The RCPCH defines Child Protection as “the process of protecting individual children identified as either suffering, or likely to suffer, significant harm as a result of abuse or neglect. It involves measures and structures designed to prevent and respond to abuse and neglect. Child abuse involves acts of commission and omission, which results in harm to the child. The four types of abuse are physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse and neglect. (1)

History

Until the 18th century children were regarded as possessions of their parents and as such parents had the right to treat them as they wished. Indeed, legislation was introduced to protect animals before children!

It was not until after World War II that child abuse was acknowledged there was recognition that children needed protection. Society was slow to accept that carers could deliberately harm children they were responsible for.

It was not until the 1970s that physical abuse was recognised as a common occurrence and a pathway for its management was introduced. It took another 10 years for the problem of sexual abuse to be highlighted.

Many lessons, unfortunately, have been learnt from tragedies leading to public enquiries, local case reviews and research. (2) The recognition and management of child abuse has improved significantly over the last 50 years however the development of systems to safeguard children is an ongoing process.

Prevalence

The true prevalence of child abuse is difficult to determine largely due to differing perceptions as to what constitutes child abuse and the research method used. What defines the definition of child abuse changes over time, within societies and even within families. Data studies rely on child abuse being identified and reported by professionals.

Child abuse is a global problem with serious life-long consequences. International studies reveal that a quarter of all adults report having been physically abused as children and 1 in 5 women and 1 in 13 men report having been sexually abused as a child. (3)

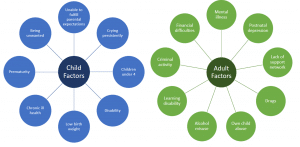

Risk Factors

Many risk factors have been identified that place children at higher risk for maltreatment. It is important to remember that although certain factors relating to the child places them at higher risk the child is the victim and should never be blamed for any maltreatment.

Types of child abuse

Historically ‘the battered baby’ where physical injuries inflicted on the child by an adult was considered child abuse. Now it is recognised that child abuse can be categorised into four separate areas- physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse and neglect. Often children present with one form of abuse, however it is likely that they are also suffering from a combination of several forms.

Physical abuse

Physical abuse involves causing physical harm to a child and is not exclusive to hitting, shaking, burning, drowning, suffocating or throwing. Determining the prevalence of physical abuse is complicated by poor definitions of what constitutes abuse and differing attitudes towards the use of physical punishment. Few studies have investigated physical abuse. The NSPCC found, in one large study, that a quarter of adults sampled had experienced serious physical violence, including being hit with an object. (2)

Young children, especially those under 2 years, are at highest risk of physical abuse.

Although the majority of injuries sustained are accidental, a careful history and full examination must be undertaken in all children to differentiate from those which are deliberately inflicted.

Features of the history which should increase the clinicians suspicion of non-accidental injury (NAI) are:

- Mechanism of injury was not compatible with the injury sustained

- The child’s developmental stage was inconsistent with the injury presented

- The child sustained a significant injury with little or no explanation

- Inconsistent histories were given

- There was a delay in presenting the child to health care providers

- Recurrent injuries

- The parents reaction was not appropriate to the situation – too concerned, aggressive, elusive, vague.

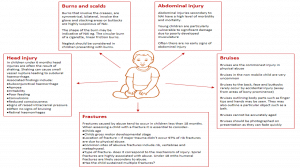

Presentation of Physical Abuse

Figure 2 – A detailed overview of the different ways in which physical abuse can present

Investigation of physical abuse:

| Presentation | Differential diagnosis | Investigation |

| Bruising | · Bleeding disorder

· Birth marks (congenital dermal melanocytosis, capillary haemangioma, congenital melanocytic naevi) · Vasculitic disorders · Infection (meningococcal septicaemia, HSP) · Drug related (NSAIDS) · Erythema nodosum · Malignancy · Striae · Contact dermatitis

|

Coagulation screen

Full blood count |

| Fractures | · Birth injury (clavicular fracture)

· Infection (osteomyelitis) · Malignancy · Osteogenesis imperfecta · Nutritional – vitamin D deficiency · Copper deficiency

|

Full skeletal survey

CT scan Bone biochemistry |

| Presentation of physical abuse in child less than 2 years | Full skeletal survey

CT head Expert ophthalmological examination Coagulation screen |

Neglect

Neglect is defined as “the persistent failure to meet the childs basic physical or psychological needs that is likely to result in the serious impairment of the childs health or development”t. (4)

Neglect is the commonest form of child abuse and the most common reason for a Child Protection Plan. It can be argued that neglect plays a part in all forms of child abuse. Neglect has the potential to be life-threatening and should be considered as severe as all other forms of abuse. However, it is important to recognise neglect may be unintentional. Although neglect is often associated with poverty it also occurs in affluent families.

The effects of neglect appear to be cumulative and long lasting. It can affect the child physically (inadequate supervision, nutrition and healthcare), emotionally and socially. Neglect needs to be recognised early to limit long term effects.

Presentation of neglect:

- Medical

-

- Unimmunised

- Failure to attend appointments

- Poor compliance with medication

- Failure to seek appropriate, timely medical advice

-

- Nutritional

-

- Faltering growth due to failure to provide an appropriate and or sufficient diet

- Obesity due to failure to control diet and lifestyle

-

- Emotional

-

- See emotional abuse section

-

- Educational

-

- poor school attendance

-

- Physical

-

- inadequate hygiene- dirty and smelly

- severe and or persistent infestations/infections

- inappropriate clothing for the childs size and weather

-

It may be difficult to distinguish between neglect and poverty, however, consideration should be taken to how others in similar situations meet the needs of their children

- Failure to supervise

-

- Frequent A&E attendances

- Injury that suggests lack of care such as sun burn, scalds and burns, falls, significant injury

- Ingestion of harmful substances

-

Emotional abuse

Emotional abuse is defined as “persistent, non-physical, harmful interactions with the child by the care-giver”. (4)

Emotional abuse, which also includes emotional neglect, is the hardest form of abuse to identify and evidence, however it is no less harmful to the child than the other categories of abuse.

Symptoms of emotional abuse

| Infant | Toddler | School child | Adolescent |

| Developmental delay

Poor sleep Feeding difficulties Persistent Crying Irritable Apathetic |

Difficult/violent behaviour

Delayed social and language skills

|

Poor attendance

Truancy Antisocial behaviour Academic failure |

Depression

Self harm Relationship difficulties Substance abuse Criminal activity Eating disorders Aggressive behaviour |

It is imperative that parent-child interactions are observed and documented in a variety of environments in order to fully assess and evidence potential abuse.

Sexual abuse

Sexual abuse is defined as “physical contact, including penetrative and non-penetrative acts, exposure to sexually explicit material and child sexual exploitation” (4)

Although sexual abuse is managed by paediatricians with specific training any clinician working with children needs to be able to recognise signs of sexual abuse and know what to do. Any suspicion of sexual abuse must be acted upon.

Children having been sexually abused present in the following ways:

- Allegation – a child may disclose abuse to anyone at any time

- Pregnancy

- STI

- Ano-genital injury

- Unexplained vaginal bleeding

- Unexplained rectal bleeding

- Recurrent vaginal discharge

- Soiling, bowel problems, enuresis

- Behavioural difficulties

- Any child in close proximity with an adult identified as a risk to children

- When the perpetrator is a child

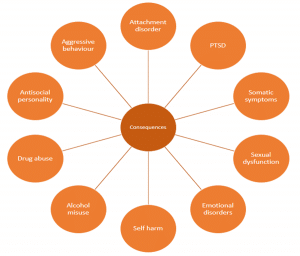

Consequences of child abuse

Child abuse causes immediate and long term negative consequences for the childs health and development. The severity of these consequences is influenced by:

- The type and form of abuse

- The childs developmental stage at the time of the abuse

- Duration and frequency of abuse

- Relationship to the perpetrator (bigger effect in a relationship of trust)

- The support the child receives following disclosure (2)

Abuse has long-lasting consequences for a childs physical, emotional and cognitive development and can affect their ability to establish functional relationships with others. As abused children become parents themselves intergenerational transmission of abuse parenting can occur. (2)

Child abuse can also affect society, studies have revealed that three quarters of young criminals in prison have a childhood history of abuse and neglect. (2)

Medical professionals’ responsibilities

Doctors should have a low threshold for suspected child abuse.

What to do if you have concerns:

- Document everything clearly in the patients notes. Clearly attribute who said what/when plus actions taken – including any discussions at handover

- Sign, date and time all entries

- Seek advice from senior colleague/consultant on how to proceed

- If you are unhappy with the advice given consult further – go up a level of seniority or contact the named doctor/nurse for safe guarding.

- Communicate with nursing staff

- Keep the child safe

- DON’T DO NOTHING

Responding to disclosure

- Try not to look shocked

- Let the child know you believe them

- Tell them they are not in trouble

- Listen to what they have to say, don’t make an excuse to leave

- Don’t ask leading questions – this may affect the case if it goes to court

- Don’t make promises you cant keep

- Be honest at all times

- Inform your senior

Why it goes wrong

Despite much being learnt from case reviews and research and current policies constantly being critiqued and updated unfortunately not all incidents can be prevented. There are four areas recognised where professional practice can be improved.

Recognition

Child abuse may go unrecognised if the professional is not looking for it, they lack the clinical skills and experience or it is an unusual presentation.

Communication

Often a number of different professional teams are involved with families where children are at risk. Failure to communicate between the teams is a common reason for why child protection cases are missed or poorly managed. All referrals to a different team regarding child protection concerns must be followed up in writing.

Different teams use different jargon which can further complicate communication. Reports should not contain jargon and test results should be explained.

Procedures

All health professionals working with children should be aware of and adhere to local child protection procedures to ensure children are efficiently and effectively managed.

Note keeping

It is essential all notes are documented correctly – date, time, patient details, clinicians details and clinicians signature should be present on all pages.

Notable cases

Victoria Climbié

Aged 8, Victoria Climbié was taken from the Ivory Coast to live with her Aunt and her partner in London. Within a year Victoria was known to the police, social services, two hospitals the NSPCC and local churches, all of which had noted signs of abuse. All failed to fully investigate or act on their concerns. This failure by multiple agencies over a 10 month period contributed to Victoria’s death on 25 February 2000. Her post mortem recorded 128 separate physical injuries.

Victoria’s aunt and partner were subsequently convicted of murder. A public inquiry, led by Lord Laming, revealed numerous instances where Victoria’s death could have been prevented. The inquiry identified many common themes such as poor communication between professionals, inadequate documentation, an over reliance on others to act, poor protocols and ineffective action once abuse was suspected and inadequate child protection education amongst professionals. (5)

The subsequent report made many recommendations and was the main initiator of the formation of the Every Child Matters Initiative and the introduction of the Children Act 2004 amongst others.

Peter Connelley (Baby P)

Peter Connelley (Baby P) died in 2007 aged 17 months. His body was discovered in a blood stained cot with over severe 50 injuries including a broken back and rib fractures. Peters’ carers were convicted of causing or allowing his death. This tragic death occurred despite Peter being on the Child Protection Register and having been seen 60 times over eight months by police, health professionals and social workers.

An independent review into Peter’s death concluded that child protection services were found to be exceptionally “inadequate” with a further serious case review reporting that child protection staff should have been able to stop the abuse “at the first serious incident”. The death of Peter Connelley sparked major reforms and reviews of child protection procedures in the UK.

The death of baby P attracted considerable media coverage of child protection and social work in England, much of it negative, and some of it targeted individual healthcare workers. Interestingly, when the Sun newspaper published its article ‘Blood on their hands’, it was not referring to those who had caused harm to Peter, but to the professionals, predominantly the social workers involved.

The media attention surrounding this case is considered significant and responsible for what is known as the ‘Baby P effect; – the marked decline in morale and problems in recruiting and retaining staff involved in fronline child protection whilst increasing communication of child protection concerns by the public and partner agencies.

Training courses

All doctors should undertake regular child protection training. All doctors should feel they are competent to recognise and respond to child protection concerns. Doctors should understand their role and in addition have awareness of the roles of the other members of the interdisciplinary team.

The RCPCH has given guidance on available training courses and who should attend them:

| Training programme | Target audience |

| Introduction to safeguarding children and young people

Recognition, Response, Record |

All healthcare professionals (who have contact with children) |

| Child Protection Recognition & Response (CPRR) | Paediatricians in training (ST1-3) and GPs and ED doctors |

| Child Protection in Practice (CPIP) | Paediatricians in training (ST4-7) and GPs and ED doctors |

| Maintaining and updating competences

Child protection: from examination to court Expert witness in child protection: developing excellence |

Paediatric consultant |

(6)

References

| (1) | http://www.rcpch.ac.uk/improving-child-health/child-protection/child-protection |

| (2) | Child protection reader june 2007 RCPCH |

| (3) | http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs150/en/ |

| (4) | Child protection companion 2013. RCPCH. |

| (5) | Yvonne H Carter Lessons from the past, learning for the future: safeguarding children in primary care BJGP 2007; 57 (536): 238-242. |

| (6) | Yvonne H Carter Lessons from the past, learning for the future: safeguarding children in primary care BJGP 2007; 57 (536): 238-242. |

Authors

First draft: Dr Claire Wastakaran

Senior review: Dr Edna Asumang (paediatric consultant) and Dr Louise Ingram (Paediatric speciality registrar)