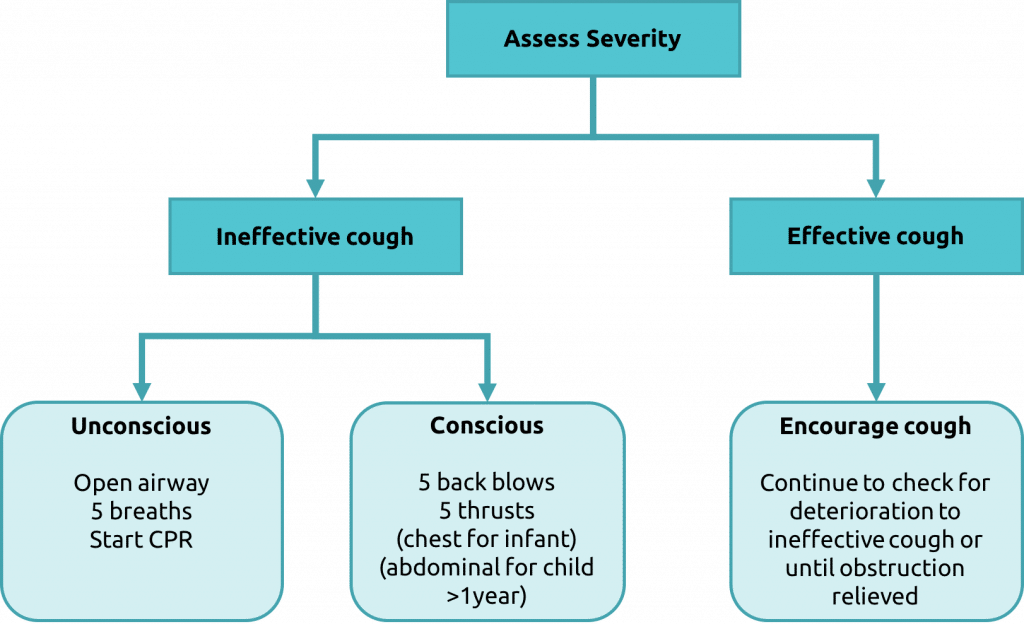

Each time breaths are attempted look in the mouth for evidence of foreign body and remove it if visible. If effective breathing commences, place in the recovery position and monitor. The choking algorithm can be followed in figure 5.

Figure 5. Algorithm for the management of choking as per APLS guidelines. Figure adapted (4)

Complications

If choking progresses and the object is not able to be dislodged, the child may progress to a state of unconsciousness and progression down the BLS algorithm may be required. Outcomes could include hypoxic brain injury or even death.

References

| (1) | Hayes NM1,Chidekel A. Pediatiric Choking. Del Med J. 2004 Sep; 76(9):335-40. |

| (2) | Ciftci AO, Bingol-Kologlu M, Senocak ME, et al; Bronchoscopy for evaluation of foreign body aspiration in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2003 Aug 38(8):1170-6. |

| (3) | Advanced Life Support Group. Advanced paediatric life support—the practical approach, 5th London: Wiley- Blackwell 2014- management of choking based on information taken from the APLS manual. |

| (4) | Advanced Life Support Group. Advanced paediatric life support—the practical approach, 5th London: Wiley- Blackwell 2014 |

Authors:

First draft: Dr Vicki Currie

Senior review: Dr Helen Stewart (Paediatric specialist registrar)