Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects a person’s social interaction, communication and behaviour.

It is usually diagnosed in childhood, with some of the key symptoms being present from before the age of three (although diagnosis may be much later than this).

In this article, we shall look at the pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of autism.

Epidemiology

The UK prevalence of autism spectrum disorder is around 1% and is more common in boys than girls.[1]

It is more prevalent in children that were born prematurely, although the reason for this is not yet clear.[7] Other factors thought to increase the risk of developing ASD in the future include perinatal hypoxia and advanced maternal or paternal age.[8]

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology of autism spectrum disorder is multi-factoral and currently poorly understood. It is a feature of some genetic syndromes such as fragile X syndrome, tuberous sclerosis and Angelmann syndrome.

Twin studies have shown a strong genetic aetiology, but it is only recently with the development of microarray testing that specific genes are beginning to be identified.[2] Even with recent advances, chromosomal analysis only gives a diagnosis in around 5% of cases and microarray can pick up a further 10% of cases.[3] It is likely that multiple genes are involved, alongside environmental factors.

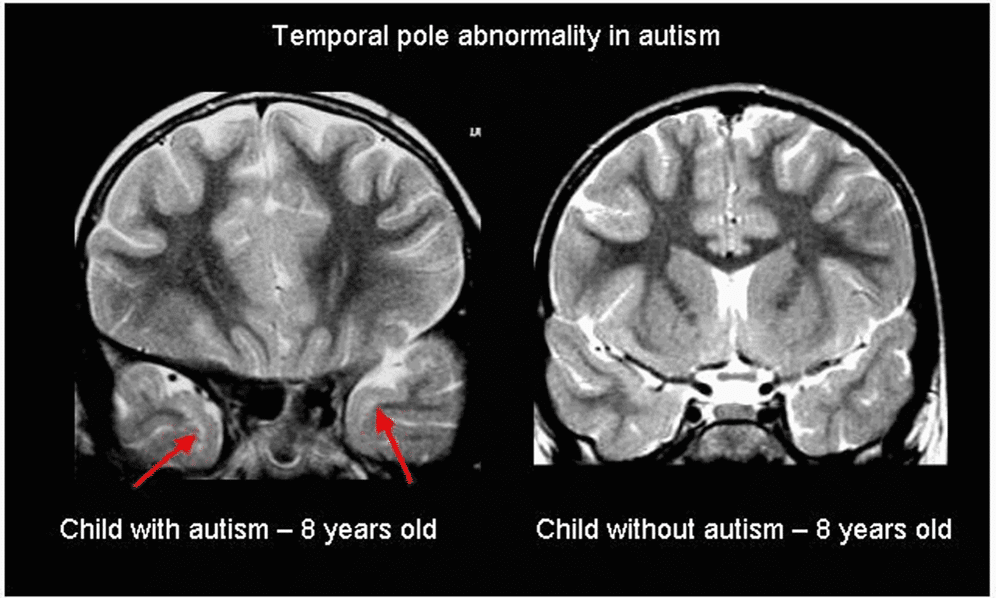

The neuropathology of autism remains poorly defined, with no particular region of the brain or neuropathological mechanism identified. Although post-mortem studies and studies using neuroimaging have detected structural changes of the brain, it is not well understood how these differences can explain the resulting symptoms. [4]

Fig 1 – Structural abnormalities have been demonstrated in those with autism, but it is unclear how this produces the features of the disorder. This is an example of typical sub-cortical hyperintensities on T2-weighted coronal images localized in the temporal poles observed in children with autism (red arrows) and a normal image of a control child without autism.

Clinical Features

The diagnosis of autism is largely from the history, and depends on impairments in three key areas [5]. There is a NICE guideline covering recognition, referral and diagnosis of autism in children, which includes detailed descriptions of symptoms (NICE Guideline CG128).

Abnormality of Social Interaction

This includes the most well-known symptom of autism – poor eye contact; but it can also include failure to use facial expression or body language during social interactions; particularly with strangers.

It also includes problems making friends with peers, and difficulty in reading social situations (such as failing to pick up on others emotions).

Impaired Social Communication

This includes delay or failure to develop either spoken language or sign language to communicate with others. Also can be a failure to initiate or continue conversations.

Included in this is the abnormal use of language; either with idiosyncrasy or stereotyped language (e.g. echolalia – repetition of another person’s spoken words) or abnormal intonation, pitch, rate or rhythm of speech.

Restrictive or Repetitive activities

Children display preoccupations with unusual subjects (for example, traffic lights) and/or in an atypical way, resulting in an all-encompassing obsession with the minutiae of a subject.

It also includes a need for routine, with great upset if this is disrupted. There may be a need for certain rituals to be performed by themselves or others in a specific way as part of this routine (for example when going to bed there must be certain toys placed in specific places, the light switch touched a certain number of times and then the blankets placed in a certain way before the child will sleep).

There may be abnormal preoccupations with toys and other materials – for example spinning wheels on cars for the vibration it makes, or licking metal objects.

There may be “motor mannerisms” with the classical hand-flapping or other such repetitive and compulsive movements, which can occur more when the child is excited or upset.

Other Features

Children with autism may also present with sensory issues that can impact significantly on their health and or quality of life. They may only eat certain foods (due to not liking the texture or needing it all to be a certain colour) and may have a severely restricted diet. They may not tolerate their hair being cut or their teeth being brushed, and thus it can be a challenge for parents to maintain their child’s personal hygiene.

They may not tolerate loud noises or seem to have a very high pain threshold. They may self-harm (head banging or hitting themselves) as a part of their motor mannerisms (for example pinching themselves repeatedly) or as an outlet when frustrated.

Examination

The examination is usually unremarkable, but its purpose is to exclude any underlying medical or genetic conditions. NICE guidelines [6] recommend a general examination, including looking for:

- Skin stigmata of neurofibromatosis or tuberous sclerosis using a Wood’s light.

- Signs of injury, for example self-harm or child maltreatment.

- Congenital anomalies and dysmorphic features including macrocephaly or microcephaly.

Fig 2 – Facial angiofibromas in a patient with tuberous sclerosis

Diagnosis of Autism

Not all of the above features have to be present to make a diagnosis, however there should be features present from all three categories and one of the following features present from before the age of three years:

- A lack of social attachments.

- Abnormal / delayed receptive or expressive speech development.

- Abnormal or lack of symbolic play (e.g. having a pretend tea party).

Differential Diagnosis

In a case of suspected autism, the other important diagnoses to consider include:

- Learning difficulties – It can be very difficult to diagnose autism in a child with learning difficulties, although the two can co-exist – what is important to determine is if the behaviours exhibited are in line with the child’s developmental age or would be explained by the comorbid diagnosis of ASD.

- Attachment disorders – Due to the absence of adequate social and emotional interaction between the child and parent there is failure to develop a bond between them. The child may fail to seek comfort when distressed or fail to be appropriately worried when picked up by someone unfamiliar and actively seek attention from strangers.

- Rett’s Syndrome – A rare genetic syndrome occurring mostly in girls. It presents in affected girls who develop normally for the first 6 months, but then by 18 months of age begin to regress and lose skills. Marked features include speech delay and repetitive hand movements, in particular hand-wringing and flapping.

- Schizophrenia – Extremely rare in children, it can present with disordered language and odd behaviours that can also be a feature of ASD. The diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia include hallucinations and delusions which are not a feature of ASD.

- Specific language disorders – There are now separate diagnostic criteria for conditions that affect a child’s social speech and communication only. Thus this is a diagnosis that is more likely to be made by a Speech and Language therapist, as they include only the use of specific restrictions and impairments of the use of social language.

Investigations

Autism spectrum disorder is a clinical diagnosis, with no specific blood or imaging tests currently available.

The main focus of investigation is to gather information to support or dismiss a diagnosis. The symptoms should be consistently present in different environments (i.e. both at home and at school) – thus at the very least a report of how the child functions at school is usually sought and a school observation may be performed.

The diagnosis should be made through a multi-disciplinary team from various agencies, and then a meeting held with all interested parties (the MDT team, parents and teachers) to come to a consensus. The MDT should ideally consist of an educational psychologist and speech therapist, as well as either a Community Paediatrician or Child Psychiatrist.

Management

Sometimes, for children on the milder end of the spectrum, the diagnosis alone is sufficient to explain the child’s behaviour and allow the adults around them to meet their individual needs. It also allows families to access certain modes of support, such as parent support groups and some community-based services.

There are no medications to specifically treat autism, although medication may be required to treat other co-morbid conditions such as ADHD. Very rarely in older children with marked aggression, antipsychotic medications have been used – but these would be under the direction of a child psychiatrist.

Management techniques include behavioural management and educational measures:

- Behavioural management strategies – visual timetables, preparation and explanation for changes in routine.

- Educational measures – Schools can access ‘Higher Needs Funding’ based on the needs of the individual child, but a diagnosis is needed for an ‘Education, Health and Care Plan’ (EHCP, previously known as a statement of special educational need). These detail the needs of the child and how the education environment will seek to meet those. Most children are educated in mainstream schooling but some will require the environment of a special school to support them appropriately.

Adequate treatment of co-morbid conditions is also important. The most common co-morbid conditions include ADHD, sleep disorders, learning disabilities and mental health conditions (such as depression or anxiety). Appropriate management of these conditions will help with behaviour management and allow the child to access education to the best of their ability.

Prognosis

The features of autism exist on a spectrum. At one end, there will be children who are able to learn ways to manage their difficulties and live independent lives in successful careers with children of their own. At the other end are children who are so severely affected that they never achieve independent living and may require supported accommodation after they reach adulthood.

Further resources

For up to date research in autism check out https://www.autismresearchcentre.com/

References

| (1) | Baird G1, Simonoff E, Pickles A, Chandler S, Loucas T, Meldrum D, Charman T. Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South Thames: the Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP). 2006 Jul 15; 368(9531):210-5. |

| (2) | Bailey A1, Le Couteur A, Gottesman I, Bolton P, Simonoff E, Yuzda E, Rutter M. Autism as a strongly genetic disorder: evidence from a British twin study. Psychol Med. 1995 Jan;25(1):63-77. |

| (3) | Yiping Shen et al Clinical Genetic Testing for Patients With Autism Spectrum Disorders Pediatrics. 2010 Apr; 125(4): e727–e735. |

| (4) | Schmitz C1, Rezaie P. The neuropathology of autism: where do we stand? Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2008 Feb;34(1):4-11. Epub 2007 Oct 26. |

| (5) | Childhood autism from ICD-10 1993 by WHO |

| (6) | Autism spectrum disorder in under 19s: recognition, referral and diagnosis NICE Guidance Clinical guideline [CG128] Published date: September 2011 |

| (7) | Kuzniewicz MW1, Wi S2, Qian Y2, Walsh EM2, Armstrong MA2, Croen LA2. J Pediatr. Prevalence and neonatal factors associated with autism spectrum disorders in preterm infants. 2014 Jan;164(1):20-5. Epub 2013 Oct 22. |

| (8) | Kolevzon A, Gross R, Reichenberg A. Prenatal and Perinatal Risk Factors for Autism A Review and Integration of Findings Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(4):326-333. |

| (9) | Morgan S. Antipsychotic drugs in children with autism. BMJ 2007; 334 |